|

|

||

| Kellscraft

Studio Home Page |

Wallpaper

Images for your Computer |

Nekrassoff Informational Pages |

Web

Text-uresę Free Books on-line |

| Order

A Print Copy Here |

THE

ART AND CRAFT OF PRINTING

BY

WILLIAM MORRIS.

A NOTE

BY WILLIAM MORRIS ON HIS AIMS IN FOUNDING THE KELMSCOTT PRESS, TOGETHER

WITH A SHORT DESCRIPTION OF THE PRESS BY S. C. COCKERELL, AND AN

ANNOTATED LIST

OF THE BOOKS PRINTED THEREAT.

1902

A SHORT HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION OF THE KELMSCOTT PRESS.

AN ANNOTATED LIST OF ALL THE BOOKS PRINTED AT THE KELMSCOTT PRESS

IN THE ORDER IN WHICH THEY WERE ISSUED.

VARIOUS LISTS, LEAFLETS AND ANNOUNCEMENTS PRINTED AT THE KELMSCOTT PRESS.

THE IDEAL BOOK: AN ADDRESS BY WILLIAM MORRIS,

DELIVERED BEFORE THE BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON, MDCCCXCIII.

AN ESSAY ON PRINTING, BY WILLIAM MORRIS AND EMERY WALKER,

FROM ARTS AND CRAFTS ESSAYS

BY MEMBERS OF THE ARTS AND CRAFTS EXHIBITION SOCIETY.tHE

NOTE TO THE PRESENT EDITION

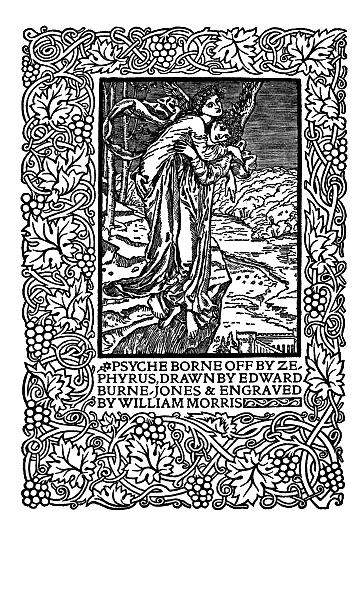

PSYCHE BORNE OFF BY ZEPHYRUS, DRAWN BY EDWARD BURNE-JONES & ENGRAVED BY WILLIAM MORRIS

began

printing books with the hope

of producing some

which would have a

definite

claim to beauty,

while at the

same time

they should be easy to

read and should not dazzle the eye, or trouble the intellect of the

reader by

eccentricity of form in the letters. I have always been a great admirer

of the

calligraphy of the Middle Ages, & of the earlier printing which

took its

place. As to the fifteenth-century books, I had noticed that they were

always

beautiful by force of the mere typography, even without the added

ornament,

with which many of them are so lavishly supplied. And it was the

essence of my

undertaking to produce books which it would be a pleasure to look upon

as

pieces of printing and arrangement

of type. Looking

at my adventure from this point of view then, I found I had to consider

chiefly

the following things: the paper, the form of the type, the relative

spacing of

the letters, the words, and the lines; and lastly the position of the

printed

matter on the page. It was a matter of course that I should consider it

necessary that the paper should be hand-made, both for the sake of

durability

and appearance. It would be a very false economy to stint in the

quality of the

paper as to price: so I had only to think about the kind of hand-made

paper. On

this head I came to two conclusions: 1st, that the paper must be wholly

of

linen (most hand-made papers are of cotton today), and must be quite

'hard,' i.

e., thoroughly well sized; and 2nd, that, though it must be 'laid' and

not

'wove' (i. e., made on a mould made of obvious wires), the lines caused

by the

wires of the mould must not be too strong, so as to give a ribbed

appearance. I

found that on these points I was at one with the practice of the

paper-makers

of the fifteenth century; so I took as my model a Bolognese paper of

about

1473. My friend Mr. Batchelor, of Little Chart, Kent, carried out my

views very

satisfactorily, and produced from the first the excellent paper, which

I still

use.

Next

as to type. By instinct rather than by conscious thinking it over,

I began by getting myself a fount of Roman type. And here what I wanted

was

letter pure in form; severe, without needless excrescences; solid,

without the

thickening and thinning of the line, which is the essential fault of

the

ordinary modern type, and which makes it difficult to read; and not

compressed

laterally, as all later type has grown to be owing to commercial

exigencies.

There was only one source from which to take examples of this perfected

Roman type,

to wit, the works of the great Venetian printers of the fifteenth

century, of

whom Nicholas Jenson produced the completest and most Roman characters

from

1470 to 1476. This type I studied with much care, getting it

photographed to a

big scale, and drawing it over many times before I began designing my

own

letter; so that though I think I mastered the essence of it, I did not

copy it

servilely; in fact, my Roman type, especially in the lower case, tends

rather

more to the Gothic than does Jenson's.

After

a while I felt that I must have a Gothic as well as a Roman fount;

and herein the task I set myself was to redeem the Gothic character

from the

charge of unreadableness which is commonly brought against it. And I

felt that

this charge could not be reasonably brought against the types of the

first two

decades of printing: that Schoeffer at Mainz, Mentelin at Strasburg,

and

Gunther Zainer at Augsburg, avoided the spiky ends and undue

compression which

lay some of the later type open to the above charge. Only the earlier

printers (naturally

following therein the practice of their predecessors the scribes) were

very

liberal of contractions, and used an excess of 'tied' letters, which,

by the

way, are very useful to the compositor. So I entirely eschewed

contractions,

except for the '&,' and had very few tied letters, in fact none

but the

absolutely necessary ones. Keeping my end steadily in view, I designed

a

black-letter type which I think I may claim to be as readable as a

Roman one,

and to say the truth I prefer it to the Roman. This type is of the size

called Great

Primer (the Roman type is of 'English' size); but later on I was driven

by the

necessities of the Chaucer (a double-columned book) to get a smaller

Gothic

type of Pica size.

The

punches for all these types, I may mention, were cut for me with

great intelligence and skill by Mr. E. P. Prince, and render my designs

most

satisfactorily.

Now as

to the spacing: First, the 'face' of the letter should be as

nearly conterminous with the 'body' as possible, so as to avoid undue

whites

between the letters. Next, the lateral spaces between the words should

be (a)

no more than is necessary to distinguish clearly the division into

words, and

(b) should be as nearly equal as possible. Modern printers, even the

best, pay

very little heed to these two essentials of seemly composition, and the

inferior ones run riot in licentious spacing, thereby producing, inter

alia,

those ugly rivers of lines running about the page which are such a

blemish to

decent printing. Third, the whites between the lines should not be

excessive;

the modern practice of 'leading' should be used as little as possible,

and

never without some definite reason, such as marking some special piece

of

printing. The only leading I have allowed myself is in some cases a

'thin' lead

between the lines of my Gothic pica type: in the Chaucer and the

double-columned books I have used a 'hair' lead, and not even this in

the 16mo

books. Lastly, but by no means least, comes the position of the printed

matter

on the page. This should always leave the inner margin the narrowest,

the top somewhat

wider, the outside (fore-edge) wider still, and the bottom widest of

all. This

rule is never departed from in mediŠval books, written or printed.

Modern

printers systematically transgress against it; thus apparently

contradicting

the fact that the unit of a book is not one page, but a pair of pages.

A

friend, the librarian of one of our most important private libraries,

tells me

that after careful testing he has come to the conclusion that the

mediŠval rule

was to make a difference of 20 per cent. from margin to margin. Now

these matters

of spacing and position are of the greatest importance in the

production of

beautiful books; if they are properly considered they will make a book

printed

in quite ordinary type at least decent and pleasant to the eye. The

disregard

of them will spoil the effect of the best designed type.

It was

only natural that I, a decorator by profession, should attempt to

ornament my books suitably: about this matter, I will only say that I

have

always tried to keep in mind the necessity for making my decoration a

part of

the page of type. I may add that in designing the magnificent and

inimitable

woodcuts which have adorned several of my books, and will above all

adorn the

Chaucer which is now drawing near completion, my friend Sir Edward

Burne-Jones

has never lost sight of this important point, so that his work will not

only

give us a series of most beautiful and imaginative pictures, but form

the most

harmonious decoration possible to the printed book.

Upper Mall, Hammersmith.

Nov. 11, 1895