| 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Beasts of the Field Content Page |

(HOME) |

| 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Beasts of the Field Content Page |

(HOME) |

THERE is a curious Indian legend about Meeko the red squirrel — the Mischief-Maker, as the Milicetes call him — which is also an excellent commentary upon his character. Simmo told it to me one day when we had caught Meeko coming out of a woodpecker’s hole with the last of a brood of fledgelings in his mouth, chuckling to himself over his hunting. Long ago, in the days when Clote Scarpe ruled the animals, Meeko was much larger than he is now, large as Mooween the bear. But his temper was so fierce and his disposition so altogether bad that the wood folk were threatened with destruction.. Meeko killed right and left with the temper of a weasel, who kills from pure lust of blood. So Clote Scarpe, to save the little woods-people, made Meeko smaller — small as he is now. Unfortunately, Clote Scarpe forgot Meeko’s disposition, which remained as big and as bad as before. So now Meeko goes about the woods with a small body and a great temper, barking, scolding, quarreling and, since he cannot destroy in his rage as before, setting other animals by the ears to destroy each other. When you have listened to Meeko’s scolding for a season, and have seen him going from nest to nest after innocent fledgelings; or creeping into the den of his big cousin, the beautiful gray squirrel, to kill the young; or driving away his little cousin, the chipmunk, to steal his hoarded nuts; or watching every fight that goes on in the woods, jeering and chuckling above it,— then you begin to understand the Indian legend. Spite of his doubtful ways, however, he is interesting and always unexpected. When you have watched the red squirrel that lives near your camp all summer, feeding from your hand and sharing your life until you think you know all about him, he does the queerest thing, good or bad, to upset all your theories and cast the shadow of doubt upon the Indian legends about him. I remember one squirrel that greeted me, the first living thing in the great woods, as I ran my canoe ashore on a wilderness river. Meeko heard me coming. His bark sounded loudly in a big spruce above the dip of the paddles. As we turned shoreward, he ran down the tree in which he was, and out on a fallen log to meet us. I grasped a branch of the old log to steady the canoe and watched him curiously. He had never seen a man before; he barked, jeered, scolded, jerked his tail, whistled, did everything within his power to make me show my teeth and my disposition. Suddenly

he grew excited — and when Meeko grows excited the woods are

not big enough to

hold him. He came nearer and nearer to my canoe, till

he leaped upon the gunwale

and sat there chattering, as if he were Adjidaumo come back

again and I were

Hiawatha. All the while he had poured out a torrent

of squirrel talk, but now

his note changed; jeering and scolding and curiosity went out

of it; something

else crept in. I began to feel, somehow, that he was trying

to make me

understand something, and found me very stupid about it.

I

began to talk quietly, calling him a rattle-head and a disturber of the

peace. At the

first sound of my voice he listened with intense curiosity, then leaped

to the log, ran the length of it, jumped down and began to dig

furiously among

the moss and dead leaves. Every moment or two he would stop,

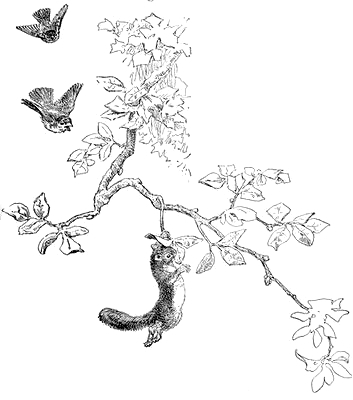

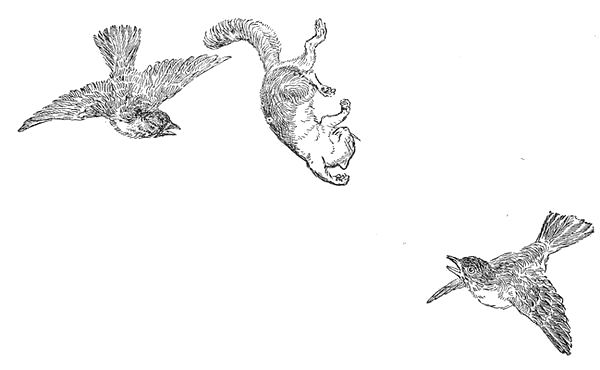

and jump to the Presently he ran to my canoe, sprang upon the gunwale, jumped back again, and ran along the log as before to where he had been digging. He did it again, looking back at me and saying plainly: “Come here, come and look.” I stepped out of the canoe to the old log, whereupon Meeko went off into a fit of terrible excitement. — I was bigger than he expected; I had only two legs; kut-e-k’ chuck, kut-e-k’chuck! whit, whit, whit, kut-e-k’ chuck! I stood where I was until he got over his excitement. Then he came towards me, and led me along the log, with much chuckling and jabbering, to the hole in the leaves where he had been digging. When I bent over it he sprang to a spruce trunk, on a level with my head, fairly bursting with excitement, but watching me with intensest interest. In the hole I found a small lizard, one of the rare kind that lives under logs and loves the dusk. He had been bitten through the back and disabled. He could still use legs, tail, and head feebly, but could not run away. When I picked him up and held him in my hand, Meeko came closer with loud-voiced curiosity, longing to leap to my hand and claim his own, but held back by fear.— “What is it? He’s mine; I found him. What is it?” he barked, jumping about as if bewitched. Two curiosities, the lizard and the man, were almost too much for him. I never saw a squirrel more excited. He had evidently found the lizard by accident, bit him to keep him still, and then, astonished by the rare find, hid him away where he could dig him out and watch him at leisure. I put the lizard back into the hole and covered him with leaves; then went to unloading my canoe. Meeko watched me closely. The moment I was gone he dug away the leaves, took his treasure out, watched it with wide bright eyes, bit it once more to keep it still, and covered it up again carefully. Then he came chuckling along to where I was putting up my tent. In a week he owned the camp, coming and going at his own will, stealing my provisions when I forgot to feed him, and scolding me roundly at every irregular occurrence. He was an early riser and insisted on my conforming to the custom. Every morning at daylight, he would leap from a fir tip to my ridge-pole, and sit there, barking and whistling, until I put my head out of my door, or until Simmo came along with his axe. Of Simmo and his axe Meeko had a mortal dread, which I could not understand till one day when I paddled silently back to camp and, instead of coming up the path, sat idly in my canoe watching the Indian, who had broken his one pipe and now sat making another out of a chunk of black alder and a length of nanny bush. Simmo was as interesting to watch, in his way, as any of the wood folk. Presently Meeko came down, chattering his curiosity at seeing the Indian, so still and so occupied. A red squirrel is always unhappy unless he knows all about everything. He watched from the nearest tree for a while, but could not make up his mind what was going on. Then he came down to the ground and advanced a foot at a time, jumping up continually but coming down in the same spot, barking to make Simmo turn his head and show his hand. Simmo watched out of the corner of his eye until Meeko was near a solitary tree which stood in the middle of the camp ground, when he jumped up suddenly and rushed at the squirrel, who sprang to the tree and ran to a branch out of reach, snickering and jeering. Simmo took his axe deliberately and swung it mightily at the foot of the tree, as if to chop it down; only he hit the trunk with the head, not the blade of his weapon. At the first blow, which made his toes tingle, Meeko stopped jeering and ran higher. Simmo swung again and Meeko went up another notch. So it went on, Simmo looking up intently to see the effect and Meeko running higher after each blow, until the tip-top was reached. Then Simmo gave a mighty whack; the squirrel leaped far out and came to the ground, sixty feet below; picked himself up, none the worse for his leap, and rushed scolding away to his nest. Then Simmo said umpfh! like a bear, and went back to his pipe-making. He had not smiled nor relaxed the intent expression of his face during the whole little comedy. I found out afterwards that making Meeko jump from a tree-top is one of the few diversions of Indian children. I tried it myself many times with many squirrels, and found my astonishment that a jump from any height, however great, is no concern to a squirrel, red or gray. They have a way of flattening the whole body and tail against the air, which breaks their fall. Their bodies, and especially their bushy tails, have a curious tremulous motion, like the quiver of wings, as they come down. The flying squirrel’s sailing down from a tree-top to another tree, fifty feet away, is but an exaggeration, due to the membrane connecting the fore and hind legs, of what all squirrels’ practice continually. I have seen a red squirrel land lightly after jumping from an enormous height, and run away as if nothing unusual had happened. But though I have watched them often, I have never seen a squirrel do this except when compelled to do so. When chased by a weasel or a marten, or when the axe beats against the trunk below — either because the vibration hurts their feet, or else they fear the tree is being cut down — they use the strange gift to save their lives. But I fancy it is a breathless experience, and they never try it for fun; though I have seen them do all sorts of risky stumps in leaping from branch to branch. It would be interesting to know whether the raccoon also, a large, heavy animal, has the same way of breaking his fall when he jumps from a height. One bright moonlight night, when I ran ahead of the dogs, I saw a big coon leap from a tree to the ground, a distance of some thirty or forty feet. The dogs had treed him in an evergreen, and he left them howling below while he stole silently from branch to branch until a good distance away, when, to save time, he leaped to the ground. He struck with a heavy thump, but ran on uninjured as swiftly as before, and gave the dogs a long run before they treed him again. The sole of a coon’s foot is so padded with fat and gristle that it touches the ground like a coiled spring. This helps him greatly in his dizzy jumps; but I suspect that he also knows the squirrel trick of flattening his body and tail against the air so as to fall lightly. The chipmunk seems to be the only one of the squirrel family in whom this gift is wanting. Possibly be has it also, if the need ever comes. I fancy, however, that he would fare badly if compelled to jump from a spruce top, for his body is heavy and his tail small from long living on the ground; all of which seems to indicate that the tree squirrel’s bushy tail is given him, not for ornament, but to aid his passage from branch to branch, and to break his fall when he comes down from a height. By way of contrast with Meeko, you may try a curious trick on the chipmunk. It is not easy to get him into a tree; he prefers a log or an old wall when frightened; and he is seldom more than two or three jumps from his den. But watch him as he goes from his garner to the grove where the acorns are, or to the field where his winter corn is ripening. Put yourself near his path (he always follows the same one to and fro) where there is no refuge close at hand. Then, as he comes along, rush at him suddenly and he will take to the nearest tree in his alarm. When he recovers from his fright — which is soon over; for he is the most trustful of squirrels and looks down at you with interest, never questioning your motives — take a stick and begin to tap the tree softly. The more slow and rhythmical your tattoo the sooner he is charmed. Presently he comes down closer and closer, his eyes filled with strange wonder. More than once I have had a chipmunk come to my hand and rest upon it, looking everywhere for the queer sound that brought him down, forgetting fright and cornfield and coming winter in his bright curiosity.  Meeko is a bird of another color. He never trusts you nor anybody else fully, and his curiosity is generally of the vulgar, selfish kind. When the autumn woods are busy places, and wings flutter and little feet go pattering everywhere after winter supplies, he also begins garnering, remembering the hungry days of last winter. But he is always more curious to see what others are doing than to fill his own bins He seldom trusts to one storehouse — he is too suspicious for that — but hides his things in twenty different places; some shagbarks in the old wall, a handful of acorns in a hollow tree, an ear of corn under the eaves of the old barn, a pint of chestnuts scattered about in the trees, some in crevices in the bark, some in a pine crotch covered carefully with needles, and one or two stuck firmly into the splinters of every broken branch that is not too conspicuous. But he never gathers much at a time. The moment he sees anybody else gathering he forgets his own work and goes spying to see where others are hiding their store. The little chipmunk, who knows his thieving and his devices, always makes one turn, at least, in the tunnel to his den too small for Meeko to follow. He sees a blue jay flitting through the woods, and knows by his unusual silence that he is hiding things. Meeko follows after him, stopping all his jabber and stealing from tree to tree, watching, for hours if need be, until he knows that Deedeeaskh is gathering corn from a certain field. Then he watches the line of flight, like a bee hunter, and sees Deedeeaskh disappear twice by an oak on the wood’s edge. Meeko rushes away at a headlong pace and hides himself in the oak. There he traces the jay’s line of flight a little farther into the woods; sees the unconscious thief disappear by an old pine. Meeko hides in the pine, and so traces the jay straight to one of his storehouses. Sometimes Meeko is so elated over the discovery that, with all the fields laden with food, he cannot wait for winter. When the jay goes away Meeko falls to eating or to carrying away his store. More often he marks the spot and goes away silently. When he is hungry he will carry off Deedeeaskh’s corn before touching his own. Once I saw the tables turned in a most interesting fashion. Deedeeaskh is as big a thief in his way as is Meeko, and also as vile a nest-robber. The red squirrel had found a hoard of chestnuts — small fruit, but sweet and good — and was hiding it away. Part of it he stored in a hollow under the stub of a broken branch, twenty feet from the ground, so near the source of supply that no one would ever think of looking for it there. While he was gone back to his chestnut tree, and I watched for his return, a blue jay came stealing into the tree, spying and sneaking about as if a nest of fresh thrush’s eggs were somewhere near. He smelled a mouse evidently, for after a moment’s spying he hid himself away in the tree-top, close up against the trunk. Presently Meeko came back, with his face bulging as if he had toothache, uncovered his store, emptied in the half-dozen chestnuts from his cheek pockets and covered them all up again. The moment he was gone the blue jay went straight to the spot, seized a mouthful of nuts, and flew swiftly away. He made three trips before the squirrel came back. Meeko in his hurry never noticed the loss, but emptied his pockets and was off to the chestnut tree again. When he returned, the jay in his eagerness had disturbed the leaves which covered the hidden store. Meeko noticed it and was all suspicion in an instant. He whipped off the covering and stood staring down intently into the garner, evidently trying to compute the number he had brought and the number that were there. Then a terrible scolding began, a scolding that was broken short off when a distant screaming of jays came floating through the woods. Meeko covered his store hurriedly, ran along a limb and leaped to the next tree, where he hid in a knot hole, just his eyes visible, watching his garner keenly out of the darkness. Meeko has no patience. Three or four times he showed himself nervously. Fortunately for me, the jay had found some excitement to keep his rattle-brain busy for a moment. A flash of blue, and he came stealing back, just as Meeko had settled himself for more watching. After much peeking and listening the jay flew down to the storehouse, and Meeko, unable to contain himself a moment longer at sight of the thief, jumped out of his hiding and came rushing along the limb, hurling threats and vituperation ahead of him. The jay fluttered off, screaming derision. Meeko followed, hurling more abuse, but soon gave up the chase and came back to his chestnuts. It was curious to watch him there, sitting motionless and intent, his nose close down to his treasure, trying to compute his loss. Then he stuffed his cheeks full and began carrying his hoard off to another hiding place. HURLING

THREATS AND VITUPERATION AHEAD OF HIM

The autumn woods are full of such little comedies. Jays, crows, and squirrels are all hiding away winter’s supplies, and no matter how great the abundance, not one of them can resist the temptation to steal or to break into another’s garner. Meeko is a poor provider; he would much rather live on buds and bark and apple seeds and fir cones, and what he can steal from others in the winter, than bother himself with laying up supplies of his own. When the spring comes he goes a-hunting and is for a season the most villainous of nest robbers. Every bird in the woods then hates him, takes a jab at him, and cries thief! thief! wherever he goes. On a trout brook, once, I had a curious sense of comradeship with Meeko. It was in the early spring, when all the wild things make holiday, and man goes a-fishing. Near the brook a red squirrel had tapped a maple tree with his teeth and was tasting the sweet sap as it came up scantily. Seeing him and remembering my own boyhood, I cut a little hollow into the bark of a black birch tree and, when it brimmed full, drank the sap with immense satisfaction. Meeko stopped his own drinking to watch, then to scold and denounce me roundly. While my cup was filling again I went down to the brook and took a wary old trout from his den under the end of a log, where the foam bubbles were dancing merrily. When I went back, thirsting for another sweet draught from the same spring, Meeko had emptied it to the last drop, and had his nose down in the bottom of my cup catching the sap as it welled up with an abundance that must have surprised him. When I went away quietly he followed me through the wood to the pool at the edge of the meadow, to see what I would do next. Wherever you go in the wilderness you find Meeko ahead of you, and all the best camping grounds preempted by him. Even on the islands he seems to own the prettiest spots, and disputes mightily your right to stay there; though he is generally glad enough of your company to share his loneliness, and shows it plainly. Once I found him living all by himself on an island in the middle of a wilderness lake, with no company whatever except a family of mink, who are his enemies. He had probably crossed on the ice in the late spring, and while he was busy here and there with his explorations the ice broke up, cutting off his retreat to the mainland, which was too far away for his swimming. So he was a prisoner for the long summer, and welcomed me gladly to share his exile. He was the only red squirrel I ever met that never scolded me roundly at least once a day. His loneliness had made him quite tame. Most of the time he lived within sight of my tent door. Not even Simmo’s axe, though it made him jump twice from the top of a spruce, could keep him long away. He had twenty ways of getting up an excitement, and whenever he barked out in the woods I knew that it was simply to call me to see his discovery — a new nest, a loon that swam up close, a thieving muskrat, a hawk that rested on a dead stub, the mink family eating my fish heads, — and when I stole out to see what it was, he would run ahead, barking and chuckling at having some one to share his interests with him. In such places squirrels use the ice for occasional journeys to the mainland. Sometimes also, when the waters are calm, they swim over. Hunters have told me that when the breeze is fair they make use of a floating bit of wood, sitting up straight with tail curled over their backs, making a sail of their bodies—just as an Indian, with no knowledge of sailing whatever, puts a spruce bush in a bow of his canoe and lets the wind do his work for him. That would be the sight of a lifetime, to see Meeko sailing his boat; but I have no doubt whatever that it is true. The only red squirrel that I ever saw in the water fell in by accident. He swam rapidly to a floating board, shook himself, sat up with his tail raised along his back, and began to dry himself. After a little he saw that the slight breeze was setting him farther from shore. He began to chatter excitedly, and changed his position two or three times, evidently trying to catch the wind right. Finding that it was of no use, he plunged in again and swam easily to land. That he lives and thrives in the wilderness, spite of enemies and hunger and winter cold, is a tribute to his wits. He never hibernates, except in severe storms, when for a few days he lies close in his den. Hawks and owls and weasels and martens hunt him continually; yet he more than holds his own in the big woods, which would lose some of their charm if their vast silences were not sometimes broken by his petty scoldings. As with most wild creatures, the squirrels that live in touch with civilization are much keener witted than their wilderness brethren. The most interesting one I ever knew lived in the trees just outside my dormitory window, in a New England college town. He was the patriarch of a large family, and the greatest thief and rascal among them. I speak of the family, but, so far as I could see, there was very little family life. Each one shifted for himself the moment he was big enough, and stole from all the others indiscriminately.  It was while watching these squirrels that I discovered first that they have regular paths among the trees, as well defined as our own highways. Not only has each squirrel his own private paths and ways, but all the squirrels follow certain courses along the branches in going from one tree to another. Even the strange squirrels, which ventured at times into the grove, followed these highways as if they had been used to them all their lives. On a recent visit to the old dormitory I watched the squirrels for a while, and found that they used exactly the same paths, — up the trunk of a big oak to a certain boss, along a branch to a certain crook, a jump to a linden twig and so on, making use of one of the highways that I had watched them following ten years before. Yet this course was not the shortest between two points, and there were a hundred other branches that they might have used. I had the good fortune, one morning, to see Meeko the patriarch make a new path for himself that none of the others ever followed He had a home den over a hallway, and a hiding place for acorns in a hollow linden. Between the two was a driveway; but though the branches arched over it from either side, the jump was too great for him to take. He would rush out as if determined to try it, time after time, but always his courage failed him; he had to go down the oak trunk and cross the driveway on the ground, where numberless straying dogs were always ready to chase him. One morning I saw him run twice in succession at the jump, only to turn back. But the air was keen and bracing, and he felt its inspiration. He drew farther back, then came rushing along the oak branch, and before he had time to be afraid, hurled himself across the chasm. He landed fairly on a maple twig, with several inches to spare, and hung there with claws and teeth, swaying up and down gloriously. Then, chattering his delight at himself, he ran down the maple, back across the driveway, and tried the jump three times in succession to be sure he could do it.  After that he sprang across frequently. But I noticed that whenever the branches were wet with rain or sleet he never attempted it; and be never tried the return jump, which was uphill, and which he seemed to know by instinct was too much to attempt. When I began feeding him, in the cold winter days, he showed me many curious bits of his life. First I put some nuts near the top of an old well, among the stones of which he used to hide things in the autumn. Long after he had eaten his store, he would come and search the crannies among the stones to see if perchance he had overlooked any trifles. When he found a handful of shagbarks, one morning, his astonishment knew no bounds. His first thought was that he had forgotten them all these hungry days, and he promptly ate the biggest within sight of the store, a thing I never saw a squirrel do before. His second thought — I could see it in his changed attitude, his sudden creepings and hidings — was that some other squirrel had hidden them there since his last visit. Whereupon he carried them all off and hid them in a broken linden branch. Then I tossed him peanuts, throwing them first far away, then nearer and nearer till he would come to my window-sill. And when I woke one morning he was sitting there looking in at the window, waiting for me to get up and bring his breakfast. In a week he had showed me all his hiding places. The most interesting of these was over a roofed piazza, in a building near by. He had gnawed a hole under the eaves, where it would not be noticed, and lived there in solitary grandeur, during stormy days, in a den four by eight feet, and rain proof. In one corner was a bushel of corn-cobs, some of them two or three years old, which he had stolen from a cornfield near by in the early autumn mornings. With characteristic improvidence he had fallen to eating the corn while yet there was plenty more to be gathered. In consequence he was hungry before February was half over, and living by his wits, like his brother of the wilderness. The other squirrels soon noted his journeys to my window, and presently they too came for their share. Spite of his fury in driving them away, they managed in twenty ways to circumvent him. It was most interesting, while he sat on my window-sill eating peanuts, to see the nose and eyes of another squirrel peering over the crotch of the nearest tree, watching the proceedings from his hiding place. Then I would give Meeko five or six peanuts at once. Instantly the old hiding instinct would come back; he would start away, taking as much of his store as he could carry with him. The moment he was gone, out would come a squirrel from his concealment — and carry off all the peanuts that remained. Meeko’s wrath when he returned was most comical. The Indian legend is true as gospel to squirrel nature. If he returned unexpectedly and caught one of the intruders, there was always a furious chase and a deal of scolding and squirrel jabber before peace was restored and the peanuts eaten. Once, when he had hidden a dozen or more nuts in the broken linden branch, a very small squirrel came prowling along and discovered the store. In an instant he was all alertness, peeking, listening, exploring, till quite sure that the coast was clear, when he rushed away headlong with a mouthful. He did not return that day; but the next morning early I saw him do the same thing. An hour later Meeko appeared and, finding nothing on the window-sill, went to the linden. Half his store of yesterday was gone. Curiously enough, he did not suspect at first that they were stolen. Meeko is always quite sure that nobody knows his secrets. He searched the tree over, went to his other hiding places, came back, counted his peanuts, then searched the ground beneath, thinking, no doubt, the wind must have blown them out — all this before he had tasted a peanut of those that remained. Slowly it dawned upon him that he had been robbed and there was an outburst of wrath. But instead of carrying what were left to another place, he left them where they were, still without eating, and hid himself near by to watch. I neglected a lecture in philosophy to see the proceedings, but nothing happened. Meeko’s patience soon gave out, or else he grew hungry, for he ate two or three of his scanty supply of peanuts, scolding and threatening to himself. But he left the rest carefully where they were. Two or three times that day I saw him sneaking about, keeping a sharp eye on the linden; but the little thief was watching too, and kept out of the way. Early next morning a great hub-bub rose outside my window, and I jumped up to see what was going on. Little Thief had come back, and Big Thief caught him in the act of robbery. Away they went pell-mell, jabbering like a flock of blackbirds, along a linden branch, through two maples, across a driveway, and up a big elm where Little Thief whisked out of sight into a knot hole. After him came Big Thief, chattering vengeance. But the knot hole was too small; he could not get in. Twist and turn and push and threaten as he would, he could not get in; and Little Thief sat just inside jeering maliciously. Meeko gave it up after a while and went off, nursing his wrath. Ten feet from the tree a thought struck him. He rushed away out of sight, making a great noise, then came back quietly and hid under an eave where he could watch the knot hole. Presently Little Thief came out, rubbed his eyes, and looked all about. Through my glass I could see Meeko blinking and twitching under the dark eave, trying to control his anger. Little Thief ventured to a branch a few feet away from his refuge, and Big Thief, unable to hold himself a moment longer, rushed out, firing a volley of direful threats ahead of him. In a flash Little Thief was back in his knot hole and the comedy began all over again. I never saw how it ended; but for a day or two there was an unusual amount of chasing and scolding going on outside my windows. It was this same big squirrel that first showed me a curious trick of hiding. Whenever he found a handful of nuts on my window-sill and suspected that other squirrels were watching to share the bounty, he had a way of hiding them all very rapidly. He would never carry them direct to his various garners; first, because these were too far away, and the other squirrels would steal while he was gone; second, because, with hungry eyes watching somewhere, they might follow and find out where he habitually kept things. So he used to hide them all on the ground, under the leaves in autumn, under snow in winter, and all within sight of the window-sill, where he could watch the store as he hurried to and fro. Then, at his leisure, he would dig them up and carry them off to his den, two cheekfuls at a time. Each nut was hidden by itself; never so much as two in one spot. When he hid one under the snow he would make tracks crisscross in every direction, so that no one would notice the spot where he had been digging. For a long time it puzzled me to know how he remembered so many places. I noticed first that he would always start from a certain point, a tree or a stone, with his burden. When it was hidden he would come back by the shortest route to the window-sill; but with his new mouthful he would always go first to the tree or stone he had selected, and from there search out a new hiding place. It was many days before I noticed that, starting from one fixed point, he generally worked toward a tree or a rock in the distance. Then his secret was out; he hid things in a line. Next day he would come back, start from his fixed point and move slowly towards the distant one till his nose told him he was over a peanut, which he dug up and ate or carried away to his den. But he always seemed to distrust himself; for on hungry days he would go over two or three of his old lines in the hope of finding a mouthful that he had overlooked. This method was used only when he had a large supply to dispose of hurriedly, and not always then. Meeko is a careless fellow and soon forgets. When I gave him only a few to dispose of, he hid them helter-skelter among the leaves, forgetting some of them afterwards and enjoying the rare delight of stumbling upon them when he was hungriest — much like a child whom I saw once giving himself a sensation. He would throw his penny on the ground, go round the house, and saunter back with his hands in his pockets till he saw the penny, which he pounced upon with almost the joy of treasure-trove in the highway. Meeko made a sad end — a fate which he deserved well enough but which I had to pity, spite of myself. When the spring came on, he went back to evil ways. Sap was sweet and buds were luscious with the firs swelling of tender leaves; spring rains had washed out plenty of acorns in the crannies under the big oak, and there were fresh-roasted peanuts still at the corner windowsill, within easy jump of a linden twig; but he took to watching the robins to see where they nested, and when the young were hatched he came no more to my window. Twice I saw him with fledgelings in his mouth; and I drove him day after day from a late clutch of robin’s eggs that I could watch from my study.  He had warnings enough. Once some students, who had been friendly all winter, stoned him out of a tree where he was nest-robbing; once the sparrows caught him in their nest under the high eaves, and knocked him off promptly. A twig upon which he caught in falling saved his life undoubtedly; for the sparrows were after him and he barely escaped into a knot hole, leaving the angry horde clamoring outside. But nothing could reform him. One morning, at daylight, a great crying of robins brought me to the window. Meeko was running along a limb, the first of the fledgelings in his mouth. After him were five or six robins, whom the parents’ danger cry had brought to the rescue. They were all excited and tremendously in earnest. They cried thief! thief! and swooped at him like hawks. Their cries speedily brought a score of other birds, some to watch, others to join in the punishment. Meeko dropped the young bird and ran for his den; but a robin dashed recklessly in his face and knocked him fair from the tree. That and the fall of the fledgeling excited the birds more than ever. This thieving bird-eater was not invulnerable. A dozen rushed at him on the ground and left the marks of their beaks on his coat before he could reach the nearest tree. Again he rushed for his den, but wherever he turned now angry wings fluttered over him and beaks jabbed in his face. Raging but frightened, he sat up to snarl wickedly. Like a flash a robin hurled himself down, caught the squirrel just under his ear and knocked him again to the ground. Things began to look dark for Meeko. The birds grew bolder and angrier every minute. When he started to climb a tree he was hurled off twice ere he reached a crotch and drew himself down into it. He was safe there with his back against a big limb; they could not get at him from behind. But the angry clamor in front frightened him, and again he started for his place of refuge. His footing was unsteady now and his head dizzy from the blows he had received. Before he had gone half a limb’s length he was again on the ground, with a dozen birds pecking at him as they swooped over. With his last strength he snapped viciously at his foes and rushed to the linden. My window was open, and he came creeping, hurrying towards it on the branch over which he had often capered so lightly in the winter days. Over him clamored the birds, forgetting all fear of me in their hatred of the nest-robber. A dozen times he was struck on the way, but at every blow he clung to the branch with claws and teeth, then staggered on doggedly, making no defense. His whole thought now was to reach the window-sill.  At the place where he always jumped he stopped and began to sway, trying to summon strength for the effort. He knew it was too much, but it was his last hope. At the instant of his spring a robin swooped in his face; another caught him a side blow in mid-air, and he fell heavily to the stones below. — Sic semper Tyrannis! yelled the robins, scattering wildly as I ran down the steps to save him, if it were not too late. He died in my hands a moment later, with curious maliciousness nipping my finger sharply at the last gasp. He was the only squirrel of the lot who knew how to hide in a line; and never a one since his day has taken the jump from oak to maple over the driveway.  |