|

|

||

| Kellscraft

Studio Home Page |

Wallpaper

Images for your Computer |

Nekrassoff Informational Pages |

Web

Text-ures© Free Books on-line |

GULLIVER'S

TRAVELS  By JONATHAN SWIFT  EDITED BY PADRAIC COLUM PRESENTED BY WILLY POGÁNY  I walked about with untmost circumspection, to avoid any stragglers, that might remain on the streets. THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK 1917   THE PUBLISHER TO THE READER

HE

author of these Travels, Mr. Lemuel Gulliver, is my ancient and

intimate friend; there is likewise some relation between us by the

mother's side. About three years ago, Mr. Gulliver growing weary of

the concourse of curious people coming to him at his house in

Redriff, made a small purchase of land, with a convenient house, near

Newark, in Nottinghamshire, his native country; where he now lives

retired, yet in good esteem among his neighbours.

Although Mr. Gulliver was born in Nottinghamshire, where his father dwelt, yet I have heard him say his family came from Oxfordshire; to confirm which, I have observed in the churchyard at Banbury, in that county, several tombs and monuments of the Gullivers. Before he quitted Redriff, he left the custody of the following papers in my hands, with the liberty to dispose of them as I should think fit. I have carefully perused them three times: the style is very plain and simple; and the only fault I find is, that the author, after the manner of travellers, is a little too circumstantial. There is an air of truth apparent through the whole; and indeed the author was so distinguished for his veracity, that it became a sort of proverb among his neighbours at Redriff, when any one affirmed a thing, to say it was as true as if Mr. Gulliver had spoke it. By the advice of several worthy persons, to whom, with the author's permission, I communicated these papers, I now venture to send them into the world, hoping they may be at least, for some time, a better entertainment to our young noblemen, than the common scribbles of politics and party. This volume would have been at least twice as large, if I had not made bold to strike out innumerable passages relating to the winds and tides, as well as to the variations and bearings in the several voyages; together with the minute descriptions of the management of the ship in storms, in the style of sailors: likewise the account of longitudes and latitudes; wherein I have reason to apprehend that Mr. Gulliver may be a little dissatisfied: but I was resolved to fit the work as much as possible to the general capacity of readers. However, if my own ignorance in sea-affairs shall have led me to commit some mistakes, I alone am answerable for them: and if any traveller hath a curiosity to see the whole work at large, as it came from the hand of the author, I will be ready to gratify him. As for any further particulars relating to the author, the reader will receive satisfaction from the first pages of the book. RICHARD SYMPSON.

INTRODUCTION TO "GULLIVER'S TRAVELS" I

He was not Irish either by kin with the Celtic people or the Norman-Irish or the older English colonists. And yet he seems to be Irish by some strange influence. He is Irish by his power of satire and by that reserve that has made the love-interest in his story so puzzling to commentators; he is Irish by his social gift and by his concentrated animosity; he is Irish by his ability for enlisting the populace and of carrying on a propaganda as one might carry on a battle — by horse, foot and artillery. It is noteworthy that the type of literature which we call "Rabelaisian" has, in its better examples, come from the Gaelic frontiers. Sir Thomas Urquhart, a Gael of Scotland, made the grand version of "Pantagruel"; Swift, born and reared in Ireland, wrote "A Tale of a Tub"; Laurence Sterne, born in Ireland too, and of an Irish mother, contributed that changeling's book, "Tristram Shandy." Swift did not like Ireland as a residence, but in Ireland he was looked on as a native, while in England he was a stranger — an Irish condottiere — a "Teague," or, it would be now, a "Paddy" or a "Mick." No doubt it was his national nonconformity rather than his outrageous expression that prevented his reaching the highest political or ecclesiastical preferment. He complains again and again that when it comes to the giving of important employments, the Irish — even the English in Ireland — are always discountenanced. As a man ambitious of the highest place he deplored the fact that he was born an Irishman. But he refused to concede that the English were in any way superior to the people they dominated: the Irish peasantry, "the poor cottagers," had, as he wrote, "much better natural taste for good sense, humour, and raillery than ever I observed amongst the like sort in England." Nor was he misled by the fantastic psychology that is always invented for a subject by an exploiting people. The cause of Irish ruin was for him clearly objective: "Their trade was deliberately crushed purely for the benefit of the English in England," he wrote to Walpole, "all valuable preferences were bestowed upon men born in England as a matter of course, and finally, that in consequence of this the upper classes, deprived of all other openings, were forced to rack-rent their tenants to such a degree that not one farmer in the Kingdom out of a hundred could afford shoes or stockings to his children, or to eat flesh or to drink anything better than sour milk or water twice in a year." Swift, the proudest of men, was a dependent upon others until his thirties. He was educated by the bounty of his uncle; he got a university degree by a back-door and was shipped over to England to get some preferment through his mother's kin; for seven years and again for three years he lived in a great house, partly as a dependent and partly as a secretary; he broke away at the end of seven years to a small rectory, "a hedge-parsonage," he called it, in the north of Ireland; he returned to the great house and was three years more there — this term he was less the dependent and more the secretary. His patron was Sir William Temple, a great and complacent gentleman, who had been a statesman and a diplomat, who now gardened, wrote essays and compiled his memoirs, and was consulted upon occasions by the king and the ministers. Being his assistant was like being in the Foreign Office. Swift had now an apprenticeship in affairs — a less distracted apprenticeship indeed than young diplomats generally get in the regular offices. In his second term with Temple and before his thirties he wrote two extraordinary books, "The Battle of the Books" and "A Tale of a Tub." Dr. Johnson called the last "a wild book." It is a wild book — wild like an unbroken stallion. When Swift left Temple's house he was known to a few as the most powerful writer in English. He was, besides, possibly the best educated young man politically in the British Kingdoms. The proud Roman asked to be first in an Iberian village if he could not be first in Rome. Swift's Iberian village was Larcor in Meath, Ireland. But his fame was growing in the capital. His "Battle of the Books" and his "Tale of a Tub," now published, were acclaimed. He wrote political pamphlets and he headed a mission from the Irish Protestant clergy to the Government in London. His eyes, blue as azure, were somewhat protruding, and were arched by black brows. His face could hold such concentrated rage as to affright the one whom he turned against. His movements were quick and nervous and his bearing was vigorous, for he took much exercise, walking a great deal every day. He was on terms with the common people and he delighted in reproducing their turn of phrase. Altogether he must have appeared as an energetic, commanding and communicable man. But he was afflicted with a dread disease — "labyrinthine vertigo" the physicians have since named it: it gave him frightful pains in the head and these were accompanied by giddiness and fainting-fits. And this malady left a mental shadow — he had a premonition that it would lead to his madness. His mind, he knew, "was a conjured spirit" that would do mischief if he did not give it employment. For "the many thousand wretches" who made up the world he felt hatred and scorn. He spoke of his hate "that on a day" would make "sin and folly bleed," and of his "scorn for fools by fools mistook for pride." Yet he had many friends, and their attachment was a solace to him. There was Esther Johnson, whom he named "Stella." She had been a ward of Sir William Temple, and when Swift had been three years settled in Larcor he invited her and her companion to live near him. Between him and her there was unbroken intimacy and affection. "I knew her," he wrote, "from six years old and had some share in her education by directing what books she should read, and perpetually instructing her in the principles of honour and virtue, from which she never swerved by any one action or moment in her life. She was sick from her childhood until about the age of fifteen; but then grew into perfect health, and was looked upon as one of the most beautiful, graceful and agreeable young women in London. . . . Her hair was blacker than the raven, and every feature in her face perfection." Stella gave her girl's affection and her woman's devotion to Swift, and, as far as we know, she made no demands on him. Very likely it was his malady with its terrible intimations of madness that stood in the way of his marriage with her. For four years — from when he was forty-three to when he was forty-seven — Swift was on the pinnacle of the greatest success. He had as much influence as an important cabinet minister would have now. The patricians who ruled England called him by his Christian name and their ladies had to sing for him when he bade them. He was able to get for his friends the greatest employments, and his influence was such that he could say on behalf of Pope's "Iliad," "the author shall not begin to print till I have a thousand guineas for him." He used his position to advance authors — Pope, Steele, Congreve, Parnell and others less eminent. It seemed part of his pride to make those who were of his own craft honored and secure in their fortune. He came to this position by being the great editorial writer of his day. He was the first writer in English who was able to mould public opinion, — who was able to do in a pamphlet what the greatest orators were able to do in a speech — state a public policy with authority, with invincible logic and in a way that would have popular appeal. He helped to bring a victorious but wearying war to an end and thus made the fortunes of a political party. But his political friends were not eager to make his fortune. There was the embassy to Vienna — Swift did not get it; there was the bishopric in Waterford — it was not given him. Finally he had to make a demand for "something honourable." He was given, not one of the great offices, but a place such as would be given to the well-conducted brother of an heir — the Deanry of St. Patrick's in Dublin. Before he took up his duties there the political party he had helped to raise up was annihilated. After that Swift was a political chief in exile — nay, a political chief banished and proscribed. Tristram had his two Iseults and Swift had his two Esthers. The second was Esther Vanhomrigh, a very independent young woman whom he had met in London in the day of his power. She declared her passion for him and Swift received her declaration with "shame, disappointment, grief and surprise." A man of another nationality might have been more responsive. However, he wrote her a poem "Cadenus and Vanessa," and he tolerated her coming to Ireland. He named her Vanessa. She went to live in a place about twenty miles from Dublin, and with Stella on one side of him and Vanessa on the other the triangle of the dramatists was formed. Swift in Dublin, as we have said, was a political chief in exile, or rather a political chief proscribed. But here he had a second career — a career exciting, tragic and disastrous. He made himself the tribune of the people. First he turned on a government that was about to perpetrate one of the usual jobs on Ireland and he forced it into the position of a tough who had finally to throw up his hands. He organized a boycott against English imports and he wrote powerfully and with ferocious satire on the conditions that were leading to the economic ruin of Ireland. With his intervention in public affairs a new chapter in Irish history begins, and Swift has to be reckoned as the first leader of public opinion in the Ireland that came into being after the destruction of Catholic leadership. He made himself so conspicuously the champion of the Irish people that the Chevalier Wogan — he who carried off the Princess Clementina for a bride for the Pretender — as a representative Irish exile sent him a present of wine and a letter of thanks. He

worked through Gulliver's voyages and he brought the affair of

Vanessa to an end. That misguided lady wrote a letter that was a

demand on Stella to define her relations with him. This drew down on

her a dread visitation. Swift rode to her house, laid down the letter

on a table, looked at her, and departed without saying a word. One

might say that the encounter turned the current of Vanessa's life.

She died soon after. Swift might hold himself blameless, but he must

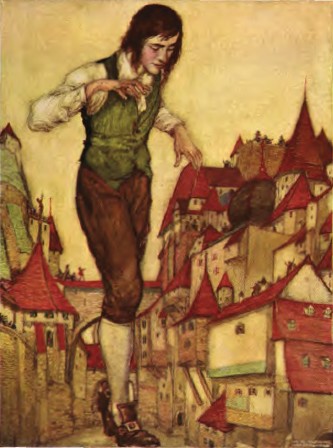

have been made to realize And matter enough to save one's own. Some portion of remorse must have been added to his other afflictions. The writing of "Gulliver" still went on. But now Stella became ill and her illness became threatening. Swift was affrighted into cowardice. She died and he was left with nothing but the indignation that his epitaph commemorates — the indignation that lacerated his heart, the indignation that ate his flesh and exhausted his spirit. In "Gulliver's Travels" we can see the progress of this destructive force. A year after Stella's death the book was published. Ten years later the shadows closed around Swift's mind and the day came when he said "I am mad." In the last episodes of Gulliver, as in the last stories of Mau-passant and the last rhapsodies of Nietzsche, we are oppressed by the shadow of intellectual ruin. II Just as the man of to-day has to refer to many inventions, so the writer of to-day has to refer to many ideas. It was not so with the older writers: they referred to few ideas and they were able to spend all their power in illustrating them. The modern writers have abundance in idea, whereas the older writers had abundance in power. This difference is very notably shown by "Gulliver's Travels." It is all an illustration of one idea firmly held: Swift looks from above down upon men; he looks from below up at them, and then he looks at them from behind. He breaks into no complexity of idea. But he puts so much power into his statement that we know as much about the Lilliputians and the Brobdingnagians and the Houyhnhnms as if we had read our twelve volumes on each by the Gibbon of their respective empires. In each of the four voyages there is satire in the formal sense — particular institutions and policies, special crimes and vices are exposed to our mockery and our disgust. But these exposures are only side-attacks: the satire is in the world which Swift creates over against our own — a world in which there is no place for our affection; by creating such a world he has made a great general satire. He creates this world most triumphantly when he alters the measurement of man; he creates it most horribly when he gives beasts the reason of men and gives men the habits of beasts; he creates it again when he makes human reason occupy itself solely with frivolous things. This world in which there is no place for our affection is in itself a satire upon our world, the atmosphere of which is human affection. We can feel no affection for beings so small that they would be infants to our infants, and so large that they would be higher than our houses; so pedantic that they would weary our reason and so foul that we should shrink away from them. No one has created more triumphantly this world without atmosphere — this world in which there is nothing between us and the peoples' functions. But if there is no place for our affection in such a world, there is all the more place for our wonder. Here is the world of the little, reasonably arranged for us, and as we go through it we feel the same wonder as at the egg of the hummingbird; here is the world of the big, also reasonably arranged, and as we go through it we feel the same wonder as at the egg of the ostrich; here is the flying island, and here are the beasts that conduct themselves with the reasonableness of men. It is a wonder-tale such as Julius Cćsar would have recounted — ordered, informing, literal. It has the general's or the statesman's or the historian's sense of fact. If the Lilliputians measure up to humanity inch for foot and if the Brobdingnagians tower above them foot for inch, everything in their respective countries—trees, crops, animals, temples, ships —are exactly to scale. Only once do his enemies, the mathematicians, find Swift out in his reckoning. It is when he describes Gulliver drawing the fleet of the Blefuscians into the Lilliputian harbor. He draws fifty ships by their cables "with great ease." The author supposes, notes Professor De Morgan, that a man up to his neck in water could drag by a rope a mass equal to 50/1728 of a line of battle ship of his own time — "or put it thus: the 30,000 men who jumped out of their ships would amount in weight and bulk to a little more than seventeen men of our size. Could a man up to his neck in water drag (‘with great ease') the boat which would hold seventeen men not closely packed? Probably not; and still less could Gulliver have dragged the ships." But we feel more inclined to take Gulliver's word for it than to accept the mathematician's demonstration. "Gulliver's Travels" is a fairy tale inverted. In the fairy tale the little beings have beauty and graciousness, the giants are dull-witted, and the beasts are helpful, and humanity is shown as triumphant. In "Gulliver" the little beings are hurtful, the giants have more insight than men, the beasts rule, and humanity is shown, not as triumphant, but as degraded and enslaved. The third voyage — the one to Laputa — is outside the simple formula that is suggested by our most vivid recollection of "Gulliver" — the formula of looking down at humanity, of looking up at humanity and of looking at humanity from the other side; it differs from the other voyages too in being, not a narrative but a series of satirical studies. Gulliver ceases to be a hero and becomes a bystander. In Swift's own day it was doubted that the voyage to Laputa was by the same hand as wrote the voyages to Lilliputia, to Brobdingnagia and to the country of the Houyhnhnms. But who else could have written the account of the Academy of Projectors and the description of the Struldbrugs? This particular voyage belongs to Gulliver's travels only because Swift tells us that the surgeon-captain went to and came back from such places — that is to say, only by the opening and closing passages. But it is wonderful writing, and just because it is a series of studies rather than a regular narrative, it makes relief between the first two and the fourth voyage. Because "Gulliver's Travels" seems to belong to an older era in literature it is well to remind ourselves that it was written after "Robinson Crusoe." Swift need not have owed anything of his literal and exact style to Defoe — he was literal in his verse and literal in his jokes. Both he and the author of "Robinson Crusoe" modelled their imaginary voyages on the accounts of real voyages written by English seamen — even by just such seamen as the surgeon-captain, Lemuel Gulliver — men who could have invented nothing and who made even the discoveries of Australia and the paradisal islands of the South Seas as unimaginative as a volume of sermons by the ship's chaplain. Swift brings to the composition of his imaginary voyages an inspired literalness. What could be more authentic and at the same time be more of a literary discovery than his names, geographical and personal? Robinson Crusoe is a good name, but it is a name that the ship-chandler might invent. But think of Lemuel Gulliver! It is the name of a traveller, but not quite a prosaic traveller — a traveller born under some credulous star. It is not, however, the name of the voyager to Laputa. The stranger there was so much of a worldling as to be able to take the attitude of a bystander. Captain Gulliver was too simple a man to take such clever stock of the Academicians and the Projectors. Swift had his own secret "little language" from which he derived words and names. Lilliputian, Brobdingnagian, Houyhnhnm, Yahoo are words permanently added to the language of mankind. Only Swift, the man who invented riddles, made puns and concocted secret languages, could have discovered them. And the words he gives from the Lilliputian and Brobdingnagian and Houyhnhnm are in perfect keeping with our ideas of the speakers. We could lisp in Lilliputian but we would neigh in Houyhnhnm, and we should need superhuman speech-organs to pronounce the Brobdingnagian consonants. The voyager presents us with only a few words from each language, but back of these words there seems to be an intellectual history. One feels that philologists might reconstruct whole languages from them. No book in the history of literature has had such good fortune as "Gulliver's Travels." It has gone into the world and the world has received it as its own, and it has gone into the nursery and the nursery has given it the immortality of "Jack and the Beanstalk." It has been read by children as a wonder-tale and by statesmen in exile as a piece of secret history. Here the "Travels of Lemuel Gulliver into remote Nations of the World" are presented, not for their worldliness, but for their wonder. The voyages have been made over, as often before, into a story for children. For them Gulliver will bestride a country, and will walk through streets taking care that his clothes do not brush down the houses; he will be put into a giant's pocket, and will be carried away, house and all, in an eagle's beak; he will come to the flying island, and afterwards will be spoken to by the wise horses. And, until they are as old as she was, the folk who read it need not understand what Sara, Duchess of Marlborough meant when she said "Tell him it is the most accurate account of Kings, ministers, bishops and courts of justice that it is possible to be writ." PADRAIC

COLUM.

PART I A VOYAGE TO LILLIPUT CHAP. I. The Author gives some account of himself and family, his first inducements to travel. He is shipwrecked, and swims for his life, gets safe on shore in the country of Lilliput, is made a prisoner, and carried up the country CHAP. II. The Emperor of Lilliput, attended by several of the nobility, comes to see the Author in his confinement. The Emperor's person and habit described. Learned men appointed to teach the Author their language. He gains favour by his mild disposition. His pockets are searched, and his sword and pistols taken from him CHAP. III. The Author diverts the Emperor, and his nobility of both sexes, in a very uncommon manner. The diversions of the court of Lilliput described. The Author has his liberty granted him upon certain conditions CHAP. IV. Mildendo, the metropolis of Lilliput, described, together with the Emperor's palace. A conversation between the Author and a principal secretary, concerning the affairs of that empire. The Author's offers to serve the Emperor in his wars CHAP. V. The Author, by an extraordinary stratagem, prevents an invasion. A high title of honour is conferred upon him. Ambassadors arrive front the Emperor of Blefuscu, and sue for peace CHAP. VI. Of the inhabitants of Lilliput; their learning, laws, and customs, the manner of educating their children. The Author's way of living in that country. His vindication of a great lady CHAP. VII. The Author, being informed of a design to accuse him of high-treason, makes his escape to Blefuscu. His reception there CHAP. VIII. The Author, by a lucky accident, finds means to leave Blefuscu; and, after some difficulties, returns safe to his native country

A VOYAGE TO BROBDINGNAG CHAP. I. A great storm described, the long-boat sent to fetch water, the Author goes with it to discover the country. He is left on shore, is seized by one of the natives, and carried to a farmer's house. His reception there with several accidents that happened there. A description of the inhabitants CHAP. II. A description of the farmer's daughter. The Author carried to a market-town, and then to the metropolis. The particulars of his journey CHAP. III. The Author sent for to court. The Queen buys him of his master the farmer, and presents him to the King. He disputes with his majesty's great scholars. An apartment at court provided for the Author. He is in high favour with the Queen. He stands up for the honour of his own country. His quarrels with the Queen's dwarf CHAP. IV. The country described. A proposal for correcting modern maps. The King's palace, and some account of the metropolis. The Author's, way of travelling. The chief temple described CHAP. V. Several adventures that happened to the Author. The Author shows his skill in navigation CHAP. VI. Several contrivances of the Author to please the King and Queen. He skews his skill in music. The King inquires into the state of Europe, which the Author relates to him. The King's observations thereon CHAP. VII. The Author's love of his country. He makes a proposal of much advantage to the King, which is rejected. The King's great ignorance in politics. The learning of that country very imperfect and confined. The laws, and military affairs, and parties in the state CHAP. VIII. The King and Queen make a progress to the frontiers. The Author attends them. The manner in which he leaves the country very particularly related. He returns to England

A VOYAGE TO LAPUTA, BALNIBARBI, LUGGNAGG, GLUBBDUBDRIB, AND JAPAN CHAP. I. The Author sets out on his third voyage, is taken by pirates. The malice of a Dutchman. His arrival at an island. He is received into Laputa CHAP. II. The humours and dispositions of the Laputians described. An account of their learning. Of the King and his court. The Author's reception there. The inhabitants subject to fear and disquietudes CHAP. III. A phenomenon solved by modern philosophy and astronomy. The Laputians' great improvements in the latter. The King's method of suppressing insurrections CHAP. IV. The Author leaves Laputa; is conveyed to Balnibarbi, arrives at the metropolis. A description of the metropolis, and the country adjoining. The Author hospitably received by a great Lord. His conversation with that Lord CHAP. V. The Author permitted to see the Grand Academy of Lagado. The Academy largely described. The Arts wherein the professors employ themselves CHAP. VI. The Author leaves Lagado, arrives at Maldonada. No ship ready. He takes a short voyage to Glubbdubdrib. His reception by the Governor CHAP. VII. The Luggnaggians commended. A particular description of the Struldbrugs, with many conversations between the Author and some eminent persons upon that subject CHAP. VIII. The Author leaves Luggnagg, and sails to Japan. From thence he returns in a Dutch ship to Amsterdam, and from Amsterdam to England

A VOYAGE TO THE COUNTRY OF THE HOUYHNHNMS CHAP. I. The Author sets out as Captain of a ship. His men conspire against him, confine him a long time to his cabin, set him on shore in an unknown land. He travels up into the country. The Yahoos, a strange sort of animal, described. The Author meets two Houyhnhnms CHAP. II. The Author conducted by a Houyhnhnm to his house. The house described. The Author's reception. The food of the Houyhnhnms. The Author in distress for want of meat, is at last relieved. His manner of feeding in this country CHAP. III. The Author studious to learn the language, the Houyhnhnm his master assists in teaching him. The language described. Several Houyhnhnms of quality come out of curiosity to see the Author. He gives his master a short account of his voyage CHAP. IV. The Houyhnhnm’s notion of truth and falsehood. The Author's discourse disapproved by his master. The Author gives a more particular account of himself, and the accidents of his voyage CHAP. V. The Author, at his master's commands, informs him of the state of England. The causes of war among the princes of Europe. The Author begins to explain the English constitution CHAP. VI. The great virtues of the Houyhnhnms. The education and exercise of their youth. Their general assembly. Their learning. Their buildings. Their manner of burials. The defectiveness of their language CHAP. VII. The Author's economy, and happy life, among the Houyhnhnms. His great improvement in virtue by conversing with them. Their conversations. The Author has notice given him by his master, that he must depart from the country. He falls into a swoon for grief, but submits. He contrives and finishes a canoe, by the kelp of a fellow-servant, and puts to sea at a venture CHAP. VIII. The Author's dangerous voyage. He arrives at New Holland, hoping to settle there. Is wounded with an arrow by one of the natives. Is seized and carried by force into a Portuguese ship. The great civilities of the Captain. The Author arrives at England CHAP. IX. The Author's veracity. His design, in publishing his work. His censure of those travellers who swerve from the truth. The Author clears himself from any sinister ends in writing. An objection answered. The method of planting colonies. His native country commended. The right of the Crown to those countries described by the Author, is justified. The difficulty of conquering them. The Author takes his last leave of the reader; proposeth his manner of living for the future, gives good advice, and concludes

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

I

walked with the utmost circumspection, to avoid treading on any

stragglers, that might remain in the streets

His Excellency, having mounted on the small of my right leg, advanced forwards up to my face, with about a dozen of his retinue The Emperor holds a stick in his hands while the candidates sometimes leap over the stick, sometimes creep under it backwards and forwards several times, according as the stick is advanced or depressed They perceived the whole fleet moving in order and saw me pulling at the end The farmer took a piece of a small straw and therewith lifted up the lappets of my coat She was likewise my school-mistress; when I pointed to anything she told me the name of it in her own tongue, so that in a few days I was able to call for whatever I had a mind to The monkey was seen by hundreds in the court, sitting upon the ridge of a building, holding me like a baby in one of his fore-paws Some eagle had got the ring of my box in his beak, with an intent to let it fall on a rock like a tortoise in a shell, and then pick out my body and devour it His Majesty took not the least notice of us — he was then deep in a problem Their employment was to mix colours for painters which their master taught them to distinguish by feeling and smelling I ran to the body of a tree, and leaning my back against it, kept them off by waving my hanger I was going to prostrate myself to kiss his hoof, he did me the honour to raise it gently to my mouth |