| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

Modern Restraints It has often been asserted

by foreign observers that the real power in Japan is exercised not from above,

but from below. There is some truth in this assertion, but not all the truth: the

conditions are much too complex to be covered by any general statement. What

cannot be gainsaid is that superior authority has always been more or less

restrained by tendencies to resistance from below.... At no time in Japanese

history, for example, do the peasants appear to have been left without recourse

against excessive oppression, notwithstanding all the humiliating regulations

imposed on their existence. They were suffered to frame their own village-laws,

to estimate the possible amount of their tax payments, and to make protest through

official channels against unmerciful exaction. They were made to pay as much

as they could; but they were not reduced to bankruptcy or starvation; and their

holdings were mostly secured to them by laws forbidding the sale or alienation

of family property. Such was at least the general rule. There were, however,

wicked daimyō, who treated their farmers with extreme cruelty, and found ways

to prevent complaints or protests from reaching the higher authorities. The

almost invariable result of such tyranny was revolt; and the tyrant was then

made responsible for the disorder, and punished. Though denied in theory, the

right of the peasant to rebel against oppression was respected in practice; the

revolt was punished, but the oppressor was likewise punished. Daimyō were

obliged to reckon with their farmers in regard to any fresh imposition of taxes

or forced labour. We also find that although heimin were made subject to the military class, it was possible for

artizans and commercial folk to form, in the great cities, strong associations by

which military tyranny was kept in check. Everywhere the reverential deference

of the common people to authority, as exercised in usual directions, seems to

have been accompanied by an extraordinary readiness to defy authority exercised

in other directions. It may seem strange that a

society in which religion and government, ethics and custom, were practically identical,

should furnish striking examples of resistance to authority. But the religious

fact itself supplies the explanation. From the earliest period there was firmly

established, in the popular mind, the conviction that implicit obedience to

authority was the universal duty under all ordinary circumstances. But with

this conviction there was united another, that resistance to authority

(excepting the sacred authority of the Supreme Ruler) was equally a duty under

extraordinary circumstances. And these seemingly opposed convictions were not really

inconsistent. So long as rule followed precedent, so long as its commands,

however harsh, did not conflict with sentiment and tradition, that rule was

regarded as religious, and there was absolute submission. But when rulers

presumed to break with ethical usage, in a spirit of reckless cruelty or

greed, then the people might feel it a religious obligation to resist with

all the zeal of voluntary martyrdom. The danger-line for every form of local

tyranny was departure from precedent. Even the conduct of regents and princes

was much restrained by the common opinion of their retainers, and by the

knowledge that certain kinds of arbitrary conduct were likely to provoke

assassination. Deference to the sentiment

of vassals and retainers was from ancient time a necessary policy with Japanese

rulers, not merely because of the peril involved by needless oppression, but

much more because of the recognition that duties are well performed only when

subordinates feel assured that their efforts will be fairly considered, and

that sudden needless changes will not be made to their disadvantage. This old policy

still characterizes Japanese administration; and the deference of high

authority to collective opinion astonishes and puzzles the foreign observer. He

perceives only that the conservative power of sentiment, as exercised by groups

of subordinates, remains successfully opposed to those conditions of discipline

which we think indispensable to social progress. Just as in Old Japan the ruler

of a district was held responsible for the behaviour of his subjects, so

to-day, in New Japan, every official in charge of a department is held responsible

for the smooth working of its routine. But this does not mean that he is

responsible only for the efficiency of a service: it means that he is held

responsible likewise for failure to satisfy the wishes of his subordinates, or

at least the majority of his subordinates. If this majority be displeased with

their minister, governor, president, manager, chief, or director, the fact is

considered proof of administrative incompetency.... Perhaps educational circles

afford the most curious examples of this old idea of responsibility. A

student-revolt is commonly supposed to mean, not that the students are

intractable, but that the superintendent or teacher does not know his business.

Thus the principal of a college, the director of a school, holds his office

only on the condition that his rule gives satisfaction to a majority of the

students. In the higher government institutions, each professor or lecturer is

made responsible for the success of his lectures. No matter how great may be

his ability in other directions, the official instructor, unable to make

himself liked by his pupils, will be got rid of in short order unless some

powerful protectors interfere on his behalf. The efforts of the man will never

be judged (officially) by any accepted standard of excellence, never

estimated by their intrinsic worth; they will be considered only according to

their direct effect upon the average of minds.1 Almost everywhere

this antique system of responsibility is maintained. A minister of state is by

public sentiment made responsible not only for the results of his

administration, but likewise for any scandals or troubles that may occur in his

department, independently of the question whether he could or could not have

prevented them. To a considerable degree, therefore, it is true that the ultimate

power is below. The highest official is not able with impunity to impose his

personal will in certain directions; and, for the time being, it is probably

better that his powers are thus restrained. From above downwards

through all the grades of society, the same system of responsibility, and the same

restraints upon individual exercise of will, persist under varying forms. The

conditions within the household differ but little in this regard from the conditions

in a government department: no householder, for example, can impose his will,

beyond certain fixed limits, even upon his own servants or dependents. Neither

for love nor money can a good servant be induced to break with traditional custom;

and the old opinion, that the value of a servant is proved by such

inflexibility, has been justified by the experience of centuries. Popular sentiment

remains conservative; and the apparent zeal for superficial innovation affords

no indication of the real order of existence. Fashions and formalities, house-interiors

and street-vistas, habits and methods, and all the outer aspects of life are

changed; but the old regimentation of society persists under all these

surface-shiftings; and the national character remains little affected by all

the transformations of Meiji. The second kind of coercion

to which the individual is subjected the communal, or communistic seems

likely to prove mischievous in the near future, as it signifies practical suppression

of the right to compete.... The everyday life of any Japanese city offers

numberless suggestions of the manner in which the masses continue to think and

to act by groups. But no more familiar and forcible illustration of the fact

can be cited than that which is furnished by the code of the kurumaya or jinrikisha-men. According to

its terms, one runner must not attempt to pass by another going in the same

direction. Exceptions have been made, grudgingly, in favour of runners in private

employ, men selected for strength and speed, who are expected to use their

physical powers to the utmost. But among the tens of thousands of public kurumaya, it is the rule that a young

and active man must not pass by an old -and feeble man, nor even by a

needlessly slow and lazy man. To take advantage of one's own superior energy,

so as to force competition, is an offence against the calling, and certain to

be resented. You engage a good runner, whom you order to make all speed: he springs

away splendidly, and keeps up the pace until he happens to overtake some weak

or lazy puller, who seems to be moving as slowly as the gait permits.

Therewith, instead of bounding by, your man drops immediately behind the

slow-going vehicle, and slackens his pace almost to a walk. For half an hour,

or more, you may be thus delayed by the regulation which obliges the strong and

swift to wait for the weak and slow. An angry appeal is made to the runner who

dares to pass another; and the idea behind the words might be thus expressed:

"You know that you are breaking the rule, that you are acting to the

disadvantage of your comrades! This is a hard calling; and our lives would be

made harder than they are, if there were no rules to prevent selfish

competition!" Of course there is no thought of the consequences of such

rules to business interests at large.... Now it is not unjust to say that this

moral code of the kurumaya

exemplifies an unwritten law which has been always imposed, in varying forms,

upon every class of workers in Japan: You must not try, without special authorization,

to pass your fellows."... La

carriθre est ouverte aux talents mais la concurrence est defendue! Of course the modern

communal restraint upon free competition represents the survival and extension of

that altruistic spirit which ruled the ancient society, not the mere

continuance of any fixed custom. In feudal times there were no kurumaya; but all craftsmen and all

labourers formed guilds or companies; and the discipline maintained by those guilds

or companies prohibited competition as undertaken for merely personal

advantage. Similar or nearly similar forms of organization are maintained by

artizans and labourers to-day; and the relation of any outside employer to

skilled labour is regulated, by the guild or company, in the old communistic manner....

Let us suppose, for instance, that you wish to have a good house built. For

that undertaking, you will have to deal with a very intelligent class of

skilled labour; for the Japanese house-carpenter may be ranked with the artist

almost as much as with the artizan. You may apply to a building-company; but,

as a general rule, you will do better by applying to a master-carpenter, who combines

in himself the functions of architect, contractor, and builder. In any event

you cannot select and hire workmen: guild-regulations forbid. You can only make

your contract; and the master-carpenter, when his plans have been approved,

will undertake all the rest, purchase and transport of material, hire of

carpenters, plasterers, tilers, mat-makers, screen-fitters, brass-workers,

stone-cutters, locksmiths, and glaziers. For each master-carpenter represents

much more than his own craft-guild: he has his clients in every trade related to

house-building and house-furnishing; and you must not dream of trying to interfere

with his claims and privileges.... He builds your house according to contract;

but that is only the beginning of the relation. You have really made with him

an agreement which you must not break, without good and sufficient reason, for

the rest of your life. Whatever afterwards may happen to any part of your

house, walls, floor, ceiling, roof, foundation, you must arrange for

repairs with him, never with anybody else. Should the roof leak, for instance, you

must not send for the nearest tiler or tinsmith; if the plaster cracks, you

must not send for a plasterer. The man who built your house holds himself

responsible for its condition; and he is jealous of that responsibility: none

but he has the right to send for the plasterer, the roofer, the tinsmith. If

you interfere with that right, you may have some unpleasant surprises. If you

make appeal to the law against that right, you will find that you can get no

carpenter, tiler, or plasterer to work for you at any terms. Compromise is

always possible; but the guilds will resent a needless appeal to the law. And

after all, these craft-guilds are usually faithful performers, and well worth conciliating.

Or take the occupation of

landscape-gardening. You want a pretty garden; and you hire a professional gardener

who comes to you well recommended. He makes the garden; and you pay his price.

But your gardener really represents a company; and by engaging him it is

understood that either he, or some other member of the gardeners' corporation

to which he belongs, will continue to take care of your garden as long as you

own it. At each season he will pay your garden a visit, and put everything to rights:

he will clip the hedges, prune the fruit trees, repair the fences, train the

climbing-plants, look after the flowers, putting up paper awnings to protect

delicate shrubs from the sun during the hot season, or making little tents of

straw to shelter them in time of frost; he will do a hundred useful and

ingenious things for a very small remuneration. You cannot dismiss him,

however, without good reason, and hire another gardener to take his place. No

other gardener would serve you at any price, unless assured that the original

relation had been dissolved by mutual consent. If you have just cause for

complaint, the matter can be settled through arbitration; and the guild will

see that you have no further trouble. But you cannot dismiss your gardener

without cause, merely to engage another. The above examples will

suffice to show the character of the old communistic organization which is yet

maintained in a hundred forms. This communism suppressed competition, except as

between groups; but it insured good work, and secured easy conditions for the

workman. It was the best system possible in those ages of isolation when there

was no such thing as want, and when the population, for yet undetermined

causes, appears to have remained always below the numerical level at which

serious pressure begins.... Another interesting survival is represented by

existing conditions of apprenticeship and service, conditions which also originated

in the patriarchal organization, and imposed other kinds of restraint upon

competition. Under the old regime service was, for the most part, unsalaried.

Boys taken into a commercial house to learn the business, or apprentices bound to

a master-workman, were boarded, lodged, clothed, and even educated by their

patron, with whom they might hope to pass the rest of their lives. But they were

not paid wages until they had learned the business or the trade of their

employer, and were fully capable of managing a business or a workshop of their

own. To a considerable degree these conditions still prevail in commercial

centres, though the merchant or patron seldom now finds it necessary to send

his clerk or apprentice to school. Many of the great commercial houses pay

salaries only to men of great experience: other employιs are only trained and

cared for until their term of service ends, when the most clever among them

will be reengaged as experts, and the others helped to start in business for

themselves. In like manner the apprentice to a trade, when his term expires, may

be reengaged by his master as a hired journeyman, or helped to find permanent

employ elsewhere. These paternal and filial relations between employer and

employed have helped to make life pleasant and labour cheerful; and the quality

of all industrial production must suffer much when they disappear. Even in private domestic

service the patriarchal system still prevails to a degree that is little

imagined; and this subject deserves more than a passing mention. I refer

especially to female service. The maid-servant, according to the old custom, is

not primarily responsible to her employers, but to her own family; and the

terms of her service must be arranged with her family, who pledge themselves for

their daughter's good behaviour. As a general rule, a nice girl does not seek

domestic service for the sake of the wages (which it is now the custom to pay),

nor for the sake of a living, but chiefly to prepare herself for marriage; and

this preparation is desired as much in the hope of doing credit to her own

family, as in the hope of better fitting herself for membership in the family

of her future husband. The best servants are country girls; and they are

sometimes put out to service very young. Parents are careful about choosing the

family into which their daughter thus enters: they particularly desire that the

house be one in which a girl can learn nice ways, therefore a house in which

things are ordered according to the old etiquette. A good girl expects to be

treated rather as a helper than as a hireling, to be kindly considered, and

trusted, and liked. In an old-fashioned household the maid is indeed so treated;

and the relation is not a brief one from three to five years being the term

of service usually agreed upon. But when a girl is taken into service at the

age of eleven or twelve, she will probably remain for eight or ten years. Besides

wages, she is entitled to receive from her employers the gift of a dress, twice

every year, besides other necessary articles of clothing; and she is entitled

also to a certain number of holidays. Such wages, or presents in money, as she

receives, should enable her to provide herself, by degrees, with a good

wardrobe. Except in the event of some extraordinary misfortune, her parents

will make no claim upon her wages; but she remains subject to them; and when

she is called home to be married, she must go. During the period of her

service, the services of her family are also at the disposal of her employers.

Even if the mistress or master desire no recognition of the interest taken in

the girl, some recognition will certainly be made. If the servant be a farmer's

daughter, it is probable that gifts of vegetables, fruits, or fruit trees,

garden-plants or other country products, will be sent to the house at intervals

fixed by custom; if the parents belong to the artizan-class, it is likely

that some creditable example of handicraft will be presented as a token of

gratitude. The gratitude of the parents is not for the wages or the dresses

given to their daughter, but for the practical education she receives, and for

the moral and material care taken of her, as a temporarily adopted child of the

house. The employers may reciprocate such attentions on the part of the parents

by contributing to the girl's wedding outfit. The relation, it will be observed,

is entirely between families, not between individuals; and it is a permanent

relation. Such a relation, in feudal ages, might continue through many

generations. The patriarchal conditions

which these survivals exemplify helped to make existence easy and happy. Only

from a modern point of view is it possible to criticise them. The worst that

can be said about them is that their moral value was chiefly conservative, and

that they tended to repress effort in new directions. But where they still

endure, Japanese life keeps something of its ancient charm; and where they have

disappeared, that charm has vanished forever. There remains to be

considered a third form of restraint, that exercised upon the individual by official

authority. This also presents us with various survivals, which have their

bright as well as their dark aspects. We have seen that the individual

has been legally freed from most of the obligations imposed by the ancient law.

He is no longer obliged to follow a particular occupation; he is able to travel;

he is at liberty to marry into a higher or a lower class than his own; he is

not even forbidden to change his religion; he can do a great many things at

his own risk. But where the law leaves him free, the family and the community

do not; and the persistence of old sentiment and custom nullifies many of the rights

legally conferred. Precisely in the same way, his relations to higher authority

are still controlled by traditions which maintain, in despite of constitutional

law, many of the ancient restraints, and not a little of the ancient coercion.

In theory any man of great talent and energy may rise, from rank to rank, up to

the highest positions. But as private life is still controlled to no small

degree by the old communism, so public life is yet controlled by survivals of

class or clan despotism. The chances for ability to rise without assistance, to

win its way to rank and power, are extraordinarily small; since to contend

alone against an opposition that thinks by groups, and acts by masses, must be

almost hopeless. Only commercial or industrial life now offers really fair

opportunities to capable men. The few talented persons of humble origin who do

succeed in official directions owe their success chiefly to party-help or clan-patronage:

in order to force any recognition of personal ability, group must be opposed to

group, Alone, no man is likely to accomplish anything by mere force of

competition, outside of trade or commerce.... It is true, of course, that

individual talent must in every country encounter many forms of opposition. It

is likewise true that the malevolence of envy and the brutalities of

class-prejudice have their sociological worth: they help to make it impossible

for any but the most gifted to win and to keep success. But in Japan the

peculiar constitution of society lends excessive power to social intrigues

directed against obscure ability, and makes them highly injurious to the

interests of the nation; for at no previous time in her history has Japan needed,

so much as now, the best capacities of her best men, irrespective of class or

condition. But all this was inevitable

in the period of reconstruction. More significant is the fact that in no single

department of its multitudinous service does the Government yet offer

substantial reward to rising merit. No matter how well a man may strive to win

Government approbation, he must strive for little more than honour and the bare

means of existence. The costliest efforts are no more highly paid in proportion

to their worth than the cheapest; the most invaluable services are scarcely

better recognized than those most easily dispensed with or replaced. (There

have been some remarkable exceptions: I am stating only the general rule.) By

extraordinary energy, patience, and cleverness, one may reach, with class-help,

some position which in Europe would assure comfort as well as honour; but the

emoluments of such a position in Japan will scarcely cover the actual cost of

living. Whether in the army or in the navy, in the departments of justice, of

education, of communications, or of home affairs, the differences in

remuneration nowhere represent the differences in capacity and responsibility.

To rise from grade to grade signifies pecuniarily almost nothing, for the

expenses of each higher position augment out of all proportion to the salaries

fixed by law. The general rule has been to exact everywhere the greatest

possible amount of service for the least possible amount of pay.2

Any one unacquainted with the social history of the country might suppose that

the policy of the Government toward its employιs consisted in substituting

empty honours for material advantages. But the truth is that the Government has

simply maintained, under modern forms, the ancient feudal condition of service,

service in exchange for the means of simple but honourable living. In feudal

times the farmer was expected to pay all that he could pay for the right to

exist; the artist or artizan was expected to content himself with the good

fortune of having a distinguished patron; even the ordinary samurai were

supplied with barely more than the necessary by their liege-lords. To receive

considerably more than the necessary signified extraordinary favour; and the

gift was usually accompanied by promotion. But although the same policy is yet

successfully maintained by Government, under the modem system of money-payments,

the conditions everywhere, outside of commercial life, are incomparably harder

than in feudal times. Then the poorest samurai was secured against want, and not

liable to be dismissed from his post without fault. Then the teacher received

no salary; but the respect of the community and the gratitude of his pupils

assured him of the means to live respectably. Then the artizans were patronized

by great lords who vied with each other in the encouragement of humble genius.

They might expect the genius to be satisfied with merely nominal payment, so

far as money was concerned; but they secured him against want or discomfort,

allowed him ample leisure to perfect his work, made him happy in the certainty

that his best would be prized and praised. But now that the cost of living has

tripled or quadrupled, even the artist and the artizan have small encouragement

to do their best: cheap rapid work is replacing the beautiful leisurely work of

the old days; and the best traditions of the crafts are doomed to perish. It

cannot even be said that the state of the agricultural classes to-day is

happier or better than in the time when a farmer's land could not legally be

taken from him. And as the cost of life continues always to increase, it is

evident that at no distant time, the present patient order of things will become

impossible. To many it would seem that

a wise government must recognize the impracticability of indefinitely maintaining

its present demand for self-sacrifice, must perceive the necessity of

encouraging talent, inviting fair competition, and making the prizes of life

large enough to stimulate healthy egoism. But it is possible that the

Government has been acting more wisely than outward appearances would indicate.

Several years ago a Japanese official made in my presence this curious

observation: Our Government does not wish to encourage competition beyond the

necessary. The people are not prepared for it; and if it were strongly

encouraged, the worst side of character would come to the surface. How far

this statement really expressed any policy I do not know. But every one is

aware that free competition can be made as cruel and as pitiless as war, though

we are apt to forget what experience must have been undergone before Occidental

free competition could become as comparatively merciful as it is. Among a

people trained for centuries to regard all selfish competition as criminal, and

all profit-seeking despicable, any sudden stimulation of effort for purely

personal advantage might well be impolitic. Evidence as to how little the

nation was prepared, twelve or thirteen years ago, for Western forms of free

government, has been furnished by the history of the earlier district-elections

and of the first parliamentary sessions. There was really no personal enmity in

those furious election-contests, which cost so many lives; there was scarcely

any personal antagonism in those parliamentary debates of which the violence

astonished strangers. The political struggles were not really between individuals,

but between clan-interests, or party-interests; and the devoted followers of

each clan or party understood the new politics only as a new kind of war, a

war of loyalty to be fought for the leader's sake, a war not to be interfered

with by any abstract notions of right or justice. Suppose that a people have

been always accustomed to think of loyalty in relation to persons rather than

to principles, loyalty as involving the duty of self-sacrifice regardless of

consequence, it is obvious that the first experiments of such a people with

parliamentary government will not reveal any comprehension of fair play in the

Western sense. Eventually that comprehension may come; but it will not come

quickly. And if you can persuade such a people that in other matters every man

has a right to act according to his own convictions, and for his own advantage,

independently of any group to which he may belong, the immediate result will

not be fortunate, because the sense of individual moral responsibility has

not yet been sufficiently cultivated outside of the group-relation. The probable truth is that

the strength of the government up to the present time has been chiefly due to

the conservation of ancient methods, and to the survival of the ancient spirit

of reverential submission. Later on, no doubt, great changes will have to be

made; meanwhile, much must be bravely endured. Perhaps the future history of

modern civilization will hold record of nothing more touching than the patient

heroism of those myriads of Japanese patriots, content to accept, under legal conditions

of freedom,, the official servitude of feudal days, satisfied to give their

talent., their strength, their utmost effort, their lives, for the simple

privilege of obeying a government that still accepts all sacrifices in the

feudal spirit as a matter of course, as a national duty. And as a national

duty, indeed, the sacrifices are made. All know that Japan is in danger,

between the terrible friendship of England and the terrible enmity of Russia,

that she is poor, that the cost of maintaining her armaments is straining her

resources, that it is everybody's duty to be content with as little as

possible. So the complaints are not many.... Nor has the simple obedience of

the nation at large been less touching, especially, perhaps, as regards the

imperial order to acquire Western knowledge, to learn Western languages, to

imitate Western ways. Only those who have lived in Japan during or before the early

nineties are qualified to speak of the loyal eagerness that made

self-destruction by over-study a common form of death, the passionate

obedience that impelled even children to ruin their health in the effort to

master tasks too difficult for their little minds (tasks devised by

well-meaning advisers with no knowledge of Far-Eastern psychology), and the

strange courage of persistence in periods of earthquake and conflagration, when

boys and girls used the tiles of their ruined homes for school-slates, and bits

of fallen plaster for pencils. What tragedies I might relate even of the higher

educational life of universities! of fine brains giving way under pressure of

work beyond the capacity of the average European student, of triumphs won in the

teeth of death, of strange farewells from pupils in the time of the dreaded

examinations, as when one said to me: "Sir, I am very much afraid that my

paper is bad, because I came out of the hospital to make it there is

something the matter with my heart." (His diploma was placed in his hands

scarcely an hour before he died.)... And all this striving striving not only

against difficulties of study, but in most cases against difficulties of

poverty, and underfeeding, and discomfort has been only for duty, and the

means to live. To estimate the Japanese student by his errors, his failures, his

incapacity to comprehend sentiments and ideas alien to the experience of his

race, is the mistake of the shallow: to judge him rightly one must have learned

to know the silent moral heroism of which he is capable. 1 Unjust as this policy must appear to the Western reader (a policy which

certainly presupposes ethical conditions very different from our own), it was

probably at one time the best possible under the new order. Considering the extraordinary

changes suddenly made in the educational system, it will be obvious that a

teacher's immediate value was likely twenty years ago to depend on his

ability to make his teaching attractive. If he attempted to teach either above

or below the average capacity of his pupils, or if he made his instruction

unpalatable to minds greedy for new knowledge, but innocent as to method, his

inexperience could be corrected by the will of his class. 2 Salaries of judges range from £70 to £500 per annum, the latter

figure representing the highest possible emolument. The highest salary allowed

to a Japanese professor in the imperial universities has been fixed at £120.

The wages of employιs in the postal departments is barely sufficient to meet

the cost of living. The police are paid from £1 to £1 10s. per month, according

to locality} and the average pay of school-teachers is yet lower (being 9 yen 50 sen, or about 19s. per

month), many receiving less than 7s.

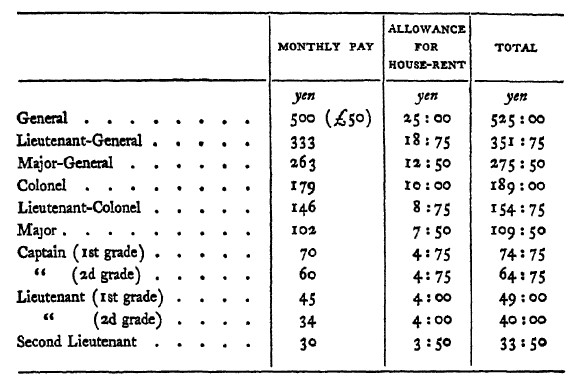

a month. Readers may be interested

in the following table of army-payments (1904):  When these rates of pay were fixed, about twenty years ago, house-rent was cheap: a good house could be rented anywhere at 3 yen or 4 yen per month. To-day in Tōkyō an officer can scarcely rent even a very small house at less than 18 yen or 20 yen; and prices of food-stuffs have tripled. Yet there have been very few complaints. Officers whose pay will not allow them to rent houses hire rooms wherever they can. Many suffer hardship; but all are proud of the privilege of serving, and no one dreams of resigning. |