| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

II THE VOYAGE TO SOUTH AMERICA A Gale at Sea — Madeira — Canary Islands — Cape Verde Islands — Across the Atlantic. The first

day in open ocean was spent in shaking down; on going on deck before

turning in

it was found to be a clear starlight night, and the man at the wheel

prophesied

smooth things. It was a case of — "A

little ship was on the sea.

It was a pretty sight, It sailed along so pleasantly. And all was calm and bright." But,

alas! the storm did soon begin to rise; by morning we were in troubled

waters,

and by noon we were battened down and hove to. We had given up all idea

of

making progress and were riding out the gale as best we might. All the

saloon

party were more or less laid low, including Mr. Ritchie, for the first

time in

his life. The steward was not seen for two days; and if it had not been

that

the under-steward, who shall be known as "Luke," rose to the

occasion, the state of affairs would have been somewhat serious. He not

only

contrived to satisfy the appetites of the crew, which were subsequently

said to

have been abnormally good, but also staggered round, with black hands

and a

tousled head, ministering with tea and bovril to our frailer needs. The

engineer, a landsman, was too incapacitated to do any work, and doubt

arose as to

whether we should not be left without electric light. More alarming was

the

fact that the place smelt badly of paraffin, arousing anxiety as to the

effect

the excessive rolling of the ship might have had on our carefully

tested tanks

and barrels; happily the odour proved to be due merely to a temporary

overflow

in the engine-room. We now

found the disadvantage of having abandoned, owing to our various

delays, the

trial runs in home waters which had at one time been planned. The

skylights,

which would have been adequate for ordinary yachting — which has been

described

as "going round and round the Isle of Wight" — proved unequal to the

work expected of Mana, and the truth

appeared of a dark saying of the Board of Trade surveyor that

"skylights

were not ventilation." Not only could they of course not be raised in

bad

weather, but those which, like mine, were arranged to open, admitted

the sea to

an unpleasant degree; such an amount of water had to be conveyed by

means of

dripping towels into canvas baths that it seemed at one time as if the

Atlantic

would be perceptibly emptier. When in the midst of the gale night fell

on the

lonely ship the sensation was eerie; every now and then the persistent

rolling,

which threw from side to side of the berth those fortunate enough to be

below,

was interrupted by a resounding crash in the darkness as a big wave

broke

against the vessel's side, followed by the rushing surge and gurgle of

the

water as it poured in a volume over the deck above. Then the hubbub

entirely

ceased, and for a perceptible time the vessel lay perfectly still in

the trough

of the wave, like a human creature dazed by a sudden blow, after a

second or

two to begin again her weary tossing. I wondered, as I lay there, which

was the

more weird experience, this night or one spent in camp in East Africa

with no

palisade, in a district swarming with lions, and again recalled the

philosophy

of one of our Swahili boys. "Frightened? No, he eats me, he does not

eat

me; it is all the will of Allah." By

morning the worst was over, and it was a comfort to hear Mr. Gillam

singing

cheerfully something about "In the Bay of Biscay O," a performance he

varied with anathemas on the seasick steward. When I was able to get on

deck,

the waves were still descending on us — if not the proverbial

mountains, at any

rate hills high, looking as if they must certainly overwhelm us. It was

wonderful to see, what later I took for granted, how the yacht rose to

each,

taking it as it were in her stride. It was reported to have been a

"full

gale, a hurricane, as bad as could be, with dangerous cross seas"; but

the

little vessel had proved herself a splendid sea-going boat, and "had

ridden it out like a duck." For the next little while I can

only say in the words of the poet, “It was not night, it was not day";

neither the clothes people wore, nor the food they took, nor their

times of

downsitting and uprising had anything to do with the hours of light and

darkness. By Saturday, however, the weather was better, meals were

established,

and things generally more civilised. We had another bad gale somewhere

in the

latitude of Finisterre, being hove to for thirty hours, but were

subsequently

very little troubled with seasickness. The second Sunday out, April

6th, we

experienced a short interlude of calm, and I discovered that not only

does a

sailing ship not travel in bad weather, but that when it is really

beautifully

smooth she also has a bad habit of declining to go. Anyway, we held our

first

service, and "O God, our help" went, if not in Westminster Abbey

form, at any rate quite creditably. Mr.

Ritchie had decided to take two sides of a triangle, first west and

then south,

rather than run any risk of being blown on to Ushant or Finisterre; a

precaution which, in view of the proved powers of the boat to hold her

own

against a head wind, he subsequently thought to have been unnecessary.

After we

left the English shores we only saw two vessels till we were within

sight of

Madeira, and some of our Brixham men, who had never been far from their

native

shores or away from their fishing fleet, were much impressed with the

size and

loneliness of the ocean. “It was astonishing," said Light, "that

there could be so much water without any land or ships," and he

expressed

an undisguised desire for "more company." Somehow

or other we had all come to the conclusion that we would put into

Madeira,

instead of going straight through to Las Palmas, for which we had

cleared from

Falmouth. The first land which we sighted was the outlying island of

the group,

Porto Santo. This was appropriate on a voyage to the New World, as

Columbus

resided there with his father-in-law, who was governor of the place;

and it is

said that from his observations there of driftwood, and other

indications, he

first conceived the idea of the land across the waters, to which he

made his

famous voyage in 1492. Our mate entertained us with a tale of how he

had been

shipwrecked on Porto Santo, the yacht on which he was serving having

overrun

her reckonings as she approached it from the west; happily all on board

were

able to escape. The wind fell after we made the group, so that we did

not get

into the harbour of Funchal for another thirty-six hours, and then only

with

the help of the motor. It was most enjoyable cruising along the coast

of Madeira,

watching the great mountains, woods, ravines, and nestling villages, at

whose

existence the passengers on the deck of a Union-Castle liner can only

vaguely

guess. The day was Sunday, April 13th, and later it became a matter of

remark

how frequently we hit off this day of the week for getting into

harbour, a most

inconvenient one from the point of view of making the necessary

arrangements.

As we entered, a Portuguese liner, coming out of Funchal, dipped its

flag in

greeting to our blue ensign; out came the harbour-master's tug to show

us where

to take up our position, down went the anchor with a comfortable

rattle, and so

ended the first stage of our journey. The

voyage had taken eighteen days, and averaged about sixty miles a day,

as

against the hundred miles on which we had calculated, and which later

we

sometimes exceeded. A man who crosses the ocean in a powerful

steam-vessel, as

one who travels by land in an express train, undoubtedly gains in

speed, but he

loses much else. He misses a thousand beauties, he has no contact with

Nature,

no sense of the exultation which comes from progress won step by step

by

putting forth his own powers to bend hers to his will. The late veteran

seaman

Lord Brassey is reported to have said that "when once an engine is put

into a ship the charm of the sea is gone." All through our voyage also

there was a fascinating sense of having put back the hands of time.

This was

the route and these in the main the conditions under which our

ancestors, the

early Empire builders, travelled to India; later we were on the track

of Drake,

Anson, and others. Some of Drake's ships were apparently about the size

of Mana.1 The world has been

shrinking of late, and to return to a simpler day is to restore much of

its

size and dignity.  FIG. 2 — PORTO SANTO. MADEIRA Madeira was settled by the

Portuguese early

in the fifteenth century. With the exception of an interlude in the

Napoleonic

wars, when it was taken by England, it has ever since been a possession

of that

country. GRAND CANARY The Canary group consists

of some nine

islands, of which the most important are Teneriffe and Grand Canary.

They have

been known from the earliest times, but European sovereignty did not

begin till

1402, and it was the end of the century before all the islands became

subject

to the crown of Castile. This prolonged warfare was due to the very

brave

resistance offered by the original inhabitants, known as Guanches.

These very

interesting people, who are of Berber extraction, withstood the

Spaniards till

1483, and the name of Grand Canary is said to have been obtained from

their

stubborn defence. The final defeat of the natives was largely due to

the terror

inspired by their first sight of a body of cavalry which the Spaniards

had

landed on the island. The Guanches of Teneriffe held out till 1496. The

Canaries were thus subdued just in time to become a steppingstone to

the New

World. The horses of the cavalry were carried to America, and formed

part of

the stock from which sprang the wild American mustang. The

aspect of our new harbour, Puerto de la Luz by name, was somewhat

depressing.

On its south side is the mainland of the island, which consists of

sandhills,

behind which are bleak, arid-looking mountains, whose summits during

the whole

of our three weeks' stay were continuously veiled in mist. The west

side is

formed by the promontory of Isleta, which would be an island save that

it is

connected with Grand Canary by a sand isthmus washed up by the sea,

much after

the manner that Gibraltar is united to the Spanish mainland. The

remainder of

the protection for the harbour consists of artificial breakwaters. The

only

spot on which the eye rests with pleasure is a distant view of a

cluster of

houses, above which rises a cathedral; this is the capital. Las Palmas,

which

lies two or three miles to the south. The effect made on the newcomer,

especially after leaving luxuriant Madeira, is that of having been

transported

into the heart of Africa. The port,

if not attractive, is at any rate prosperous. The Canaries are still a

stepping-stone to the New World, and in accordance with modern

requirements

have turned into a great coaling station. In Puerto de la Luz six or

seven

different firms compete for the work. The British Consul, Major

Swanston, gave

us a most interesting account of his duties during the South African

War in

revictualling the transports which called here. Mention should not be

omitted

of the delightful new institute of the British and Foreign Sailors'

Society,

with billiard-room, reading-room, and arranged concerts, to which our

men were

very glad to resort; but indeed we met similar kind provision in so

many ports

that it seems invidious to particularise. This was

my first experience of life in a foreign port as "stewardess," for

our stay at Madeira was only an interlude. To passengers on a mail

steamer the

time so spent is generally concerned with changing into shore clothes,

and

making up parties for dinner on land to avoid the exigencies of

coaling. To

those in charge of a small boat its aspect is very different . Much of

it is

not a time of leisure, but to be an acting member of a British ship in

a

foreign port is distinctly exhilarating. It brings with it a sense both

of

being a humble representative of one's own nationality, and also of

belonging

to the great busy fraternity of the sea. First, as land is approached,

comes

the running up of the ensign and burgee; then the making of the ship's

number,

as the signal station is passed, which will in due course be reported

to

Lloyds; next follows the entry into port, and the awaiting of the

harbour-master,

on whose fiat it hangs where the vessel shall take up her berth. He is

succeeded by doctor and customs officer to examine the ship's papers;

and all

these are matters not for some mysterious personages with gold braid,

but of

personal interest. As soon

as the yacht is safely berthed the Master goes on shore to visit the

consul,

and obtain the longed-for letters and newspapers. In the food

department the

important question of food at once arises. My hope had always been that

we

should have found a steward capable of taking over this responsibility,

but

though we had various changes, and paid the highest wages, we were

never able

to get one sufficiently reliable, and the work therefore fell on the

Stewardess. We at first used to go on shore and cater personally, which

is no

doubt the most satisfactory method, but in view of the time involved we

subsequently relied on the "ships' chandlers," who are universal

providers, to be found in all ports of any size, and who will bring

fresh

stores to the ship daily. A very careful examination and comparison of

prices

is necessary, for one of the annoying parts of owning a boat is that

even the

smallest yacht-owner is considered fair game for extortion and

dishonest

dealing. The variation in the cost of commodities in different harbours

requires a very elastic mind on the part of the housekeeper, both as to

menus

in port and purchases for the next stage of the voyage. It puts an

extremely

practical interest into the list of exports, which formed so dreary a

part of

geography as taught in one's own childhood. At Las Palmas prices were

much as

in pre-war England; at our next port, in Cape Verde Islands, the best

meat was

sixpence a pound, and fish sufficient for four cost threepence, but the

cost of

bread was high. At Rio de Janeiro and elsewhere in South America,

though most

things were ruinous, we obtained enough coffee at very reasonable

prices to

carry us home; while in Buenos Aires, with mutton at fourpence a pound,

it was

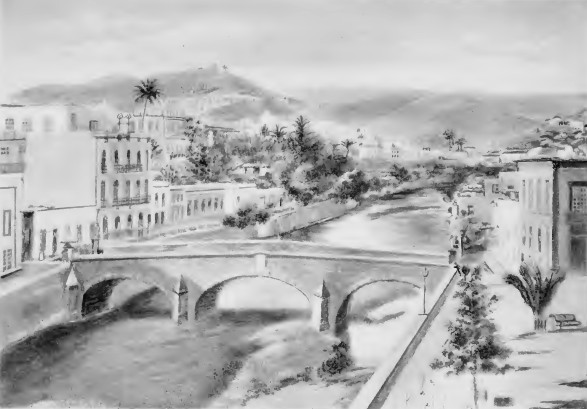

a matter of regret that the hold was not twice as large.  FIG. 3. LAS PALMAS, GRAND CANARY. We were

glad when we were at last able to see something of the country. If the

harbour

of Luz is not beautiful, the road from it into Las Palmas is still less

so. It

runs between the sea and arid sandhills, and abounds in ruts and dust;

as there

is also no street lighting, "the rates," as S. remarked, "can

hardly be high." Half-way along this road there stand, for no very

obvious

reason, the English Church and Club, also a good hotel, the Santa

Catalina,

belonging to a steamship company; otherwise it is bordered by poor and

unattractive houses of stucco, the inhabitants of which seem

permanently seated

at the windows to watch the passers-by. Happily the distance is

traversed by

means of trams, owned by a company with English capital, which run

frequently

between the port and the city and do the journey in twenty minutes. Las

Palmas itself is not unpicturesque. Its main feature is a stony

river-bed,

which runs down the centre of the city and is spanned by various

bridges; it

was empty when we saw it, but is no doubt at times, even in this

waterless

land, filled with a raging, boiling current from the mountains. In the

principal square, opposite the cathedral, is the museum, which contains

an

admirable anthropological collection, concerned mostly with relics of

the

Guanches. When we were there the city was gay with bunting and grand

stands for

a fiesta, in celebration of the

anniversary of the union of the islands with the crown of Castile; a

flying

man, a carnival, and an outdoor cinema entertainment were among the

chief

excitements. At one of the hotels we discussed politics with the

waiter, who

was a native of the island. He had been in England, but never in Spain;

nevertheless, he seemed in touch with the situation in the ruling

country. There

would, he declared, be great changes in Spain in the next fifteen

years. The

King did his best in difficult circumstances, but anti-clerical feeling

was too

strong to allow of the continuation of the present state of things. In

Grand

Canary there was, he said, the same feeling as in Spain against the

constant

exactions of the Church. The women were still devout, but you might go

into any

village and talk against the Church and meet with sympathy from the

men. He

himself was a socialist, and as such "had no country”; countries were

for

rich people who had something belonging to them, something to lose; for

those

who had to work all countries were the same." He only lived in Canary,

he

said, because his people were there. We pointed out that the bond with

one's

own people was precisely what made one country home and not another,

but the

argument fell flat. The great

charm of the island lies in the mountainous character of the interior

region.

Three roads radiate from the capital, one along the coast to the north,

another

to the south, and the third inland. Along all these it is necessary to

travel

some distance before points of interest are reached, and we were at the

disadvantage of never being able to be more than a night or two away

from the

ship without returning to see how the work on board was progressing. On

all the

main routes are run motor-buses, which are chiefly characterised by

indications

of impending dissolution, and inspire awe by the rapidity with which

they turn

corners without any preliminary easing down. The natives, however,

appeared to

think that the accidents were not unreasonably numerous. In addition

to motors there are local "coaches" drawn by horses, after the manner

of covered wagonettes; they will no doubt be gradually superseded by

the

motors, but still command considerable custom. Both types of vehicles

are

delightfully vague in the hours which they keep, being just as likely

to start

too soon as too late, thus presupposing an indefinite amount of time

for the

passengers to spend at the starting-place. Our first

expedition was by the inland or middle road, which winds up by the

bleak

hillside till it reaches a beautiful and attractive country. To those

unaccustomed to such latitudes, it comes as a surprise to see fertility

increasing instead of diminishing with elevation, due to the more

constant rain

among the hills. Monte and Santa Brigida may be said to be residential

neighbourhoods and have comfortable hotels and boarding-houses. There

are two

principal sights to be visited from there. One is the village of

Atalaya, which

consists of a zone of cave dwellings, almost encircling the summit of a

dome-shaped

hill. The eminence falls away on two sides to a deep ravine, over which

it

commands magnificent views, and is connected with the adjacent hills by

a

narrow coll. The rock is of consolidated volcanic tuff, in which the

dwellings

are excavated. The fronts of the houses abut on the pathway, which is

about

four feet wide, and are unequally placed, following the contour of the

ground. Each

dwelling consists of two apartments, both about twelve feet square,

with

rounded angles and a domed roof, the surface of the walls shows the

chisel-marks. The front apartment is used as a bed-sitting-room, the

back one

as a store; and in some cases a lean-to outhouse has been built of

blocks of

the same material, in which cooking is done and the goats kept. Doors

and window-sashes

are inserted into the solid stone. Both dwellings and surroundings are

beautifully clean and neat; the first one exhibited we imagined to be a

“show"

apartment, till others proved equally neat and orderly. Flowers were

planted in

crannies of the rock and around the doors and windows, being carefully

tended

and watered. The industry of the village is making pots by hand without

a

wheel, the sand being obtained in one direction and the clay in

another: the

shapes coincide in several instances with those taken from native

burial-grounds and now to be seen in the museum at Las Palmas. The

occasion of

our visit was unfortunately a fiesta,

and regular work was not going on: an old lady, however, made us a

model pot in

a few minutes; it was fashioned out of one piece of clay, with the

addition of

a little extra material if necessary: the pottery is unglazed. Various

specimens of the art were obtained by the Expedition and are now in the

Pitt-Rivers Museum at Oxford. About

half a mile from these troglodyte abodes, and adjoining the coll, is an

extraordinarily fine specimen of an extinct crater or caldero.

Its walls are almost vertical and unclad by vegetation:

about two-thirds of the circumference is igneous rock, and the rest

black

volcanic ash, which exhibits the stratification in the most marked

manner. The

crater is about 1,000 feet deep, the floor is flat and dry, and the

visitor looks

down on a house at the bottom and cultivated fields. We

returned to Mana for a night or two,

and then made an expedition by motor along the north road, sleeping at

the

picturesque village of Fergas, and from thence by mule over the

beautiful

mountain-track to Santa Brigida. We changed animals en

route, and the price asked for a fresh beast was outrageous. We

were prepared under the circumstances to pay it, when the portly lady

of the

inn, who was obviously "a character," beckoned us mysteriously round a

corner, and, though we had scarcely two words of any language in

common, gave

us emphatically to understand that we were on no account to be so

swindled, she

would see we got another. This, however, was not accomplished for

another hour,

with the result that the last part of the journey was traversed in

total

darkness, and the lights of the hotel were very welcome. Mana being still in the hands of work-people,

we

made our next way by the south road to the town of Telde, near which is

a

mountain known as Montana de las Cuatro Puertas, where are a wonderful

series

of caves connected with the Guanches. The road from Las Palmas skirts

the

seacoast for a large part of the way, being frequently cut into the

cliff-face

and in one place passing through a tunnel: the town lies on the lowland

not far

from the sea. We arrived late in the afternoon, and endeavoured to make

a

bargain for rooms with the burly landlord of the rather humble little

inn. As

difficulties supervened a man who spoke a little English was called in

to act

as interpreter. He turned out to be a vendor of ice-creams who had

visited

London, and to make the acquaintance of the exponent of such a trade in

his

native surroundings was naturally a most thrilling experience. He

expressed a

great desire to return to that land of wealth, England, though his

knowledge of

our language was so extremely limited he had obviously, when there,

associated

principally with his own countrymen. We went

for a stroll before dark, noticing the system of irrigation: the water

is

preserved in large tanks, from which it is distributed in all

directions by

small channels, and so valuable is it that these conduits are in many

cases

made of stone faced with Portland cement. They are now, however, in

some

instances being replaced by iron pipes, which have naturally the merit

of

saving loss by evaporation. Canary is a land where the owner of a

spring has

literally a gold-mine. This is the most celebrated district for

oranges. After

our evening meal we joined the company in the central plaza

of the little town. The moon shone down through the trees;

young men sat and smoked, and young girls, wearing white mantillas,

strolled

about in companies of four or five, chatting gaily. The elders belonged

to the

village club, which opened on to the square; it was confined seemingly

to one

room, of which the whole space was occupied by a billiard-table; this,

however,

was immaterial, as the company spent a large part of the time in the plaza, an arrangement which doubtless

had the merit of saving house rent. A little way down a side street the

light

streamed from the inn windows. Nearer at hand the church stood out

against the

sky; it was May, the month of the Virgin Mary, and a special service in

her

honour had just concluded. One felt a momentary expectation that Faust

and

Marguerite or other friends from stage-land would appear on the scene;

they may

of course have been there unrecognised by us.  FIG. 4. — PORTO GRANDE, ST. VINCENT, CAPE VERDE ISLANDS. We

discovered after much trouble that a motor-bus ran through the village

early

next morning, passing close to the mountain which we had come to visit,

and

could drop us on the way. We passed a fairly comfortable night, though

not

undiversified by suspicions that our beds were occupied by earlier

denizens;

and had just begun breakfast when the bus appeared, some time before

the earliest

hour specified. We had to tear down and catch it, leaving the meal

barely

tasted; the kind attendant following us and pressing into our hand the

deserted

fried fish done up in a piece of newspaper. Such hurry, however, proved

to be

quite unnecessary, as we had not got beyond the precincts of the small

town

before the vehicle came to an unpremeditated stop, through the fan

which cools

the radiator having broken. We waited half an hour or so in company

with our fellow-passengers,

who appeared stolidly resigned, and then, as there seemed no obvious

prospect

of continuing our journey, grew restless. Here again the ice-cream man

acted as deus ex machina: he was standing

about with the crowd which had assembled, blowing a horn at intervals,

and

distributing ices not infrequently to small infants, whose fond mammas

provided

the requisite penny; he told us he generally made a sum equal to about

one-and-sixpence

a day in this manner. Grasping our difficulty, he delivered an

impassioned

address on our need to the assembled multitude, which after further

delay

resulted in the appearance of a wagonette and mules. The Montana de las

Cuatro

Puertas rises out of comparatively level ground near the coast and

commands

magnificent views. The top is honeycombed with caves, and one towards

the north

has the four entrances from which the mountain takes its name. It is

said to

have been the site of funeral rites of the inhabitants. The place is

both

impressive and interesting, and would well repay more careful study

than the

superficial view which was all it was possible for us to give it. We

decided to return to Las Palmas in the local coach, as we had

previously found

travelling by this means both cheap and quite comfortable. This time,

however,

our luck was otherwise. The vehicle could have reasonably held eleven,

but one

passenger after another joined it along the route, one newcomer was

constrained

to find a seat on the pole, another stood on the step, and so forth,

till we

numbered twenty, of all ages and sexes. The day was hot, but the

good-natured

greeting, almost welcome, which was given to each arrival by the

original

passengers made us hesitate to show the feelings which consumed us. The

sentiments of the horses are not recorded, but we gathered that they

were more

analogous to our own. All on Mana was at length

ready. There were the

usual good-byes and parting duties: the bank had to be visited, all

bills

settled, and letters posted. Last of all a bill of health had to be

obtained

from the representative of the country to which the ship was bound,

certifying

that she came from a clean port and that all on board were well. We left

Las Palmas on Saturday, May 10th: the trade wind was still with us, the

weather

delightful, and we did the distance to St. Vincent, Cape Verde Islands,

in

seven days. We had heard nothing but evil of it. “An impossible place;"

"another Aden;" "a mere cinder-heap." It was therefore a

pleasant surprise to find ourselves in a most beautiful harbour. Rugged

mountains of imposing height rise on three sides of the bay, Porto

Grande, and

the fourth is protected by the long high coastline of the neighbouring

island,

San Antonio. Standing out in the entrance of the bay is the conical

Birds'

Rock, looking as if designed by nature for the lighthouse it carries.

The

colouring is indescribable: all the nearer mountains are what can only

be

termed a glowing red, which, as distance increases, softens into

heliotrope. On

the edge of the bay and at the foot of the eastern hills lies the town

of

Mindello. A building law, made with the object of avoiding glare,

forbids any

house to be painted white, and the resulting colour-washes, red,

yellow, and

blue, if sometimes a little crude, tone on the whole well into the

landscape. If beauty

of form and strange weird colouring are the first things which strike

the

newcomer to St. Vincent, the next, it must be admitted, is the

marvellous

bleakness of the place. Hillsides and mountains stand out bare and

rugged,

without showing, on a cursory inspection at any rate, the least sign of

vegetation. One of the characteristics also of the place is the

constant

tearing wind. During the whole of our visit of some ten days we were

never able

to find a day when it was calm enough for Mrs. Taylor, the wife of the

British

Consul, to face the short passage from the harbour and visit Mana. This wind is purely local and a

short distance off dies away. How, one is inclined to ask, can it be

possible

for English men and women to endure life in a tropical glare, with a

perpetual

wind without any trees, any grass, any green on which to rest the eye?

And yet

we found over and over again that, though the comer from greener worlds

is at

first unhappy and restless in St. Vincent, those who had been there

some time

found life pleasant and enjoyable and had no desire to exchange it. There are

several coaling and other English firms, and local society rejoices in

as many

as thirty English ladies. The cable company has over a hundred

employees, of

whom the greater number are English. The unmarried members of the staff

live

together in the station, each having a bed-sitting-room and dining in a

common

hall. There is an English chaplain, and also a Baptist minister, who is

the

proprietor of the principal shop. The chaplain had the experience,

which

everyone must have felt would happen some time to someone, of being

carried off

involuntarily on an ocean-going steamer. He was saying good-bye to

friends,

missed the warning bell, and before he knew was en route

for a port in South America, to which he had duly to

proceed. For recreation St. Vincent possesses a tennis-court and

cricket-field:

the last is in a particularly arid spot some distance from the town,

which is

however already planned out on paper by the authorities with streets

and houses

for prospective needs; in the design the pitch is left vacant and named

in

Portuguese "Game of Cricket," the remainder of the field being filled

in anticipation with a grove of trees. Some of

the residents have villas among the hills or by one of the scarce

oases. We

made an excursion to one of these last resorts which is a famed

beauty-spot,

and found it a narrow gulch between two mountains, with a little stream

and a

few unhappy vegetables and woebegone trees. It was difficult to

imagine, while

traversing the road along one hillside after another, each covered with

nothing

but rocks and rubble, on what the few animals subsisted; it was

remarked that

the milk could not need sterilising, as the cows fed only on stones.

The rains

occur in August, after which the hills are covered with a small green

plant. We

were told that some of the valleys higher up are comparatively

fruitful, and

certainly it is possible to obtain vegetables at a not unreasonable

price. The

women who live in the hills carry back quite usually, after a shopping

expedition, loads of seventy to eighty pounds for a distance of perhaps

three

miles, with a rise of 900 feet, making the whole journey in two and a

half

hours. The

British Consul, Captain Taylor, R.N., has with much enterprise

established a

body of Boy Scouts among the youthful inhabitants. An attractive member

of the

corps, wearing a becoming and sensible uniform, accompanied us as guide

on two

occasions, when we made excursions on the island, giving the whole

afternoon to

us. He declined to accept any remuneration, as it was against the

principles of

his order to be paid for doing a good turn. Other youthful natives are

less

useful and more grasping. One small imp, with a swarthy complexion and

head

like an overgrown radish, became our constant follower. The

acquaintance began

one day when S. was carrying a large biscuit-tin from the post office,

in which

some goods had just arrived from England: he followed him down the

pier,

beseeching, “Oh, Captain Biscuit-Tin, give me one penny." Every time

after

this, when S. went on shore for business or pleasure, “Biscuit-Tin," as

we

in our turn named the boy, was there awaiting him. Once, in stepping

out of the

boat on to the rusty iron ladder of the jetty, his toe almost caught on

a small

round head as it emerged from the water uttering the cry, "Oh, Captain,

where is that penny?” A crowd had surrounded the landing-stage, so the

boy had

dived into the water as the easiest way of approach. He expressed the

desire to

come with us to Buenos Aires, undeterred by the information which S.

gravely

gave him that "all the boys on board were beaten every day, with an

extra

beating on Saturday." The avocation which he proposed to fill was that

of

cook's boy, as he "would have much to eat." He followed us for the

whole of one expedition, eventually obtaining "that penny" as we

shoved off from the pier for the last time, an hour before sailing. He

clapped

it into his cheek, as a monkey does a nut, and held out his hand to me

for

another; but I was already in the boat, and a coin was not forthcoming;

so that

the last which we saw of "Biscuit-Tin" he was still demanding "one

penny." We

brought away from St. Vincent a permanent addition to our party, a

Portuguese

negro of fine build, by name Bartolomeo Rosa. The rest of the crew

accepted his

companionship without hesitation and naturally christened him "Tony."

Later we found, with sympathy, that he was wearing goloshes, in a

temperature

when most of the party were only too happy to go shoeless, because

Light, who

had more particularly taken him under his wing, said "the sight of his

black feet puts me off my food." Rosa remained with us to the end of

the

voyage. He learnt English slowly, and would never have risen to the

rank of

A.B., but was always quiet, steady, and dependable. He drew but little

of his

wages, and had therefore a considerable sum standing to his credit when

we returned

to Southampton. He proposed, he said, to go back to his old mother at

St.

Vincent and there set up with his earnings as a trader. He would get a

shop,

stock it, and marry a wife, and she would attend to the customers,

while he

would sit outside the door on the head of a barrel and smoke. When it

was

suggested that such a course would inevitably end in drink, he added a

boat to

the programme, in which he would sometimes go out and catch fish. We were

detained at St. Vincent awaiting the arrival of a spare piece of

machinery, and

occupied the time by watering the yacht at the bay of Tarafel in the

island of

San Antonio. A stream from the high ground there finds its way to the

sea, and

supplies the water for the town of Mindello. The lower part of its

banks are

fertile, forming a beautiful, if small, spot of verdure amid the arid

surroundings. Light, with the green hills of Devonshire in mind,

remarked, “It

is very nice, ma'am, what there is of it — only there is so little." When we

brought up, the men went into the shallow water and shot the trammel in

order

to obtain some fresh fish. This brought on board an elderly gentleman,

Seńior

Martinez, the official in charge of the place, who was not unnaturally

indignant at what he imagined to be a foreign fishing vessel at work in

territorial waters. We were able to explain matters, and were much

interested

in making his acquaintance. He had never visited England, but spoke

English

well, kept it up by means of magazines, and was greatly delighted with

the gift

of some literature. He welcomed us as the first English yacht which had

been

there since the visit of the Sunbeam

in 1876, of which he spoke as if it had been yesterday. Having

got our package from England, we finally quitted the friendly harbour

of Porto

Grande on Thursday afternoon. May 29th, sailing forth once more, this

time to

cross the Atlantic, with the little shiver and thrill which it still

gave some

of us when we committed our bodies to the deep for a long and lonely

voyage,

even with every hope of a resurrection on the other side of the ocean.

After we

sighted St. Jago, the capital of the Cape Verde group, on the following

day, we

saw no trace of human life for thirteen days; so that if mischance

occurred

there was nothing and no one to help in all the blue sea and sky. The

self-sufficiency needed by those who go down to the sea in ships is

almost

appalling. Instead

of making direct for Pernambuco, we steered first of all due south,

carrying

with us the north-east trade, in order to cross the Doldrums to the

best

advantage, and catch the south-east trade as soon as possible on the

other

side. The calm belt may be expected just north of the Equator, but its

position

varies with climatic conditions, and it was therefore a matter of

excitement to

know how long we should keep the wind. In the opinion of our

authorities it

might leave us on Sunday and could not be with us beyond Tuesday. The

engineer,

whose duty had so far been light, had been chaffingly warned by the

rest of the

crew that his turn would come in the tropics, when he would have to

work below

for twenty-four hours on end. On Sunday

S. gave orders that the engine was to be started by day or night,

whenever the

officer in command of the watch thought it necessary; but still the

north-east

trade held good. On Monday all hands were at work stowing the mainsail,

for as

soon as the calm came the squalls were expected which are typical of

that part

of the world. On Tuesday evening, when according to calculation we

should have

been out of its zone, we were still travelling before the wind, and we

began to

congratulate ourselves with trembling, that our passage would be more

rapid

than we had ventured to hope. All Wednesday, however, the breeze was

very

light, and we kept our finger on its pulse as on that of a sick man. By

Thursday it had faded and had died away, the sails hung slack, the gear

rattled

noisily, the motor was run. The air was hot, damp, and sticky, with

heavy

squalls, and the nights were trying. It is impossible to sleep on the

deck of a

small sailing ship, with so many strings about and someone always

pulling at

something, so we roamed from our berths to cabin floors and saloon

settees and

back again, “seeking rest and finding none." The thermometer in the

cabin

never throughout the voyage rose to more than eighty-three degrees,

but, as is

well known, it is humidity and lack of air rather than the absolute

height of

temperature which determine comfort. Friday afternoon increased air

roused our

hopes; but, alas! it soon subsided, and during the night we again

relied on the

engine. Saturday morning was still squally, with a grey sea and heavy

showers,

but there was really a slight breeze. Was it or was it not, we asked

under our

breath, the beginning of the new wind? By ten o'clock there was no

longer room

for doubt: the south-east trade was blowing strong and full, and the

ship, like

some living creature suddenly let loose, bounding away before it for

very joy.

It felt like nothing so much as a wonderful gallop over ridge and

furrow after

a long and anxious wait at covert-side.  FIG 5. — A GROUP ON DECK. A. Light; Steward; B. Rosa; Under-Steward; C. Jeffery; W. Marks; F. Preston (Mate); H. J. Gillam (Sailing-master). We

crossed the Equator in glorious weather about 9 p.m. on Monday, June

9th. None

of the forecastle had been over before: Father Neptune did not feel

equal to

visiting them, but some addition to the fare was much appreciated. I

was the

doyen of the party, with now seven crossings to my credit. Flying-fish

came at

times on board from the shoals through which we passed, “Portuguese

men-of-war" floated by the ship, and schools of porpoises played about

her

bows. The wind on the whole stood our friend for the rest of the way,

and

during the last week of the voyage the average daily run was 147 miles

on our

course, the highest record being 179 miles on June 14th. We continued,

however,

to have squalls and rain at intervals, as we were running into the

rainy

season; and it was through a mist that on Sunday, June 15th, after a

passage of

seventeen days, we strained our eyes to see the South American coast.

It dawned

at last on our view, a flat and somewhat low land; then came into sight

the

towers and coconut palms of Pernambuco, and the passage of the Atlantic

was

accomplished. 1 The Pelican, or Golden Hinde, was 120 tons; the Elizabeth

80 tons, and three smaller ships were 50, 30, and 12 tons respectively.

The

crews all told were 160 men and boys. — Froude's English

Seamen, p. 112. |