|

CHAPTER

IV

THE

PALACE OF NIGHT

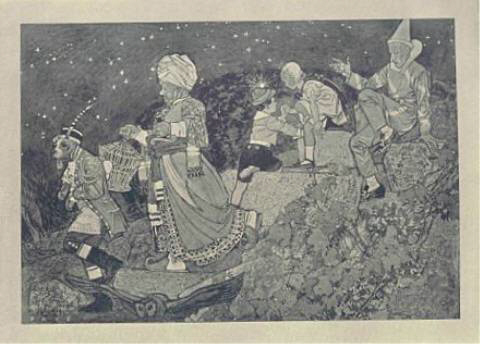

SOME time after, the Children and their friends met at the first dawn

to go to

the Palace of Night, where they hoped to find the Blue Bird. Several of

the

party failed to answer to their names when the roll was called. Milk,

for whom

any sort of excitement was bad, was keeping her room. Water sent an

excuse: she

was accustomed always to travel in a bed of moss, was already half-dead

with

fatigue and was afraid of falling ill. As for Light, she had been on

bad terms

with Night since the world began; and Fire, as a relation, shared her

dislike.

Light kissed the Children and told Tylô the way, for it was

his business to

lead the expedition; and the little band set out upon its road.

You can imagine dear

Tylô trotting ahead, on his hind-legs, like a

little man, with his nose in the air, his tongue dangling down his

chin, his

front paws folded across his chest. He fidgets, sniffs about, runs up

and down,

covering twice the ground without minding how tired it makes him. He is

so full

of his own importance that he disdains the temptations on his path: he

neglects

the rubbish-heaps, pays no attention to anything he sees and cuts all

his old

friends.

Poor Tylô! He was

so delighted to become a man; and yet he was no

happier than before! Of course, life was the same to him, because his

nature had

remained unchanged. What was the use of his being a man, if he

continued to feel

and think like a dog? In fact, his troubles were increased a

hundred-fold by the

sense of responsibility that now weighed upon him.

"Ah!" he said, with a sigh,

for he was joining blindly in his

little gods' search, without for a moment reflecting that the end of

the journey

would mean the end of his life. "Ah," he said, "if I got hold of

that rascal of a Blue Bird, trust me, I wouldn't touch him even with

the tip of

my tongue, not if he were as plump and sweet as a quail!"

Bread followed solemnly,

carrying the cage; the two Children came next;

and Sugar brought up the rear.

But where was the Cat? To

discover the reason of her absence, we must go

a little way back and read her thoughts. At the time when Tylette

called a

meeting of the Animals and Things in the Fairy's hall, she was

contemplating a

great plot which would aim at prolonging the journey; but she had

reckoned

without the stupidity of her hearers:

The

road to the Palace of Night was rather long and rather dangerous

The

road to the Palace of Night was rather long and rather dangerous

"The idiots," she thought,

"have very nearly spoilt the

whole thing by foolishly throwing themselves at the Fairy's feet, as

though they

were guilty of a crime. It is better to rely upon one's self alone. In

my

cat-life, all our training is founded on suspicion; I can see that it

is just

the same in the life of men. Those who confide in others are only

betrayed; it

is better to keep silent and to be treacherous one's self."

As you see, my dear little

readers, the Cat was in the same position as

the Dog: she had not changed her soul and was simply continuing her

former

existence; but, of course, she was very wicked, whereas our dear

Tylô was, if

anything, too good. Tylette, therefore, resolved to act on her own

account and

went, before daybreak, to call on Night, who was an old friend of hers.

The road to the Palace of

Night was rather long and rather dangerous. It

had precipices on either side of it; you had to climb up and climb down

and then

climb up again among high rocks that always seemed waiting to crush the

passers-by. At last, you came to the edge of a dark circus; and there

you had to

go down thousands of steps to reach the black-marble underground palace

in which

Night lived.

The Cat, who had often been

there before, raced along the road, light as

a feather. Her cloak, borne on the wind, streamed like a banner behind

her; the

plume in her hat fluttered gracefully; and her little grey kid boots

hardly

touched the ground. She soon reached her destination and, in a few

bounds, came

to the great hall where Night was.

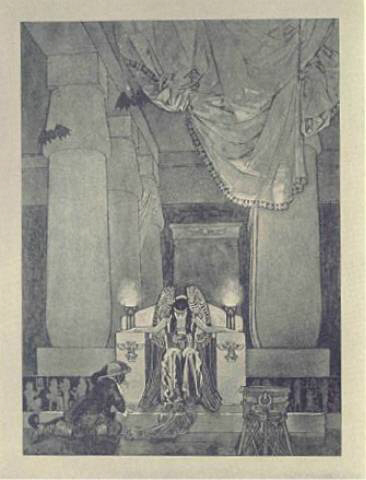

It was really a wonderful

sight. Night, stately and grand as a Queen,

reclined upon her throne; she slept; and not a glimmer, not a star

twinkled

around her. But we know that the night has no secrets for cats and that

their

eyes have the power of piercing the darkness. So Tylette saw Night as

though it

were broad daylight.

Before waking her, she cast a

loving glance at that motherly and familiar

face. It was white and silvery as the moon; and its unbending features

inspired

both fear and admiration. Night's figure, which was half visible

through her

long black veils, was as beautiful as that of a Greek statue. She had

no arms;

but a pair of enormous wings, now furled in sleep, came from her

shoulders to

her feet and gave her a look of majesty beyond compare. Still, in spite

of her

affection for her best of friends, Tylette did not waste too much time

in gazing

at her: it was a critical moment; and time was short. Tired and jaded

and

overcome with anguish, she sank upon the steps of the throne and mewed,

plaintively:

"It is I, Mother Night!... I

am worn out!"

Night is of an anxious nature

and easily alarmed. Her beauty, built up of

peace and repose, possesses the secret of Silence, which life is

constantly

disturbing: a star shooting through the sky, a leaf falling to the

ground, the

hoot of an owl, a mere nothing is enough to tear the black velvet pall

which she

spreads over the earth each evening. The Cat, therefore, had not

finished

speaking, when Night sat up, all quivering. Her immense wings beat

around her;

and she questioned Tylette in a trembling voice. As soon as she had

learnt the

danger that threatened her, she began to lament her fate. What! A man's

son

coming to her palace! And, perhaps, with the help of the magic diamond,

discovering her secrets! What should she do? What would become of her?

How could

she defend herself? And, forgetting that she was sinning against

Silence, her

own particular god, Night began to utter piercing screams. It was true

that

falling into such a commotion was hardly likely to help her find a cure

for her

troubles. Luckily for her, Tylette, who was accustomed to the

annoyances and

worries of human life, was better armed. She had worked out her plan

when going

ahead of the children; and she was hoping to persuade Night to adopt

it. She

explained this plan to her in a few words:

"I see only one thing for it,

Mother Night: as they are children, we

must give them such a fright that they will not dare to insist on

opening the

great door at the back of the hall, behind which the Birds of the Moon

live and

generally the Blue Bird too. The secrets of the other caverns will be

sure to

scare them. The hope of our safety lies in the terror which you will

make them

feel."

There was clearly no other

course to take. But Night had not time to

reply, for she heard a sound. Then her beautiful features contracted;

her wings

spread out angrily; and everything in her attitude told Tylette that

Night

approved of her plan.

"Here they are!" cried the

Cat.

The little band came marching

down the steps of Night's gloomy staircase.

Tylô pranced bravely in front, whereas Tyltyl looked around

him with an anxious

glance. He certainly found nothing to comfort him. It was all very

magnificent,

but very terrifying. Picture a huge and wonderful black marble hall, of

a stern

and tomb-like splendour. There is no ceiling visible; and the ebony

pillars that

surround the amphitheatre shoot up to the sky. It is only when you lift

your

eyes up there that you catch the faint light falling from the stars.

Everywhere,

the thickest darkness reigns. Two restless flames –

no more – flicker

on

either side of Night's throne, before a monumental door of brass.

Bronze doors

show through the pillars to the right and left.

The Cat rushed up to the

Children:

"This way, little master,

this way!... I have told Night; and she is

delighted to see you."

Tylette's soft voice and

smile made Tyltyl feel himself again; and he

walked up to the throne with a bold and confident step, saying:

"Good-day, Mrs. Night!"

Night was offended by the

word, "Good-day," which reminded her

of her eternal enemy Light, and answered drily:

"Good-day?.... I am not used

to that!... You might say, Good-night,

or, at least, Good-evening!"

Our hero was not prepared to

quarrel. He felt very small in the presence

of that stately lady. He quickly begged her pardon, as nicely as he

could; and

very gently asked her leave to look for the Blue Bird in her palace.

"I have never seen him, he is

not here!" exclaimed Night,

flapping her great wings to frighten the boy.

But, when he insisted and

gave no sign of fear, she herself began to

dread the diamond, which, by lighting up her darkness, would completely

destroy

her power; and she thought it better to pretend to yield to an impulse

of

generosity and at once to point to the big key that lay on the steps of

the

throne.

Without a moment's

hesitation, Tyltyl seized hold of it and ran to the

first door of the hall.

Everybody shook with fright.

Bread's teeth chattered in his head; Sugar,

who was standing some way off, moaned with mortal anguish; Mytyl

howled:

"Where

is Sugar?... I want to go home!" Meanwhile,

Tyltyl, pale and resolute, was trying to open the door, while Night's

grave

voice, rising above the din, proclaimed the first danger. "It's the

Ghosts!"

"Oh, dear!" thought Tyltyl.

"I have never seen a ghost: it

must be awful!"

The faithful Tylô,

by his side, was panting with all his might, for dogs

hate anything uncanny.

At last, the key grated in

the lock. Silence reigned as dense and heavy

as the darkness. No one dared draw a breath. Then the door opened; and,

in a

moment, the gloom was filled with white figures running in every

direction. Some

lengthened out right up to the sky; others twined themselves round the

pillars;

others wriggled ever so fast along the ground. They were something like

men, but

it was impossible to distinguish their features; the eye could not

catch them.

The moment you looked at them, they turned into a white mist. Tyltyl

did his

best to chase them; for Mrs. Night kept to the plan contrived by the

Cat and

pretended to be frightened. She had been the Ghosts' friend for

hundreds and

hundreds of years and had only to say a word to drive them in again;

but she was

careful to do nothing of the sort and, flapping her wings like mad, she

called

upon all her gods and screamed:

"Drive them away! Drive them

away! Help! Help!" But the poor

Ghosts, who hardly ever come out now that Man no longer believes in

them, were

much too happy at taking a breath of air; and, had it not been that

they were

afraid of Tylô, who tried to bite their legs, they would

never have been got

indoors.

"Oof!" gasped the Dog, when

the door was shut at last. "I

have strong teeth, goodness knows; but chaps like those I never saw

before! When

you bite them, you'd think their legs were made of cotton!"

By this time, Tyltyl was

making for the second door and asking:

"What's behind this one?'

Night made a gesture as

though to put him off. Did the obstinate little

fellow really want to see everything?

"Must I be careful when I

open it?" asked Tyltyl.

"No," said Night, "it is not

worth while. It's the

Sicknesses. They are very quiet, the poor little things! Man, for some

time, has

been waging such war upon them! . . Open and see for yourself .... "

Tyltyl threw the door wide

open and stood speechless with astonishment:

there was nothing to be seen...

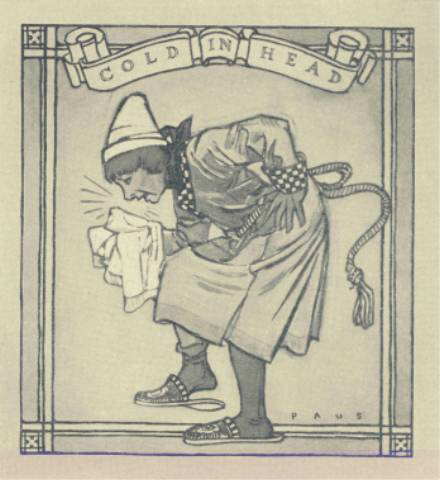

He was just about to close

the door again, when he was hustled aside by a

little body in a dressing-gown and a cotton night-cap, who began to

frisk about

the hall, wagging her head and stopping every minute to cough, sneeze

and blow

her nose ... and to pull on her slippers, which were too big for her

and kept

dropping off her feet. Sugar, Bread and Tyltyl were no longer

frightened and

began to laugh like anything. But they had no sooner come near the

little person

in the cotton night-cap than they themselves began to cough and sneeze.

"It's the least important of

the Sicknesses," said Night.

"It's Cold-in-the-Head."

"Oh, dear, oh, dear!" thought

Sugar. "If my nose keeps on

running like this, I'm done for! I shall melt!"

Night

sat up, all quivering. Her immense wings beat around her; and she

questioned

Tylette in a trembling voice

Night

sat up, all quivering. Her immense wings beat around her; and she

questioned

Tylette in a trembling voice

Poor

Sugar! He did not know

where to hide himself. He had become very

much attached to life since the journey began, for he had fallen over

head and

ears in love with Water! And yet this love caused him the greatest

worry.

Miss Water was a tremendous

flirt, expected a lot of attention and was

not particular whom she mixed with; but mixing too much with Water was

an

expensive luxury, as poor Sugar found to his cost; for, at every kiss

he gave

her, he left a bit of himself behind, until he began to tremble for his

life.

When he suddenly found

himself attacked by Cold-in-the-Head, he would

have had to fly from the palace, but for the timely aid of our dear

Tylô, who

ran after the little minx and drove her back to her cavern, amidst the

laughter

of Tyltyl and Mytyl, who thought gleefully that, so far, the trial had

not been

very terrible.

The boy, therefore, ran to

the next door with still greater courage.

"Take care!" cried Night, in

a dreadful voice. "It's the

Wars! They are more powerful than ever! I daren't think what would

happen, if

one of them broke loose! Stand ready, all of you, to push back the

door!"

Night had not finished

uttering her warnings, when the plucky little

fellow repented his rashness. He tried in vain to shut the door which

he had

opened: an invincible force was pushing it from the other side, streams

of blood

flowed through the cracks; flames shot forth; shouts, oaths and groans

mingled

with the roar of cannon and the rattle of musketry. Everybody in the

Palace of

Night was running about in wild confusion. Bread and Sugar tried to

take to

flight, but could not find the way out; and they now came back to

Tyltyl and put

their shoulders to the door with despairing force.

The Cat pretended to be

anxious, while secretly rejoicing:

"This may be the end of it,"

she said, curling her whiskers.

"They won't dare to go on after this."

Dear Tylô made

superhuman efforts to help his little master, while Mytyl

stood crying in a corner.

At last, our hero gave a

shout of triumph:

"Hurrah! They're giving way!

Victory! Victory! The door is

shut!"

At the same time, he dropped

on the steps, utterly exhausted, dabbing his

forehead with his poor little hands which shook with terror.

"Well?" asked Night, harshly.

"Have you had enough? Did

you see them?"

"Yes, yes!" replied the

little fellow, sobbing. "They are

hideous and awful… I don't think they have the Blue

Bird…"

"You may be sure they

haven't," answered Night, angrily.

"If they had, they would eat him at once. . . You see there is nothing

to

be done..."

Tyltyl drew himself up

proudly:

"I must see everything," he

declared. "Light said

so...."

"It's an easy thing to say,"

retorted Night, "when one's

afraid and stays at home!"

"Let us go to the next door,"

said Tyltyl, resolutely.

"What's in here?"

"This is where I keep the

Shades and the Terrors!"

Tyltyl reflected for a minute:

"As far as Shades go," he

thought, "Mrs. Night is poking

fun at me. It's more than an hour since I've seen anything but shade in

this

house of hers; and I shall be very glad to see daylight again. As for

the

Terrors, if they are anything like the Ghosts, we shall have another

good

joke."

Our friend went to the door

and opened it, before his companions had time

to protest. For that matter, they were all sitting on the floor,

exhausted with

the last fright; and they looked at one another in astonishment, glad

to find

themselves alive after such a scare. Meanwhile, Tyltyl threw back the

door and

nothing came out:

"There's no one there!" he

said.

"Yes, there is! Yes, there

is! Look out!" said Night, who was

still shamming fright.

She was simply furious. She

had hoped to make a great impression with her

Terrors; and, lo and behold, the wretches, who had so long been snubbed

by Man,

were afraid of him! She encouraged them with kind words and succeeded

in coaxing

out a few tall figures covered with grey veils. They began to run all

around the

hall until, hearing the Children laugh, they were seized with fear and

rushed

indoors again. The attempt had failed, as far as Night was concerned,

and the

dread hour was about to strike. Already, Tyltyl was moving towards the

big door

at the end of the hall. A few last words took place between them:

"Do not open that one!" said

Night, in awe-struck tones.

"Why not?"

"Because it's not allowed!"

"Then it's here that the Blue

Bird is hidden!"

"Go no farther, do not tempt

fate, do not open that door!"

"But why?" again asked

Tyltyl, obstinately.

Thereupon, Night, irritated

by his persistency, flew into a rage, hurled

the most terrible threats at him, and ended by saying:

"Not one of those who have

opened it, were it but by a hair's

breadth, has ever returned alive to the light of day! It means certain

death;

and all the horrors, all the terrors, all the fears of which men speak

on earth

are as nothing compared with those which await you if you insist on

touching

that door!"

"Don't do it, master dear!"

said Bread, with chattering teeth.

"Don't do it! Take pity on us! I implore you on my knees!"

"You are sacrificing the

lives of all of us," mewed the Cat.

"I won't! I sha'n't!" sobbed

Mytyl.

"Pity! Pity!" whined Sugar,

wringing his fingers.

All of them were weeping and

crying, all of them crowded round Tyltyl.

Dear Tylô alone, who respected his little master's wishes,

dared not speak a

word, though he fully believed that his last hour had come. Two big

tears rolled

down his cheeks; and he licked Tyltyl's hands in despair. It was really

a most

touching scene; and for a moment, our hero hesitated. His heart beat

wildly, his

throat was parched with anguish, he tried to speak and could not get

out a

sound: besides, he did not wish to show weakness in the presence of his

hapless

companions!

"If I have not the strength

to fulfil my task," he said to

himself, "who will fulfil it? If my friends behold my distress, it is

all

up with me: they will not let me go through with my mission and I shall

never

find the Blue Bird!"

At this thought, the boy's

heart leapt within his breast and all his

generous nature rose in rebellion. It would never do to be, perhaps,

within

arm's length of happiness and not to try for it, at the risk of dying

in the

attempt, to try for it and hand it over at last to all mankind!

That settled it! Tyltyl

resolved to sacrifice himself. Like a true hero,

he brandished the heavy golden key and cried:

"I must open the door!"

He ran up to the great door,

with Tylô panting by his side. The poor Dog

was half-dead with fright, but his pride and his devotion to Tyltyl

obliged him

to smother his fears:

"I shall stay," he said to

his master, "I'm not afraid! I

shall stay with my little god!"

In the meantime, all the

others had fled. Bread was crumbling to bits

behind a pillar; Sugar was melting in a corner with Mytyl in his arms;

Night and

the Cat, both shaking with fury, kept to the far end of the hall.

Then Tyltyl gave

Tylô a last kiss, pressed him to his heart and, with

never a tremble, put the key in the lock. Yells of terror came from all

the

corners of the hall, where the runaways had taken shelter, while the

two leaves

of the great door opened by magic in front of our little friend, who

was struck

dumb with admiration and delight. What an exquisite surprise! A

wonderful garden

lay before him, a dream-garden filled with flowers that shone like

stars,

waterfalls that came rushing from the sky and trees which the moon had

clothed

in silver. And then there was something whirling like a blue cloud

among the

clusters of roses. Tyltyl rubbed his eyes, could not believe his

senses. He

waited, looked again and then dashed into the garden, shouting like

mad:

"Come quickly!... Come

quickly!... They are here! . . We have them

at last!... Millions of blue birds! . . Thousands of millions! . .

Come,

Mytyl!... Come, Tylô!... Come, all! ... Help me!... You can

catch them by

handfuls! . ."

Reassured at last, his

friends came running up and all darted in among

the birds, seeing who could catch the most:

"I've caught seven already!"

cried Mytyl. "I can't hold

them!"

"Nor can I!" said Tyltyl. "I

have too many of them! ...

They're escaping from my arms! ... Tylô has some too!... Let

us go out, let us

go!... Light is waiting for us!... How pleased she will be!... This

way, this

way ...."

And they all danced and

scampered away in their glee, singing songs of

triumph as they went.

Night and the Cat, who had

not shared in the general rejoicing, crept

back anxiously to the great door; and Night whimpered:

"Haven't they got him...."

"No," said the Cat, who saw

the real Blue Bird perched high up

on a moon-beam... "They could not reach him, he kept too high. . ."

Our friends in all haste ran

up the numberless stairs between them and

the daylight. Each of them hugged the birds which he had captured,

never

dreaming that every step which brought them nearer to the light was

fatal to the

poor things, so that, by the time they came to the top of the

staircase, they

were carrying nothing but dead birds. Light was waiting for them

anxiously:

"Well, have you caught him?" she asked.

"Yes, yes?" said Tyltyl.

"Lots of them! There are

thousands! Look!"

As he spoke, he held out the

dear birds to her and saw, to his dismay,

that they were nothing more than lifeless corpses' their poor little

wings were

broken and their heads drooped sadly from their necks! The boy, in his

despair,

turned to his companions. Alas, they too were hugging nothing but dead

birds!

Wagging

her head and stopping every minute to cough, sneeze and blow her nose

Wagging

her head and stopping every minute to cough, sneeze and blow her nose

Then Tyltyl threw himself

sobbing into Light's arms. Once more, all his

hopes were dashed to the ground.

"Do not cry, my child," said

Light. "You did not catch the

one that is able to live in broad daylight ....we shall find him

yet..."

"Of course, we shall find

him," said Bread and Sugar, with one

voice.

They were great boobies, both

of them; but they wanted to console the

boy. As for friend Tylô, he was so much put out that he

forgot his dignity for

a moment and, looking at the dead birds, exclaimed:

"Are they good to eat, I

wonder?"

The party set out to walk

back and sleep in the Temple of Light. It was a

melancholy journey; all regretted the peace of home and felt inclined

to blame

Tyltyl for his want of caution. Sugar edged up to Bread and whispered

in his

ear:

"Don't you think, Mr.

Chairman, that all this excitement is very

useless?"

And Bread, who felt flattered

at receiving so much attention, answered,

pompously:

"Never you fear, my dear

fellow, I shall put all this right. Life

would be unbearable if we had to listen to all the whimsies of that

little

madcap! . . To-morrow, we shall stay in bed!..."

They forgot that, but for the

boy at whom they were sneering, they would

never have been alive at all; and that, if he had suddenly told Bread

that he

must go back to his pan to be eaten and Sugar that he was to be cut

into small

lumps to sweeten Daddy Tyl's coffee and Mummy Tyl's syrups, they would

have

thrown themselves at their benefactor's feet and begged for mercy. In

fact, they

were incapable of appreciating their good luck until they were brought

face to

face with bad.

Poor things! The Fairy

Bérylune, when making them a present of their

human life, ought to have thrown in a little wisdom. They were not so

much to

blame. Of course, they were only following Man's example. Given the

power of

speaking, they jabbered; knowing how to judge, they condemned; able to

feel,

they complained. They had hearts which increased their sense of fear,

without

adding to their happiness. As to their brains, which could easily have

arranged

all the rest, they made so little of them that they had already grown

quite

rusty; and, if you could have opened their heads and looked at the

works of

their life inside, you would have seen the poor brains, which were

their most

precious possession, jumping about at every movement they made and

rattling in

their empty skulls like dry peas in a pod.

Fortunately, Light, thanks to

her wonderful insight, knew all about their

state of mind. She determined, therefore, to employ the Elements and

Things no

more than she was obliged to:

"They are useful," she

thought, "to feed the children and

amuse them on the way; but they must have no further share in the

trials,

because they have neither courage nor conviction."

Meanwhile, the party walked

on, the road widened out and became

resplendent; and, at the end, the Temple of Light stood on a crystal

height,

shedding its beams around. The tired Children made the Dog carry them

pick-a-back by turns; and they were almost asleep when they reached the

shining

steps.

|