1999-2002

(Return to Web Text-ures)

Click Here to return to

Dutch Cousins

Content Page

Click Here to return to

the previous section

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

CHAPTER II.

THE AMERICAN COUSIN

Any one who saw the twins on their way to school one morning soon after the visit of Mynheer Van der Veer would know that something unusual had happened, for they were both talking away at once, in a most excited manner. Little Dutch children are usually very quiet, when compared to the children of most other countries, though they are full of fun, in a quiet sort of a way, when they want to be.

"Oh, Pieter," Wilhelmina was saying, "to think that we have a cousin coming to see us from across the seas!"

"I wonder if he can talk Dutch; if he can't we will have to speak English, so you had better see to it that you have a better English lesson than you did yesterday," said Pieter, who was rather vain of his own English.

There is nothing strange in hearing little Dutch children speak English, French, or German, for they are taught all three languages in their schools; and even very little children can say some words of English or German.

"It is well for you to talk," said Wilhelmina, feeling hurt. "English is not hard for you to learn; as for me, I can learn my German lesson in half the time that you can."

"Ah well! the German is more like our own Dutch language," said Pieter, soothingly, for the twins were never "at outs" for long at a time. "You will soon learn English from our new cousin from America. Listen! there is the school-bell ringing now," and away they clattered in their wooden shoes to the schoolhouse.

Yesterday there had been a solemn meeting in the Joost home. You must know that it was an important occasion, because they all met in the "show-room." The "domine" (as the Dutch call their clergymen) had been invited, and the schoolmaster, too, and they all sat around and sipped brandied cherries and coffee, the men puffing away on their long pipes, while Mynheer Joost read aloud to them a letter. It was from a distant relative of the Joost family who lived in New York City.

You know, of course, that the Dutch were among the first to settle in America, and in the present great city of New York. In those early days a great-great-grand-uncle of Mynheer Joost had gone to the island of Manhattan, and made his home, and now one of his descendants, a Mr. Sturteveldt, who was a merchant in New York City, was anxious to learn something about his family in Holland. He had heard of Mynheer Joost through a friend of his who was fond of flowers, and who had once come to Holland to buy some of Mynheer Joost's beautiful tulips.

So Mr. Sturteveldt had written Mynheer Joost many letters and Mynheer Joost had written him many letters. Finally Mr. Sturteveldt wrote and said he very much wished his only son Theodore to see Holland, and to become acquainted with his Dutch relatives. Upon this, Mynheer Joost had invited Theodore to come and spend some time with them, and this letter that he was now reading said that Theodore was to sail ill a few days in one of the big steamers that sail between New York and Rotterdam, under the care of the captain, and requested that Mynheer Joost would make arrangements to have him met at Rotterdam.

No wonder they all had to talk it over between many sips of coffee and puffs from the long pipes. It was a great event for the Joost family. As for Pieter and Wilhelmina, they could talk and think of nothing else, and Wilhelmina went about all the time murmuring to herself, "How do you do?" and "I am very pleased to see you," and "I hope you had a pleasant voyage," so as to be sure to say it correctly when her American cousin should arrive.

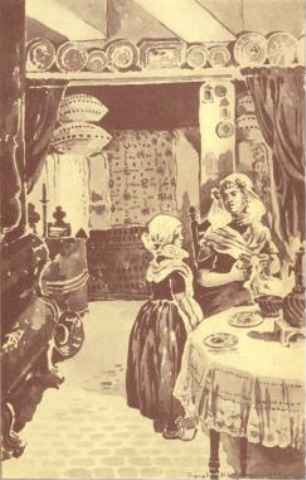

"HOW OLD IS COUSIN THEODORE, MOTHER?" ASKED

WILHELMINA"

"How old is Cousin Theodore, mother?" asked Wilhelmina, as she was helping to give the "show-room" its weekly cleaning. "Just twelve, I believe," said her mother.

"And coming all by himself! I should be frightened nearly to death," said Wilhelmina, who was polishing the arm of a chair so hard that the little gold ornaments on her cap bobbed up and down.

Wilhelmina was short and chubby, and her short blue dress, gathered in as full around her waist as could be, made her look chubbier still. Over her tight, short-sleeved bodice was crossed a gaily flowered silk handkerchief, and around her head, like a coronet, was a gold band from which hung on either side a gold ornament, which looked something like a small corkscrew curl of gold. On top of all this she wore a pretty little lace cap; and what was really funny, her earrings were hung in her cap instead of in her ears! To-day she had on a big cotton working-apron, instead of the fine silk one which she usually wore.

Wilhelmina and her mother were dressed just alike, only Mevrouw's dress was even more bunchy, for she had on about five heavy woollen skirts. This is a Dutch fashion, and one wonders how the women are able to move around so lively.

"Oh, mother, you are putting away another roll of linen!" and Wilhelmina even forgot the coming of her new cousin for the moment, so interested was she as she saw the mother open the great linen-press. This linen-press was the pride of Mevrouw Joost's heart, for piled high on its shelves were rolls and rolls of linen, much of it made from the flax which grew upon their place. Mevrouw Joost herself had spun the thread on her spinning-wheel which stood in one corner of the room, and then it had been woven into cloth.

Some of these rolls of linen were more than a hundred years old, for they had been handed down like the china and silver. The linen of a Dutch household is reckoned a very valuable belonging indeed, and Wilhelmina watched her mother smooth the big rolls which were all neatly tied up with coloured ribbons, with a feeling of awe, for she knew that they were a part of their wealth, and that some day, when she had a house of her own, some of this old family linen would be given her, and then she, too, would have a big linen-press of which to be proud.

Just as Mevrouw Joost closed up the big "show-room" there came a cry from the road of "Eggs, eggs, who'll give us eggs?"

"There come the children begging for Easter eggs," said Wilhelmina as she ran to the door.

At the gate were three little children waving long poles on which were fastened evergreen and flowers, and singing a queer Dutch song about Easter eggs.

"May I give them some, mother?"

"Yes, one each, though I think their pockets are stuffed out with eggs, now," answered Mevrouw.

But if they already did have their pockets stuffed, the children were delighted to get the three that Wilhelmina brought out to them, and went on up the road, still singing, to see how many they could get at the next house.

The Dutch children amuse themselves for some days before Easter by begging for eggs in this way, which they take to their own homes and dye different colours and then exhibit to their friends. On Easter Day there is more fun, for they all gather in the meadows and roll the eggs on the grass, each trying to hit and break those of his neighbours.

At last the day came when Pieter and Wilhelmina were to see their new cousin for the first time. Their father had gone to Rotterdam to meet the steamship and bring Theodore back with him.

The twins hurried from school, and hurried through dinner, and in fact hurried with everything they did. Then they put on their holiday clothes and kept running up the road to see if their father and Theodore were coming, although they knew that it would be hours before they would reach home. But of course, just when they were not looking for them, in walked the father and said: "Here is your Cousin Theodore, children; make him welcome.'' And there stood a tall lad, much taller than Pieter, though they were the same age, holding out his hand and talking English so fast that it made their heads swim.

Pieter managed to say "How do you do? I am glad you have come," but poor Wilhelmina m every word of her English flew out of her head, and all she could think to say was, "Ik dank v, mijnheer,"--"Thank you, sir."

Then suddenly the children all grew as shy as could be, but after they had eaten of Mevrouw's good supper, they grew sociable and Theodore told them all about his voyage over, and Pieter found that he could understand him better than at first. Even Wilhelmina got in a few English words, and when Pieter and Theodore went to sleep together, in what Theodore called a "big box," anybody would have thought they had known each other all their lives.

The three young cousins were soon the best of friends; and as for Theodore, everything was so new and strange to him that he said it was like a big surprise party all the time. He said, too, that he was going to be a real Dutchman while he was with them, and nothing would do but that he must have a suit of clothes just like Pieter's, and a tall cap. How they all laughed the first time he tried to walk in the big wooden shoes! But it wasn't long before he could run in them as fast as the twins.

Click here to continue to the next section of B. McManus' Our Little Dutch Cousin.