CHAPTER V

PATAGONIA

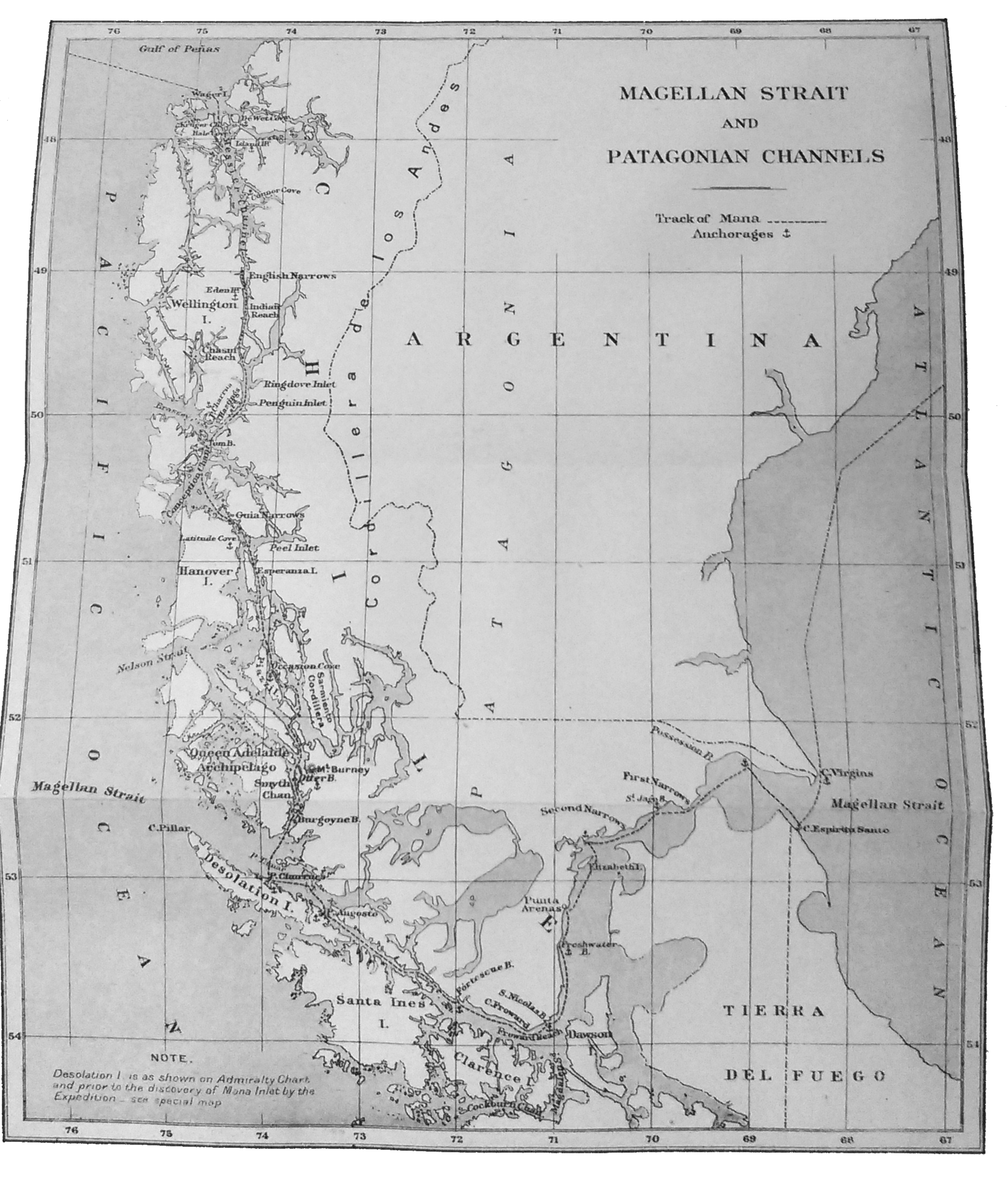

Port

Desire — Eastern Magellan Straits — Punta Arenas — Western Magellan

Straits —

Patagonian Channels

The most southerly portion

of the South

American continent, called Patagonia, first became known in the

endeavour to

find a new way into the Pacific. Magellan was commissioned by Charles

of Spain

to try to find by the south that ocean passage to the Indies which

Columbus had

sought in vain further north. He sailed in August 1519, and began his

search

along the coast at the River Plate; on October 21st, the day of the

Eleven

Thousand Virgins, he came in sight of a large channel opening out to

the west: the

promontory to the north of this channel still bears the name he

bestowed of

Cape Virgins. He proceeded cautiously, sending boats ahead to explore,

and on

November 28th entered the Pacific. When he saw the open sea he is said

to have

wept for joy, and christened the last cape "Deseado," or the "Desired."

The sea power of England,

which had been

negligible in the time of the first voyages to the New World, was

growing in

strength; and, though she had attempted no settlement on the southern

continent, she saw no reason to acquiesce in the edicts of the King of

Spain,

shutting her off from all trade with the New World. In 1578 Drake took

Magellan's route, with the object of intercepting galleons on the

Pacific

coast, and passed through the Straits in sixteen days. On entering the

Pacific

he was blown backward towards Cape Horn, and was the first to realise

that

there was another waterway, yet further south, from the Atlantic to the

Pacific. Up till this time the land had been supposed to extend to the

Antarctic.

A hundred years later

Charles II of England

sent an expedition under Sir John Narborough to explore this part of

the world

and trade with the Indians, which wintered on the eastern coast of

Patagonia.

Anson's squadron avoided

the Straits, taking

the way by the Horn.

The Chilean and Argentine

Boundary Commission

divided Patagonia between the two countries, giving the west and south

to Chile

and bisecting Tierra del Fuego, 1902.

We left

Buenos Aires on September 19th, achieving the descent of the river

without a

pilot, and for the next fortnight had a varying share of fair winds,

contrary

winds, and calms. Our chief interest was the man who had taken the

place of the

absconding steward, who shall be known as "Freeman"; we heard of him

through a seamen's home, and arranged that he should go with us to

Punta

Arenas, to which place he wished for a passage. He was a clean-looking

"Britisher,"

who for the last seven years had been knocking about South America, He

brought

with him a gramophone, and a Parabellum automatic pistol, with which he

proved

an excellent shot, and he made it a sine

qua non that we should find room on board for his saddle; thus was

my

knowledge increased of the necessary equipment of an indoor servant. We

paid

him at the rate of £100 a year, and though we found that he could

neither boil

a suet pudding nor lay a table, so enlightening were his accounts of

up-country

life that we did not grudge him the money.

We

flatter ourselves our experience in detecting mendacity would qualify

us as

police-court magistrates, but we never saw any reason to doubt the

substantial

accuracy of Freeman's stories. His experience dated back to the time

when mares

of two or three years old were sold for ten shillings, or were boiled

down for

fat, as, after the Spanish fashion, no man would demean himself by

riding one.

He had at one time ridden across the continent from the Patagonian to

the

Chilean coast, a journey of six weeks, half of which time he never saw

a human

being; he was followed all the way by a dog, though the poor animal was

once

two or three days without water; it got left behind at times, but

always managed

to pick up his trail. He was most candid about the means by which he

had made

money when at one time employed on the railway, for honesty was not in

his

opinion the way that the game was played in South America, and

therefore no

individual could afford to make it part of his programme: it did happen

to be

one of the rules on Mana, and we

never knew him break it. He was once running away after some drunken

escapade,

when a policeman appeared and took pot-shots at him with a rifle.

Freeman

turned and dropped him with his revolver; he did it the more

reluctantly as he

knew and liked the man. Happily the shot was not fatal, and he felt

convinced that

he himself had not been recognised.

After,

therefore, carefully arranging an alibi elsewhere he returned, condoled

with

the victim on the lawless deed, and gave him what assistance he could;

he felt,

however, that that part of the country had become not very "healthy,"

and subsequently moved on. Even our experiences of the ports had

scarcely

prepared us for the cynical indifference to human life which his

experiences

incidentally revealed as an everyday affair in "the camp." In

sparsely inhabited districts, with their very recent population, the

factors

are absent through which primitive societies generally secure justice,

clans do

not exist, families are the exception, and in almost every case a man

is simply

a unit. The more advanced methods of keeping the peace have either not

been

formed or are not effective, for crime is often connived at by the

authorities

themselves. The result is that the era of vendetta and private revenge

seems

civilised in comparison with a state of things where no notice is taken

of

murder, and the victim who falls in a brawl or by fouler means simply

disappears unknown and unmissed, while the murderer goes scot-free to

repeat

his crime on the next occasion.

Freeman

had, inter alia, been employed on one

of the farms in Patagonia, along the coast of which we were sailing,

and told

tales of the pumas, or South American lions, which abounded in a

certain

neighbourhood. This district had railway connection with a little

anchorage

known as Port Desire, and as one of our intervals in harbour was now

due S.

arranged to turn in here, and go up-country with him to try to get a

shot at

the animals. We therefore put into the port on October 3rd. It is a

small

inlet, of which the surrounding country is covered with grass, but flat

and dreary

in the extreme, the only relief being a distant vision of blue hills.

Sir John

Narborough, who spent part of the winter here in 1670, said he never

saw in the

country "a stick of wood large enough to make the handle of a

hatchet.''

The human

dwellings are a few tin shanties. In a walk on shore we were able to

see in a

gully, a few remains of the walls of the old Spanish settlement. As to

the

puma, fortunately from its point of view, the railway service left a

good deal

to be desired. We arrived on Friday, and there turned out to be no

train till

the following Tuesday, so it lived to be shot another day — unless

indeed it

met a more ignominious end, for the South American lion is so unworthy

of its

name that it is sometimes killed by being ridden down and brained with

a

stirrup-iron. We took three sheep on board, as mutton at twopence a

pound

appealed to the housekeeping mind, and were able to secure some water,

which is

brought down by rail; it was a relief to have our tanks well supplied,

as the

ports further down the coast are defended by bars, and would have been

difficult of access in bad weather. Drake, on whose course we were now

entering, selected St. Julian, the next bay to the southward, for his

port of

call before entering the Straits of Magellan; it was there he had

trouble with

his crew, and was obliged to hang Doughty.

We sailed

from Port Desire on Monday morning, but were not to say good-bye to it

so

speedily. We soon encountered a strong head-wind, with the result that

Wednesday evening found us fifteen miles backwards on a return journey

to

Buenos Aires, and the whole of Thursday saw us still within sight of

it. We

amused ourselves by discussing the voyage, which had now lasted more

than seven

months. One of the company declared that he had lost all sense of time

and felt

like a native or an animal: things just went on from day to day; there

was

neither before nor after, neither early nor late. It did not, he said,

seem

very long since we left Falmouth, but on the other hand our stay at

Pernambuco

was certainly in the remote past, and so with everything else. We had

now, in

fact, done about three-quarters of the distance from Buenos Aires

towards the

Straits of Magellan, and had 300 miles left before we reached their

entrance at

Cape Virgins.

Ever

since the Expedition was originally projected the passage of the

Straits had

been spoken of in somewhat hushed tones; but now, when with a more

favourable

wind we began to approach them, instead of going into Arctic regions,

as some

of us had anticipated, the weather improved, the sun went south faster

than we

did, and the days lengthened rapidly. Our numerous delays had at least

one

fortunate result — they secured us a much better time of year in the

Straits

than we had expected would fall to our lot. The feeling in the air was

that of

an English April, bright and sunny, but fresh; we kept the saloon cold

on

principle during the daytime, living in big coats; in the evening we

had on the

hot-water apparatus, so as to go warm to bed. It was quite possible to

write on

deck, and the sea was almost too beautifully calm. We had a great many

ocean

callers, who seemed attracted by the vessel: porpoises tumbled about

the bows

till we could nearly stroke them, a whale would go round and round the

yacht,

coming up to blow at intervals, while seals reared their heads and

shoulders

out of the waters and looked at us in a way that was positively

bewitching;

once a whale and seal paid us a visit at the same time. One night S.,

who was

keeping a watch for one of the officers who was indisposed, was

interested in

watching the gulls still feeding during the dark hours.

At 10

p.m. on October 15th the light of Cape Virgins was sighted, and we woke

to find

ourselves actually in the Straits of Magellan. The Magellan route, as

compared

with that by the Horn, is not only a short road from the Atlantic to

the

Pacific, cutting off the islands to the south of the continent, but

ensures

calm waters, instead of the stupendous seas of the Antarctic Ocean. For

a

sailing-ship, however, the difficulties are great; the prevailing wind

is from

the west, and there is no space for a large vessel to beat up against

it, nor

does she gain the advantage that can be derived from any slight shift

of wind;

outside the gale may vary a point or two, but within the channel it

always

blows straight down as in a gully. The early mariners could overcome

these

obstacles through the strength of their crews; in case of necessity

they

lowered their boats and towed the ship, but the vessels of the present

no longer

carry sufficient men to make such a proceeding possible. Sailing-ships

therefore take to-day the Cape Horn route, in spite of its well-known

delays,

trials, and hardships. When later the German cruiser turned up at

Easter Island

with her captured crews, the great regret of the latter was that they

had been

taken just too late, after they had gone through the unpleasantness of

the

passage round the Horn.

The first

sight of Tierra del Fuego is certainly disappointing. The word calls up

visions

of desolate snowy mountains inhabited by giants; what is seen are low

cliffs,

behind which are rolling downs, sunny and smiling, divided up into

prosaic

sheep farms. A reasonably careful study of the map would of course have

shown

what was to be expected, as on the Atlantic coast the plains continue

to the

extreme south of the continent, while the chain of the Andes looks only

on to

the Pacific. Nevertheless^ if not thrilling, it was at least enjoyable

to be in

a stretch of smooth water, with Patagonia on the north and Tierra del

Fuego on

the south. The land on either hand is excellent pasture for sheep, and

there is

said to be sometimes as much as 97 per cent, increase in a flock. The

largest

owners are one or two Chilean firms, but the shepherds employed are

almost all

Scotsmen, and indeed the scenery recalls some of the less beautiful

districts

in the Highlands. When sheep-farming was established, the Indians, not

unnaturally from their point of view, made raids on the new animals,

with the

result that the representatives of the company were consumed with wrath

at

seeing their stock eaten by lazy natives; they started a campaign of

extermination, shooting at sight and offering a reward for Indian

tongues. Our

friend Freeman had worked on one of the farms, which had a stock of

200,000

sheep, and the information he gave on this head was fully confirmed

later in

conversations at Punta Arenas. The destruction of the Indians was

spoken of

there as a matter for regret, but as rendered inevitable by

circumstances.

The navigation

through the straits of a craft like ours makes it necessary to anchor

in the

dark hours: the first night we spent off the Fuegian coast, in sight of

one of

the pillars which define the boundary of Chile and Patagonia; the

second we lay

in Possession Bay, which is on the Patagonian side. We had time at the

latter

anchorage to examine the pathetic wreck of a steamer, which had gone

aground.

She was a paddle-boat, which was being towed presumably from one lake

or river

area to another, and had to be cut adrift. Even in such an unheroic

vessel it

was touching to see the sign of departed and luxurious life cast away

on this

lonely shore, stained-glass doors bearing the inscription of

"smoking" or "dining-room," and good mahogany fittings such

as washing-stands still in place. It is said that the outer coast is

strewn

with wrecks containing valuable articles which it is worth no one's

while to

remove. S. walked up to the neighbouring lighthouse, and was presented

with

three rhea eggs.

FIG. 8. — IN THE

MAGELLAN STRAITS.

S. and an ostrich.

The next

morning we were under way at 5 o'clock, in order to pass with the

correct tide

through what are known as the First Narrows. The current here is so

strong that

it would have been impossible for us to make headway against it; as it

was, the

wind sank soon after we started, and we only just accomplished the

passage,

anchoring in St. Jago Bay. The following day, Sunday, we negotiated

successfully the Second Narrows. From our next anchorage we saw from

the yacht

several rhea, or South American ostriches, on a small promontory. S.

went

ashore on the point and shot two of them, while Mr. Ritchie and Mr.

Gillam, who

had landed on the neck of the promontory, endeavoured to cut off the

retreat of

the two remaining birds. The one marked by Mr. Ritchie went through

some water

and escaped him; the onlookers then viewed with much interest a duel

between

Mr. Gillam on the one hand, running about in sea-boots armed with a

revolver,

and the last ostrich on the other, vigorously using its legs and wings

and on

its own ground. Victory remained with the bird, which reached the

mainland

triumphantly, or at least disappeared behind a bush and was no more

seen. Seven

miles south-west of the Second Narrows lies Elizabeth Island, so named

by

Drake. We took the passage known as Queen's Road on the Fuegian side of

the

island, and reached Punta Arenas next afternoon, Monday, October 20th.

We had

intended to be there for two or three days only, but fate willed

otherwise, and

we sat for weeks in a tearing wind among small crests of foam, gazing

at a

little checkered pattern of houses on the open hillside opposite.

It will

be remembered that the motor engine, to our great chagrin, was

practically

useless through heated bearings, and that all our endeavours at Buenos

Aires to

diagnose and remedy its ailment had been ineffectual. We had

consequently to

rely on passing through the Straits either under sail, or, as the late

Lord

Crawford had suggested to us before starting, through getting a tow

from some

passing tramp by means of a £50 cheque to the skipper, a transaction

which

would probably not appear in their log. However, in mentioning our

disappointment to the British Consul, who was one of an engineering

firm, he

and his partner hazarded the suggestion that the defect lay, not in the

engine,

where it had been sought, but in the installation; that the shaft was

probably

not "true." They bravely undertook the job of overhauling it on the

principle of "no cure, no pay," and were entirely justified by the

result. The alteration was to have been finished in ten days, but there

were

the usual delays, one of which was a strike at the "shops," when a

piece of work could only be continued by inducing one man to ply his

trade

behind closed doors while S. turned the lathe. It was six weeks before

the

anxious moment finally came for the eight hours' trial, which had been

part of

the bargain, but the motor did it triumphantly without turning a hair.

We found

what consolation for the delay was possible in the reflection that we

had at

least done all in our power to guard against such misfortune. The

engine had

been purchased from a first-class firm who had done the installation;

the work

had been supervised on our behalf by a private firm and passed by

Lloyds; nevertheless

it was peculiarly aggravating, for not only did it involve great money

loss,

but it sacrificed some of the strictly limited time of our navigator

and

geologist. We had the pleasure at this time of welcoming the said

geologist,

Mr. Lowry-Corry, who now joined the Expedition after successfully

completing

his work in India.

Punta

Arenas, with which we became so well acquainted, is a new and

unpretentious

little town, but it is the centre of the sheep-grazing districts, and

its shops

are remarkably good. Anything in reason can be purchased there, and on

the

whole at more moderate prices than elsewhere in South America. The

beautiful

part of the Straits is not yet reached, and save for some distant views

the

place is ugly, but it gives a sensation of cleanliness and fresh air,

and our

detention might have been worse. There is indeed, on occasion, too much

air,

for it was at times impossible to get from the ship to the shore or

vice versa,

and if members of the party were on land when the wind sprang up they

had to

spend the night at the little hotel; the waves were not big, but the

gales were

too strong for the men to pull against them. I was with reluctance

obliged to

give up some promising Spanish lessons, with which I had hoped to

occupy the

time, for it was impossible to be sure of keeping any appointment from

the

yacht. Punta Arenas boasts an English chaplain, and Boy Scouts are in

evidence.

The chief celebrity is an Arctic spider-crab, which multiplies in the

channels

and is delicious eating, but we never discovered anything of much local

interest.

I made

one day a vain attempt to find the graves of the officers and crew of

H.M.S. Dotterel, which was blown up off Sandy

Point some thirty years ago. The cemetery overlooked the Straits; it

was desolate

and dreary, the ground being unlevelled and the tufted grass, with

which it was

covered, unkept and unmown. Most of the graves were humble enclosures,

some of

which gave the impression of greenhouses, being covered with erections

of wood

and glass; but here and there were small mausoleums, the property of

rich

families or corporations. It is the custom with some Chileans so to

preserve

the remains that the faces continue visible; an Englishman at Santiago

told us

that after a funeral which he had attended, the mourners expressed a

desire to

"see Aunt Maria," whereupon the coffin of a formerly deceased

relative was taken down from its niche for her features to be

inspected. The

police of Punta Arenas had their home together in a large vault, which

was apparently

being prepared for a new occupant; while the veterans of '79 (the war

between

Chile and Peru) slept as they had fought, side by side. There was

apparently no

Protestant corner, for the graves of English, Germans, and Norwegians

were

intermingled with those of Chileans. The resting-places of all, rich

and poor

alike, were lovingly decorated with the metal wreaths so prevalent in

Latin

countries, but unattractive to the English eye. Whilst I wandered among

the

tombs a storm burst, which had been gathering for some time amongst

distant

mountains, and chilly flakes of snow swept down in force, with biting

wind and

hail. I sheltered in the lee of a mausoleum, on whose roof balanced a

large

figure of the angel of peace bearing the palm-branch of victory, and

the

inscription on which showed it to be the property of a wealthy family,

whose

name report specially connected with the poisoning of Indians. The

landscape

was temporarily obscured by the driving storm, not a soul was in sight,

and the

iron wreaths on hundreds of graves rattled with a weird and ghostly

sound.

Presently, however, the tempest passed and the sun shone out, while

over the

Straits, towards the Fuegian land, there came out in the sky a

wonderful arc of

light edged by the colours of the rainbow, which turned the sea at its

foot

into a translucent and sparkling green.

But if

there was not much occupation on shore, the unexpected length of our

stay

provided us unpleasantly with domestic employment. We had on arrival

parted

from our friend Freeman, his object in coming to Punta Arenas was, it

transpired, to collect the remainder of a sum due to him in connection

with the

sale of a skating-rink, which he had at one time started there and run

with

considerable success: we were proud to think that service on an English

scientific vessel would now be added to his experiences. Life below

deck was

then in the hands of Luke, the under-steward, who, as will be

remembered by

careful readers, had been the salvation of the inner man during our

first gale

in the North Atlantic . We had engaged him at Southampton on the

strength of a

character from a liner on which he had served in some subordinate

capacity, and

he. signed on for the voyage of three years at the rate of £2 10s. a

month.

Though never what registry offices would call "clean in person and

work," he plodded through somehow, and again in the Freeman episode

rescued the ship from starvation; we accordingly doubled his wages as a

testimonial of esteem. My feelings can therefore be imagined when one

morning,

after we had been some weeks at Punta Arenas, I was told that Luke was

not on

board and his cabin was cleared. He had somehow in the early morning

eluded the

anchor watch and had gone off in a strange boat. A deserter forfeits of

course

his accumulated wages, which, by a probably wise regulation, are

payable to

Government and not to the owner; but there is nothing to prevent a man

who is

leaving a vessel recouping himself by means of any little articles that

he may

judge will come in handy in his new career. The one that I grudged most

to Luke

was my cookery book, to which he had become much attached, and which

was never

seen again after his departure; it was really a mean theft, from which

I

suffered much in the future.

S.

offered, through the police, a reward for his detention, and enlarged

his

knowledge of the town by going personally through every low haunt, but

without

success. A rumour subsequently reached us that a muffled figure had

been seen

going on board one of the little steamers which plied backwards and

forwards to

the ports in Tierra del Fuego, and we heard, when it was too late, that

Luke

had been enticed to a sheep farm there, with the promise of permanent

employment at £10 a month, with £2 bonus during shearing-time, which

was then

in progress. The temptation was enormous, and I have to this day a

sneaking

kindliness for Luke, but for those who tempted him no pardon at all.

The

condition in which the successive defaulters had left their quarters is

better

pictured than described, and so stringent is the line of ship's

etiquette

between work on deck and below, that, as the simplest way and for the

honour of

the yacht, the Stewardess did the job of cleaning out cabin and pantry

herself.

The moral for shipowners is — do not dally in South American ports.

Now began

a strange hunt in the middle of nowhere for anything that could call

itself a

cook or steward. The beachcombers who applied were marvellous; one

persistent

applicant was the pianist at the local cinema; our expedition, as

already discovered,

had a certain romantic sound, which was apt to attract those who had by

no

means always counted the cost. Mail steamers pass Punta Arenas every

fortnight,

once a month in each direction, and these we now boarded with the tale

of our

woes. Both captain and purser were most kind in allowing us to ask for

a

volunteer among the stewards, but the attempt was only temporarily

successful;

the routine work of a big vessel under constant supervision proved not

the

right training for such a post as ours.

FIG. 9. — PUNTA

ARENAS.

Finally,

we were told of a British cook who had been left in hospital by a

merchant ship

passing through the Straits. The cause of his detention was a broken

arm,

obtained in fighting on board; this hardly seemed promising, but the

captain

was reported to have said that he was "sorry to lose him," and we

were only too thankful to get hold of anything with some sort of

recommendation. On the whole Bailey was a success. He too had knocked

about the

world; at one time he had made money over a coffee-and-cake stall in

Australia,

and then thrown it away. We had our differences of course; he once, for

instance, told me that as cook he took "a superior position on the

ship's

books to the stewardess," but his moments of temper soon blew over. I

shall always cherish pleasant memories of the way in which he and I

stood by

one another for weeks and months in a position of loneliness and

difficulty;

but this is anticipating.

As

departure drew near, provisioning for the next stage became a serious

business,

as, with the exception of a few depots for shipwrecked mariners, there

was no

possibility of obtaining anything after we sailed, before we reached

our

Chilean destination of Talcahuano. S.'s work was more simple, as he had

only to

fill up to the greatest extent with coal and oil, knowing that at the

worst the

channels provide plenty of wood and water.

The next

few weeks, when we traversed the remainder of the Magellan Straits and

the

Patagonian Channels, were the most fascinating part of the voyage. The

whole of

this portion of South America is a bewildering labyrinth of waterways

and

islands; fresh passages open up from every point of view, till the

voyager

longs to see what is round the corner, not in one direction, but in

all. It

has, too, much of the charm of the unknown: such charts as exist have

been made

principally by four English men-of-war at different periods, the

earliest being

that of the Beagle, in the celebrated

voyage in which Darwin took part. A large portion of the ways and

inlets are,

however, entirely unexplored. The effect of both straits and channels

is best

imagined by picturing a Switzerland into whose valleys and gorges the

sea has

been let in; above tower snow-clad peaks, while below precipices,

clothed with

beautiful verdure, go straight down to the water's edge. The simile of

a

sea-invaded Alps is indeed fairly accurate, for this is the tail of the

Andes

which has been partially submerged. The mountains do not rise above

5,000 feet,

but the full benefit of the height is obtained as they are seen from

the

sea-level. The permanent snow line is at about 1,200 feet. The depths

are very

great, being in some places as much as 4,000 feet, and the only places

where it

is possible to anchor are in certain little harbours where there is a

break in

the wall of rock. These anchorages lie anything from five miles to

twenty or

thirty miles apart, and as it was impossible to travel at night it was

essential to reach one of them before dark. If for any reason it did

not prove

feasible to accomplish the necessary distance, there was no option but

to turn

back in time to reach the last resting-place before daylight failed,

and start

again on the next suitable day. On the other hand, when things were

propitious,

we were able on occasion to reach an even further harbour than the one

which

had been planned.

The

proceeding amusingly resembled a game, played in the days of one's

youth, with

dice on a numbered board, and entitled "Willie's Walk to Grandmamma":

the player might not start till he had thrown the right number, and

even when

he had begun his journey he might, by an unlucky cast, find that he was

"stopping to play marbles" and lose a turn, or be obliged to go back

to the beginning; if, however, he were fortunate he might pass, like an

express

train, through several intermediate stopping-places, and outdistance

all

competitors. The two other sailing yachts with whose record we competed

were

the Sunbeam in 1876 and the Nyanza in

1888: the match was scarcely a

fair one, as the Sunheam had strong

steam power and soon left us out of sight, while the Nyanza,

though a much bigger vessel, had no motor, and we halved

her record.

It will

be seen that it was of first-rate importance to make the most of the

hours of

daylight, which were now at their longest, and to effect as early a

start as

possible, so that in case of accident or delay we should have plenty of

time in

hand before dark. We therefore, long before such became fashionable,

passed a

summer-time bill of a most extended character, the clock being put five

hours

forward. Breakfast was really at 3 a.m., and we were under way an hour

later,

when it was broad daylight; but as the hours were called eight and nine

everyone felt quite comfortable and as usual, it was a great success.

The difficulty

lay in retiring proportionately early. Stevenson's words continually

rose to

mind: "In summer quite the other way — I have to go to bed by day."

The greatest drawback was the loss of sunset effects; we should,

theoretically,

have had the sunrise instead, but the mornings were often grey and

misty, and

it did not clear till later in the day.

One of

the charms of the channels, is the smoothness of the water: we were

able to

carry our cutter in the davits as well as the dinghy. It also suited

the motor,

which proved of the greatest use, entirely redeeming its character,

there is no

doubt however, that to become accustomed to sailing is to be spoilt for

any

other method of progression. The photographers accomplished something,

but the

scenery scarcely lends itself to the camera and the light was seldom

good. The

water-colour scribbles with which I occupied myself serve their purpose

as a

personal diary.

We

speculated from time to time whether these parts will ultimately turn

into the

"playground of South America," when that continent becomes densely

populated after the manner of Europe, and amused ourselves by selecting

sites

for fashionable hotels: golf-courses no mortal power will ever make. On

the

whole the probability seems the other way, for the climate is against

it; it is

too near to the Antarctic to be warm even under the most favourable

conditions,

and the Andes will always intercept the rain-clouds of the Pacific. One

of the survey-ships

chronicled an average of eleven hours of rain in the twenty-four, all

through

the summer months. We ourselves were fortunate both in the time of year

and in

the weather. It resembled in our experience a cold and wet October at

home; but

there were few days, I cannot recall more than two, when we lost the

greater part

of the view through fog and rain. On the rare occasions when it was

sunny and

clear the effect was disappointing, and less impressive than when the

mountains

were seen partially veiled in mist and with driving cloud. The last

hundred

miles before the Gulf of Peñas it became markedly warmer, and the

steam-heating

was no longer necessary.

It was

far from our thoughts that exactly one year later these same channels

would

witness a game of deadly hide-and-seek in a great naval war between

Germany and

England. In them the German ship Dresden lay

hidden, after making her escape from the battle of the Falkland

Islands, while

for two and a half months English ships looked for her in vain. They

explored

in the search more than 7,000 miles of waterway, not only taking the

risks of

these uncharted passages, but expecting round every corner to come upon

the

enemy with all her guns trained on the spot where they must appear.

We left

Punta Arenas on Saturday, November 29th, 1913, spending the night in

Freshwater

Bay, and the next afternoon anchored in St. Nicholas Bay, which is on

the

mainland. Opposite to it, on the other side of the Straits, is Dawson

Island,

and separating Dawson from the next island to the westward is Magdalen

Sound,

which leads into Cockburn Channel; it was in this last that the Dresden found her first hiding-place

after escaping from Sturdee's squadron and obtaining an illicit supply

of coal

at Punta Arenas. St. Nicholas Bay forms the mouth of a considerable

river, the

banks of which are clothed with forests which come down to the sea;

near the

estuary is a little island, and on it there is a conspicuous tree. Mr.

Corry

and I went out in the boat, and found affixed to the tree a number of

boards

with the names of vessels which had visited the place. Jeffery

scrambled up and

added Mana's card to those already

there. This was our first introduction to a plan frequently encountered

later

in out-of-the-way holes and corners, and which subsequently played a

part in

the war. At the outbreak of hostilities the

Dresden was in the Atlantic, and had to creep round the Horn to

join the

squadron of Von Spee in the Pacific. She put into Orange Bay, one of

the

furthest anchorages to the south; there she found that many months

before the Bremen had left her name on a similar

board. Moved by habit someone on the cruiser wrote below it "Dresden,

September 11th, 1914";

then caution supervened, and the record was partially, but only

partially,

obliterated; there it was shortly afterwards read by the British ships Glasgow and Monmouth, and formed a

record of the proceedings of the enemy.

FIG. 10 — RIVER

SCENE, ST. NICHOLAS BAY

On

Monday, December ist, we started at daylight and made our way with

motor and

sail as far as Cape Froward, the most southerly point of the Straits;

but the

sea was running too high to proceed. We had to retrace our steps, and

cast

anchor again in St. Nicholas Bay. This time S. and I were determined to

explore

the river, so, after an early luncheon, in order to get the benefit of

the

tide, we made our way up it in the cutter. It was most pleasant rowing

between

the banks of the quiet stream, and so warm and sheltered that we might

almost

have imagined ourselves on the Cherwell, if the illusion had not been

dispelled

by the strange vegetation which overhung the banks,, amongst which were

beautiful flowering azaleas. Every here and there also a bend in the

course of

the river gave magnificent views of snow-clad peaks above. A happy

little

family of teal, father, mother, and children, disported themselves in

the

water. Later in the voyage, as the mountains grew steeper, we had many

waterfalls, but never again a river which was navigable to any

distance. Some

of the crew had been left to cut firewood, and we found on our return

that they

had achieved a splendid collection, which Mr. Ritchie and Mr. Corry had

kindly

been helping to chop. Burning wood was not popular in the galley, but

we were

anxious to save our supplies of coal.

Tuesday,

December 2nd, we again left the bay, and this time were more fortunate.

It was

misty and sunless, but as we rounded Cape Froward it stood out grandly,

with

its foot in grey seas and with driving clouds above. We had now

definitely

entered on the western half of the Straits and were amongst the spurs

of the

Andes. As the day advanced the wind freshened^ the clouds were swept

away, and

blue sky appeared, while the sea suddenly became dark blue and covered

with a

mass of foaming, tumbling waves; on each coast the white-capped

mountains came

out clear and strong. This part of the channel, which is known as

Froward

Reach, is a path of water, about five miles wide, lying between rocky

walls;

and up this track Mana beat to

windward, rushing along as if she thoroughly enjoyed it. Every few

minutes came

the call "Ready about, lee oh!” and over she went on a fresh tack,

travelling perfectly steadily, but listed over until the water bubbled

beneath

the bulwarks on the lee side. It would have been a poor heart indeed

that did

not rejoice, and every soul on board responded to the excitement and

thrill of

the motion: that experience alone was worth many hundred miles of

travel. As

evening came the wind sank, and we were glad of the prosaic motor to

see us

into our haven at Fortescue Bay.

The next

day the wind was too strong to attempt to leave the harbour, and we

went to bed

with the gale still raging, but during the night it disappeared, and

before

dawn we were under way. As light and colour gradually stole into the

dim

landscape, the grey trunks and brown foliage of trees on the near

mountainsides

gave the effect of the most lovely misty brown velvet. Rain and mist

subsequently obscured the view, but it cleared happily as we turned

into the

harbour of Angosto on the southern side of the channel. Rounding the

corner of

a narrow entrance, we found ourselves in a perfect little basin about a

quarter

of a mile across, surrounded with steep cliffs some 300 feet in height,

on one

side of which a waterfall tore down from the snows above. Our geologist

reported it as a glacier tarn, which, as the land gradually sank, had

been

invaded by the sea. We left it with regret at daylight next morning.

FIG. 11 — CAPE

FROWARD, MAGELLAN STRAITS.

Looking East.

The

Straits became now broader and the scenery was more bleak, the great

grey

masses being scarcely touched with vegetation till they reached the

water's

edge. It was decided to spend the night at Port Churruca in Desolation

Island,

rather than at Port Tamar on the mainland opposite, which is generally

frequented by vessels on entering and leaving the Straits. We passed

through

the entrance into a rocky basin, but when we were at the narrowest part

between

precipitous cliffs the motor stopped. It had been frequently pointed

out, when

we were wrestling with the engine, how perilous would be our position

if

anything went wrong with it in narrow waters. I confess that I held my

breath.

S. disappeared into the engine-room, the Navigator's eyes were glued to

the

compass, and the Sailing-master gave orders to stand by the boats in

case it

was necessary to run out a kedge anchor and attach the yacht to the

shore. It

was a distinct relief when the throb of the motor was once more heard;

the

difficulty had arisen from the lowness of the temperature, which had

interfered

with the flow of the oil. The ship, how ever, was luckily well under

control,

with the wind at the moment behind her. In an inner basin soundings

were taken,

“twenty-five fathoms no bottom, thirty fathoms no bottom," till, when

the

bowsprit seemed almost touching the sheer wall of rock, the Nassau

Anchorage

was found and down went the hook.

We grew

well acquainted with Churruca, as we were detained there for five days;

Saturday through the overhauling of the engine; Sunday, Monday, and

Tuesday by

bad weather; of Wednesday more anon. The position was not without a

certain

eeriness: we lay in this remote niche in the mountains, while the storm

raged

in the channel without and in the peaks above; at night, after turning

in, the

gale could be heard tearing down from above in each direction in turn,

and the

vessel's chain rattling over the stony bottom as she swung round to

meet it.

The heavy rain turned every cliff-face into a multitude of waterfalls,

which

vanished at times into the air as a gust of wind caught t he j et of

water and

converted it into a cloud of spray. Although the weather prevented our

venturing outside, it was quite possible to explore the port by means

of the

ship's boats. It proved not unlike Angosto, but on a larger and more

complicated scale. Beyond our inner anchorage, although invisible from

it, was

a further extension known as the Lobo Arm, and there were also other

small

creeks and inlets

Even the

prosaic Sailing Directions venture on the statement that the scenery at

Port

Churruca is "scarcely surpassed," and one of the fiords must be

described, although the attempt seems almost profane. In its narrow

portion it

was about a mile in length and from loo to 200 yards in width; the

sheer cliffs

on either hand were clothed to the height of many hundreds of feet with

various

forms of fern and most brilliant moss. Above this belt of colour was

bleak

crag, and higher again the snow-line. The gorge ended in a precipice,

above

which was a mountain-peak; a glacier descending from above had been

arrested in

its descent by the precipice and now stood above it, forming part of

it, a

sheer wall of ice and snow as if cut off by a giant knife. There was

little

life to be seen, but an occasional gleam was caught from the white

breast of a

sea-bird against the dark setting of the ravine . In one part , high up

on the

cliff, where the wind was deflected by a piece of overhanging rock, was

a

little colony of nests; the mother birds and young broods sat on the

edge in

perfect shelter, even when to venture off it was to be beaten down on

to the

surface of the water by the strength of the wind. Some of our party

visited the

fiord on a second occasion to try to obtain photographs; it was blowing

at the

time a severe gale, and the effect was magical. The squalls, known as

"williwaws," rushed down the ravine in such force that the powerful

little launch was brought to a standstill. They lashed the water into

waves,

and then turned the foaming crests into spray, till the whole surface

presented

the aspect of a fiercely boiling cauldron, through which glimpses could

be

caught from time to time of the dark cliffs above.

FIG. 12. — THE

GLACIER GORGE,

PORT CHURRUCA.

While S.

and I were visiting the glacier gorge, the two other members of the

party were

exploring the last portion of the inlet named on the chart the Lobo

Arm. It

terminated on low ground, on which stood the frame of an Indian hut,

and pieces

of timber had been laid down to form a portage for canoes. A few steps

showed

that the low ground extended only for some i6o yards, while beyond this

was another

piece of water which had the appearance of an inland lake, some three

miles

long and a mile wide. The portage end of the water was vaguely shown on

the

chart of Port Churruca, but there was no indication of anything of the

kind on

the general map of Desolation Island. Our curiosity was mildly excited,

and we

all visited the place; one of our number remarked that "the water was

slightly salt," another that there "were tidal indications," a

third that "from higher ground the valley seemed to go on

indefinitely."

At last the map was again and more seriously examined, and it was seen

that,

while there were no signs of this water, there were on the opposite

side of the

island the commencements of two inlets from the open sea, neither of

which had

been followed up: the more northerly of these was immediately opposite

Port

Churruca. “If," we all agreed, “our lake is not a lake at all, but a

fiord" — and to this every appearance pointed — "it is in all

probability the termination of this northern inlet, and Desolation

Island is

cut in two except for the small isthmus with the portage." Then a great

ardour of exploration seized us, Mr. Corry fell a victim to it, Mr.

Gillam fell

likewise, and we refused to be depressed by Mr. Ritchie's dictum that

it had

"nothing to do with serious navigation." We wrestled with a

conscientious conviction that it had certainly nothing to do with

Easter

Island, and we ought to go forward at the earliest possible moment, but

the

exploration fever conquered. We discussed the possibility of getting

the motor-launch

over the portage, and were obliged reluctantly to abandon it as too

heavy, but

it was concluded that it would be quite feasible with the cutter.

The next

day proved too wet to attempt anything, but Wednesday dawned reasonably

fine,

though with squalls at intervals. Great were the preparations, from

compasses,

notebooks, and log-lines, to tinned beef and dry boots. At last at

11.30 (or

6.30 a.m. by true time) we sallied forth. The launch towed us down the

Lobo

Arm, and then came the work of passing the boat across the isthmus, at

which

all hands assisted. It was the prettiest sight imaginable; the portage,

which

had been cut through the thick forest undergrowth, had the appearance

of a long

and brilliant tunnel between the two waters, it was carpeted with

bright moss

and overhung by trees which were covered with lichen (fig. 14). The

bottom was

soft and boggy, and I at one time became so firmly embedded that I

could not

get out without assistance. In less than half an hour the boat was

launched on

the other side, and Mr. Corry, Mr. Gillam, our two selves, and two

seamen set

forth on our voyage. Soon after starting the creek divided, part going

to the

north-west and part to the south-east. We decided to follow the latter

as apparently

the main channel.

We rowed

for an hour and a quarter, taking our rate of speed by the log. The

mountains

on each side were of granite, showing very distinct traces of ice

action. At 2

p.m. we landed on the left bank for luncheon. It was, it must be

admitted, a

somewhat wet performance; the soaked wood proved too much even for our

expert

campers-out, who had been confident that they could make a fire under

all

circumstances, and had disdainfully declined a proffered thermos.

Enthusiasm

was, however, undamped. Mr. Corry ascended to high ground and

discovered that

there was another similar creek on the other side of the strip of

ground on

which we had landed, which converged towards that along which we were

travelling. After rowing for an hour and a half we reached the point

where the

two creeks joined; here we landed and scrambled up through some

brushwood to

the top of a low eminence. Looking backwards we could see up both

pieces of

water, while looking forward the two fiords, now one, passed at right

angles,

after some four miles, into a larger piece of water. This was where we

had

expected to find the open sea, and some distant blue mountains on the

far

horizon were somewhat of an enigma. As we had to row back against a

head wind,

it was useless to think of going further, unless we were prepared to

camp out,

so all we could do was to make as exact sketches as possible to work

out at

home.

The

return journey was easier than had been expected, for the wind dropped;

we kept

this time to the right bank, and stopped for "tea" by some rocks,

which added mussels to the repast for the taking. The portage was

gained four

hours after the time that the rest of the crew had been told to meet us

there;

and it was a relief to find that they had possessed their souls with

patience. Mana was finally reached at 11 p.m. It

was found by calculating the speed at which we had travelled and its

direction,

that our creek had led into the more southerly of the unsurveyed

inlets, and

not as we had expected into that to the northward. The distant blue

hills were

islands. Like all great explorers, from Christopher Columbus downwards,

our

results were therefore not precisely those we had looked for, but we

had

undoubtedly proved our contention that Desolation Island is in two

halves, united

only by the 160 yards covered by the portage on the Lobo Isthmus.

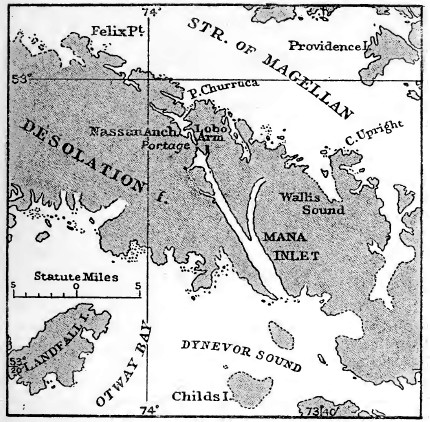

FIG. 13. — MANA

INLET

A

knowledge of the existence of this channel, connecting the Pacific

Ocean with

the Magellan Straits, might be of high importance to the crew of a

vessel lost

to the south of Cape Pillar, when making for the entrance to the

Straits.

Instead of trying to round that Cape against wind at sea, her boats

should run

to the southward until the entrance to the inlet is reached; they can

then

enter the Magellan Straits without difficulty at Port Churruca. With

the

consent of the Royal Geographical Society, it has been christened "Mana Inlet." 1

The next

morning, December 1st, we left Churruca with a fair wind, so that the

engine

was only needed at the beginning and end of the day; but the weather

was

drizzling and unpleasant, so that we could see little of Cape Pillar,2

where

the Magellan Straits enter the Pacific Ocean. Our own course was up the

waterways between the western coast of Patagonia and the islands which

lie off

the coast. It is a route that is little taken, owing to the dangers of

navigation. Not only is much of it uncharted and unsurveyed, but it is

also

unlighted, and its passage is excluded by the ordinary insurance terms

of

merchant ships; they consequently pass out at once into the open sea at

Cape

Pillar. We turned north at Smyth's Channel, the first of these

waterways, and

made such good progress that, instead of anchoring as we had intended

at

Burgoyne's Bay, we were able to reach Otter Bay. It is situated amid a

mass of

islands, and the sad vision of a ship with her back broken emphasised

the need

for caution. The general character of the Patagonian Channels is of the

same

nature as the Magellan Straits, but particularly beautiful views of the

Andes

are obtained to the eastward. The next day Mount Burney was an

impressive

spectacle, although only glimpses of the top could be obtained through

fleeting

mists; and the glistening heights of the Sarmiento Cordillera came out

clear

and strong. We anchored that night at Occasion Cove on Piazzi Island;

and on

Saturday, December 13th, had a twelve hours' run, using the engine all

the way.

Here there was a succession of comparatively monotonous hills and

mountains, so

absolutely rounded by ice action as to give the impression of apple

dumplings

made for giants. The lines show always, as would be expected, that the

ice-flow

has been from the south. Later a ravine on Esperanza Island was

particularly

remarkable; its mysterious windings, which it would have been a joy to

explore,

were alternately hidden by driving cloud or radiant with gleams of sun.

Glimpses up Peel Inlet gave pleasant views, and two snowy peaks on

Hanover

Island, unnamed as usual, were absorbing our attention when we turned

into

Latitude Cove.

On December

14th the landscape was absolutely grey and colourless, so that Guia

Narrows

were not seen to advantage. Later the channel was wider and the

possibility of

sailing debated, but abandoned in view of the head wind. We had been

struck

with the absence of life and fewness of birds, but we now saw some

albatrosses.

In slacking away the anchor preparatory to

letting go in Tom Bay, in a depth stated to be seventeen fathoms, it

hit an

uncharted rock at eleven fathoms. It was still raining as we left Tom

Bay, but

when we turned up Brassey Pass, which lies off the regular channel, the

clouds

began to lift, and Hastings Fiord and Charrua Bay were grand beyond

description. From time to time the mists rose for an instant, and

revealed the

immediate presence of reach beyond reach of wooded precipices; or a

dark summit

appeared without warning, towering overhead at so great a height that,

severed

by cloud from its base, it seemed scarcely to belong to the earth. Then

as

suddenly the whole panorama was cut off, and we were alone once more

with a

grey sea and sky.

FIG. 14 — CANOE

CORDUROY PORTAGE BETWEEN PORT

CHURRUCA AND MANA INLET.

FIG. 15. —

PATAGONIAN WATERWAYS.

Showing water near the land smoothed by growing kelp.

As we

approached Charrua, we caught sight among the trees on a neighbouring

island of

something which was both white and nebulous; it might, of course, be

only an

isolated wreath of mist, but after watching it for a while we came to

the

conclusion that it was undoubtedly a cloud of smoke. Our hopes of

seeing

Indians, which had grown faint, began to revive. As soon as we were

anchored,

orders were given that immediately after dinner the launch should be

ready for

us to inspect what we hoped might prove a camping-ground. This turned

out to be

unnecessary, as the neighbours made the first call. In an hour's time

S. came

to inform me that two canoes were approaching full of natives "just

like

the picture-books," whereon the anthropologists felt inclined to adapt

the

words of the immortal Snark-hunters and exclaim:

"We

have sailed many weeks, we have sailed many days,

Seven days to the week I allow,

But

an Indian on whom we might lovingly gaze

We have never beheld until now."

The crew,

however, were fully convinced that the hour had arrived when they would

have to

defend themselves against ferocious savages. They had been carefully

primed in

every detail by disciples of Ananias at Buenos Aires, and by the

bloodcurdling

accounts of a certain mariner named Slocum, who claimed to have sailed

the

Straits single-handed and to have protected himself from native

onslaught by

means of tin-tacks sprinkled on the deck of his ship. The canoes were

about 23

feet in length, with beam of 4 to 6 feet and a depth of 2 feet. Six

Indians

were in one and seven in the other; all were young with the exception

of one

older man, and each boat contained a mother and baby. Their skins were

a dark

olive, which was relieved in the case of the women and children by a

beautiful

tinge of pink in the cheeks, and they had very good teeth. Their hair

was long

and straight, and a fillet was habitually worn round the brow; the top

was cut à la brosse, giving the impression of a

monk's tonsure which had been allowed to grow. The height of the men

was about

5 feet 4 inches. Most of the party were clad in old European garments,

but a

few wore capes of skins, and some seemed still more at home in a state

of

nature. They had brought nothing for sale, but begged for biscuits and

old

clothes. I parted with a wrench from a useful piece of calico, in the

interests

of one of the infants, which was still in its primitive condition; it

was

accepted, but with a howl of derision, which I humbly felt was well

merited

when it was seen that the rival baby was already wrapped in an old

waistcoat

given by the cook. One of the Indians talked a little Spanish, and was

understood to say he was a Christian.

After

dealing with them for a while we offered to tow them home, an offer

readily

understood, and accepted without hesitation. It was a strange

procession amid

weird surroundings; the sun had shown signs of coming out, but had

thought

better of it and retreated, and we made our way over a grey sea,

between

half-obscure cliffs in drizzling rain, taking keen note of our route

for fear

of losing our way back. Truly we seemed to have reached the uttermost

ends of

the earth. The lead was taken by that recent product of civilisation a

motor-launch, containing our two selves and our Glasgow socialist

engineer; then at the end of a rope came the

dinghy, to be used for landing, the broad back of one of our Devonshire

seamen

making a marked object as he stood up in it to superintend the towing

of the

craft behind. The two canoes followed, full of these most primitive

specimens

of humanity, while the rear was brought up by a seal, which swam after

us for a

mile or so, putting up its head at intervals to gaze curiously at the

scene. S.

had brought his gun, and as we approached the camp thought it well to

shoot a

sea-bird, for the double reason of showing that he was armed and giving

a

present to our new friends. The encampment was situated in a little

cove, and

nothing could have been more picturesque. In front was a shingly beach,

on

which the two canoes were presently drawn up, flanked by low rocks

covered with

bright seaweed. In the background was a mass of trees, shrubs, and

creepers,

which almost concealed two wigwams, from one of which had issued the

smoke

which attracted our notice (fig. 16).

We

returned next morning to photograph and study the scene. The size of

the

shelters, or tents, was about 12 feet by 9 feet, with a height of some

5 feet.

They were formed by a framework of rods set up in oval form, the tops

of which

were brought together and interwoven, and strengthened by rods laid

horizontally and tied in place: the opening was at the side and towards

the

sea. Over this structure seals' skins were thrown, which kept in place

by their

own weight, as the encampments are always made in sheltered positions

in dense

forests. With the exception that they do not possess a ridge-pole, the

tents,

which are always the same in size and make, closely resemble those of

English

gipsies, the skins taking the place of the blankets used by those

people. No

attempt was made to level the floor, the fire was in the middle, and in

one the

sole occupant was a naked sprawling baby, who occupied the place of

honour on

the floor beside it. In some of the old encampments, which we saw

subsequently

, there were as many as six huts, but it was doubtful if they had all

been occupied

at the same time. The middens are outside and generally near the door.

Some of

the Indians were quite friendly, but others were not very cordial, the

old

women in particular making it clear to the men of the party that their

presence

was not welcome. The old man, whose picture appears (fig. 17), was

apparently

the patriarch of the party, and quite amiable, though he firmly

declined to

part with his symbol of authority in the shape of his club; in order to

keep

him quiet while his photograph was taken he was fed on biscuits, which

he was

taught to catch after the manner of a pet dog. The staff of life is

mussels and

limpets, and we saw in addition small quantities of berries. A lump of

seal fat

weighing perhaps 10 lb. was being gnawed like an apple, and a portion

was

offered to our party. The dogs are smooth-haired black-and-tan

terriers, like

small heavy lurchers; they are, it is said, taught to assist their

masters in

the catching of fish.3

The

company presently showed signs of unusual activity, and began to shift

camp;

the movement was not connected, as far as we could tell, with our

presence,

and, judging by the odour of the place, the time for it had certainly

arrived.

It was interesting to see their chattels brought down one by one to the

canoes.

Amongst them were receptacles resembling large pillboxes, about 12

inches

across, made of birchwood, which was split thin and sewn with tendons.

In these

were kept running nooses made of whalebone for capturing wild geese,

and also harpoon-lines

cut out of sealskin: at one extremity of these last was a barbed head

made of

bone; this head, when in use, fits into the extremity of a long wooden

shaft,

to which it is then attached by the leather thong. The possessions

included an

adze-like tool for making canoes, the use of which was demonstrated,

and

resembled that of a plane; also an awl about 2 inches long, in form

like a

dumb-bell, with a protruding spike at one end. There were small pots

made of

birch bark for baling the boats, and some European axes. We did not see

any

form of cooking utensil. When all the objects, including the sealskin

coverings

of the huts, had been stowed in the canoes, the company all embarked

and rowed

off towards the open sea.

On

leaving Charrua and returning to the main channel we obtained

magnificent views

of the Andes. Penguin Inlet leading inland opened up a marvellous

panorama of

snowy peaks, which can be visible only on a clear day such as we were

fortunate

in possessing; this range received at least one vote, in the final

comparing of

notes, as to the most beautiful thing seen between Punta Arenas and the

Gulf of

Pefias. A white line across the water showed where the ice terminated,

while

small pieces which reached the main channel, looked, as they floated

past us,

like stray water-lilies on the surface of the sea. We anchored at Ring

Dove

Inlet, and went on next day through Chasm Reach, where the channel is

only from

five hundred to a thousand yards in width. Our expectations, which had

been

greatly raised, were on the whole disappointed, but here again no doubt

it was

a question of lighting; the usually gloomy gorge was illuminated with

the full

radiance of the summer sun, leaving nothing to the imagination.

Chasm

Reach leads into Indian Reach, in which sea, mountain, and sky formed a

perfect

harmony in varying shades of blue, with touches of white from high

snow-clad

peaks. Suddenly, in the middle of this vista, as if made to fit into

the scene,

appeared a dark Indian canoe with its living freight, evidently making

for the

vessel. We stopped the engine, threw them a line, and towed them to our

anchorage in Eden Harbour. The weather had suddenly become much warmer,

and the

thermometer in the saloon had now risen to the comfortable but scarcely

excessive height of 64°; the crew of the canoe, however, were so

overcome with

the heat that they spent the time pouring what must have been very

chilly

sea-water over their naked bodies.4

FIG. 16. —

ENCAMPMENT OF THE PATAGONIAN

INDIANS, BRASSEY PASS.

FIG. 17. — INDIANS

OF BRASSEY PASS.

FIG. 18. — CANOE IN

INDIAN REACH.

The party

was conducted by two young men; a very old woman without a stitch of

clothing

crouched in the bow; while in the middle of the boat, in the midst of

ashes, mussel-shells,

and other debris, a charming girl mother sat in graceful attitude. She

was,

perhaps, seventeen, and wore an old coat draped round her waist, while

her

baby, of some eighteen months, in the attire of nature, occupied itself

from

time to time in trying to stand on its ten toes. A younger girl of

about

fourteen sat demurely in the stern with her folded arms resting on a

paddle

which lay athwart the canoe, beneath which two shapely little brown

legs were

just visible. Her rich colouring, and the faded green drapery which she

wore,

made against the dark background of the canoe a perfect study for an

artist,

but the moment an attempt was made to photograph her she hid her face

in her

hands. The party was completed by a couple of dogs and a family of fat

tan

puppies, who were held up from time to time, but whether for our

admiration or

purchase was not evident.

The

belongings were similar to those seen at the encampment and there were

also

baskets on board. The young mother had a necklace which looked like a

charm,

and therefore particularly excited our desires: in response to our

gestures she

handed to us a similar one worn by the baby, which was duly paid for in

matches. When we were still unsatisfied she beckoned to the young girl

to sell

hers, but stuck steadfastly to her own, till finally a mixed bribe of

matches

and biscuits proved too much, and the cherished ornament passed into

our

keeping. The young men readily came on deck of the yacht, but the women

were

obviously frightened, and kept saying mala,

mala in spite of our efforts to reassure them. After we had cast

anchor,

the party went with our crew to show them the best spot in which to

shoot the

net, and on their return ran up the square sail of their canoe, the

halyard

passing over a mast like a small clothes-prop with a Y-shaped

extremity, got

out their paddles, and vanished downstream.

At Eden

Harbour a wreck was lying in mid-stream, where she had evidently struck

on an

uncharted rock when trying to enter the bay, a danger from which no

possible

foresight can guard those who go down to the sea in ships. English

Narrows,

which was next reached, is considered the most difficult piece of

navigation in

the channels: a small island lies in the middle of the fairway, leaving

only a

narrow passage on either side, down which, under certain conditions,

the tide

runs at a terrific rate. It was exciting, as the yacht approached her

course

between the island and opposing cliff which are separated by only some

360

yards, to hear Mr. Ritchie ask Mr. Gillam to take the helm himself, and

the

latter give the order to "stand by the anchor" in case of mishap; but

we had hit it off correctly at slack water and got through without

difficulty.

From there our route passed through Messier Channel, which has all the

appearance of a broad processional avenue, out of which we presently

turned to

the right and found ourselves in Connor Cove. The harbour terminates in

a

precipitous gorge, down which a little river makes its way into the

inlet. We

endeavoured to row up it, but could not get further than 100 or 200

yards; even

that distance was achieved with difficulty, owing to the number of

fallen trees

which lay picturesquely across the stream.

The plant

life, which had always been most beautiful, became even more glorious

with the

rather milder climate, which we had now reached. When the trees were

stunted it

was from lack of soil, not from atmospheric conditions. Tree-ferns

abounded,

and flowering plants wandered up moss-grown stems; among the most

beautiful of

these blooms were one with a red bell and another one which almost

resembled a

snowdrop.5 The impression of the luxuriant mêlé

was rather that of a tropical forest than of an almost

Antarctic world, while the intrusion of rocks and falling water added

peculiar

charm. Butterflies were seen occasionally, and sometimes humming-birds.

Since our

detention at Churruca we had been favoured with unvarying good fortune,

and the

crew were beginning to say that thirteen, which we had counted on board

since

Mr. Corry joined us, was proving our lucky number. Now, however, our

fate

changed; twice did we set forth from this harbour only to be obliged to

return

and start afresh, till we began to feel that getting under way from

Connor Cove

was rapidly becoming a habit. On the first occasion the weather became

so thick

that in the opinion of our Navigator it was not safe to proceed: the

second

time the wind was against us. We tried both engine and sails, but

though we

could make a certain amount of headway under either it was obviously

impossible, at the rate of progression, to reach the next haven before

nightfall; when, therefore, we were already half-way to our goal we

once more

found it necessary to turn round. It was peculiarly tantalising to

reflect that

there were, in all probability, numerous little creeks on the way in

which we

could have sheltered for the night, but as none of them had been

surveyed there

was no alternative but to go back to our previous anchorage. Residence

there

had the redeeming point that it proved an excellent fishing-ground. On

each of

the three nights the trammel was shot at a short distance from the spot

where

the stream entered the bay, and we obtained in all some 200 mullet.

They formed

an acceptable change of diet, and those not immediately needed were

salted.

From that time till we left the channels we were never without fresh

fish,

catching, in addition to mullet, bream, gurnet, and a kind of whiting;

they

formed part of the menu at every meal, till the more ribald persons

suggested

that they themselves would shortly begin to swim.

Our third

effort to leave Connor Cove was crowned with greater success, and we

safely

reached Island Harbour, which, as its name suggests, is sheltered by

outlying

islands. This bay and the neighbouring anchorage of Hale Cove are the

last two

havens in the channels before the Gulf of Pefias is reached, and in

either of

them a vessel can lie with comfort and await suitable weather for

putting out

to sea. It is essential for a sailing vessel to obtain a fair wind, for

not

only has she to clear the gulf, but must, for the sake of safety, put

200 miles

between herself and the land; otherwise, should a westerly gale arise,

she

might be driven back on to the inhospitable Patagonian coast. In Island

Harbour

we filled our tanks, adorned the ship for'ard with drying clothes and

fish, and

for three days waited in readiness to set forth. At the end of that

time it was

still impossible to leave the channels, but we decided to move on the

short

distance to Hale Cove, which we reached on December 24th. Christmas Eve

was

spent by three of our party, Mr. Ritchie, Mr. Corry, and Mr. Gillam, on

a small

rock "taking stars" till 2 a.m. The rock, which had been selected at

low tide, grew by degrees unexpectedly small, and to keep carefully

balanced on

a diminishing platform out of reach of the rising water, while at the

same time

being continuously bitten by insects, was, they ruefully felt, to make

scientific observations under difficulties. On Christmas Day it poured

without

intermission, but it was a peaceful if not an exciting day. It is, I

believe,

the correct thing to give the menu on these occasions: the following

was ours.

Schooner

Yacht MANA, R.C.C.