| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

XXVII In which, much against my will, I eat three cherry pies; see myself for the first time on a moving-picture screen and discover that I am a hopeless failure on the films. "REGISTER surprise! Register surprise!" the director ordered in a low tense voice, while I struggled to get up without damaging the pie. I turned my head toward the clicking camera, and suddenly it seemed like a great eye watching me. I gazed into the round black lens, and it seemed to swell until it was yards across. I tried to pull my face into an expression of surprise, but the muscles were stiff and I could only stare fascinated at the lens. The clicking stopped. "Too bad. You looked at the camera,. Try it again," said the director, making a note of the number of feet of film spoiled. He was a very patient director; he stopped the camera and placed the pie on top of it for safety, while I fell through the trap-door twice and twice played the scene through, using the pie tin. Then the pie was placed under my coat again, the camera began to click, and again I started the scene. But the clicking drew my attention to the lens in spite of myself. I managed to keep from looking directly at it, but I felt that my acting was stiff, and half-way through the scene the camera stopped again. "Out of range," said the camera man carelessly, and lighted a cigarette. I had forgotten the circle of dots on the floor and crossed them. I had eaten a large piece of the pie. There was a halt while another was brought, and the director, after an anxious look at the sun, used the interval in playing the scene through himself, falling through the trap-door, registering surprise and apprehension and panic at the proper points, and impressing upon me the way it was done. Then I tried it again. All that afternoon I worked, black and blue from countless falls on the cement floor, perspiring in the intense heat, and eating no less than three large pies. They were cherry pies, and I had never cared much for them at any time. When the light failed that evening the director, with a troubled frown, thoughtfully folded the working script and dismissed the camera man. Most of the actors in the other companies had gone; the wilderness of empty sets looked weird in the shadows. A boy appeared, caught the rats by their tails, and popped them back into their box. "Well, that's all for to-day. We'll try it again to-morrow," the director said, not looking at me. "I guess you'll get the hang of it all right, after a while." In my dressing-room I scrubbed the paint from my face and neck with vicious rubs. I knew I had failed miserably and my self-esteem smarted at the thought. Even if I had succeeded, I said bitterly, what was the fun in a life like that? No excitement, no applause, just hard work all day and long empty evenings with nothing to do. Only two considerations prevented me from canceling my contract and quitting at once — I was getting two hundred dollars a week, and I would not admit to myself that I — I, who had been a success with William Gillette and a star with Carno — was a failure in the films. Nevertheless, I was in a black mood that night, and when after dinner the waiter, bending deferentially at my elbow, insinuated politely, "The cherry pie is very good, sir," he fell back aghast at the language I used. Work at the studio began at eight next morning, and I arrived very tired and ill-tempered because of waking so early. We began immediately on the same scene, and after I had ruined some more film by unexpectedly landing on a rat when I fell through the trapdoor, we managed to get it done, to my relief. However, all that week, and the next, my troubles increased. We played all the scenes which occurred in one set before we went on to the next set, so we were obliged to take the scenes at haphazard through the play, with no continuity or apparent connection. The interiors were all played on the stage, and most of the exteriors were taken "on location," that is, somewhere in the country. It was confusing, after being booted through a door, to be obliged to appear on the other side of it two days later, with the same expression, and complete the tumble begun fifteen miles away. It was still more confusing to play the scenes in reverse order, and I ruined three hundred feet of film by losing my hat at the end of a scene, when the succeeding one had already been played with my hat on. At the end of the second week the comedy was all on the film and the director and I were being polite to each other with great effort. I was angry with every one and everything, my nerves worn thin with the early hours and unaccustomed work, and he was worried because I had made him a week late in producing the film. The day the negative was done Mack Sennett arrived from New York, and I met him with a jauntiness which was a hollow mockery of my real feeling. "Well, they tell me the film's done," he said heartily, shaking my hand. "Now you're going to see yourself as others see you for the first time. Is the dark room ready? Let's go and see how you look on the screen." The director led the way, and the three of us entered a tiny perfectly dark room. I could hear my heart beating while we waited, and talked nervously to cover the sound of it. Then there was a click, the shutter opened, and the picture sprang out on the screen. It was the negative, which is always shown before the real film is made, and on it black and white were reversed. It was several seconds before I realized that the black-faced man in white clothes, walking awkwardly before me, was myself. Then I stared in horror. Funny? A blind man couldn't have laughed at it. I had ironed out entirely any trace of humor in the scenario. It was stiff, wooden, stupid. We sat there in silence, seeing the picture go on, seeing it become more awkward, more constrained, more absurd with every flicker. I felt as though the whole thing were a horrible nightmare of shame and embarrassment. The only bearable thing in the world was the darkness; I felt I could never come out into the light again, knowing I was the same man as the inane ridiculous creature on the film. Half-way through the picture Mr. Sennett took pity on me and stopped the operator. "Well, Chaplin, you didn't seem to get it that time," he said. "What's wrong, do you suppose?" "I don't know," I said. "Yes, it's plain we can't release this," the director put in moodily. "Two thousand feet of film spoiled." "Oh, damn your film!" I burst out in a fury, and rising with a spring which upset my chair I slammed open the door and stalked out. "Well, here is where I quit the pictures," I thought. Mr. Sennett and the director overtook me before I reached my dressing-room and we talked it over. I felt that I would never make a moving-picture actor, but Mr. Sennett was more hopeful. "You're a crackerjack comedian," he said. "And you'll photograph well. All you need is to get camera-wise. We'll try you out in something else; I'll direct you, and you will get the hang of the work all right." The director brought out a mass of scenarios which had been passed up to him by the scenario department and Mr. Sennett picked out one and ordered the working script of it made immediately. Next day we set to work together on it; Mr. Sennett patient, good-humored, considerate, coaching me over and over in every gesture and expression; I with a hard tense determination to make a success this time. We worked another week on this second play, using every hour of good daylight. It was not entirely finished then, but enough was done to give an idea of its success, and again the negative was sent to the dark room for review.

I went to see it

with the

sensations of dread and shrinking one feels at sight of a dentist's

chair, and my worst fears were justified. The film was worse than the

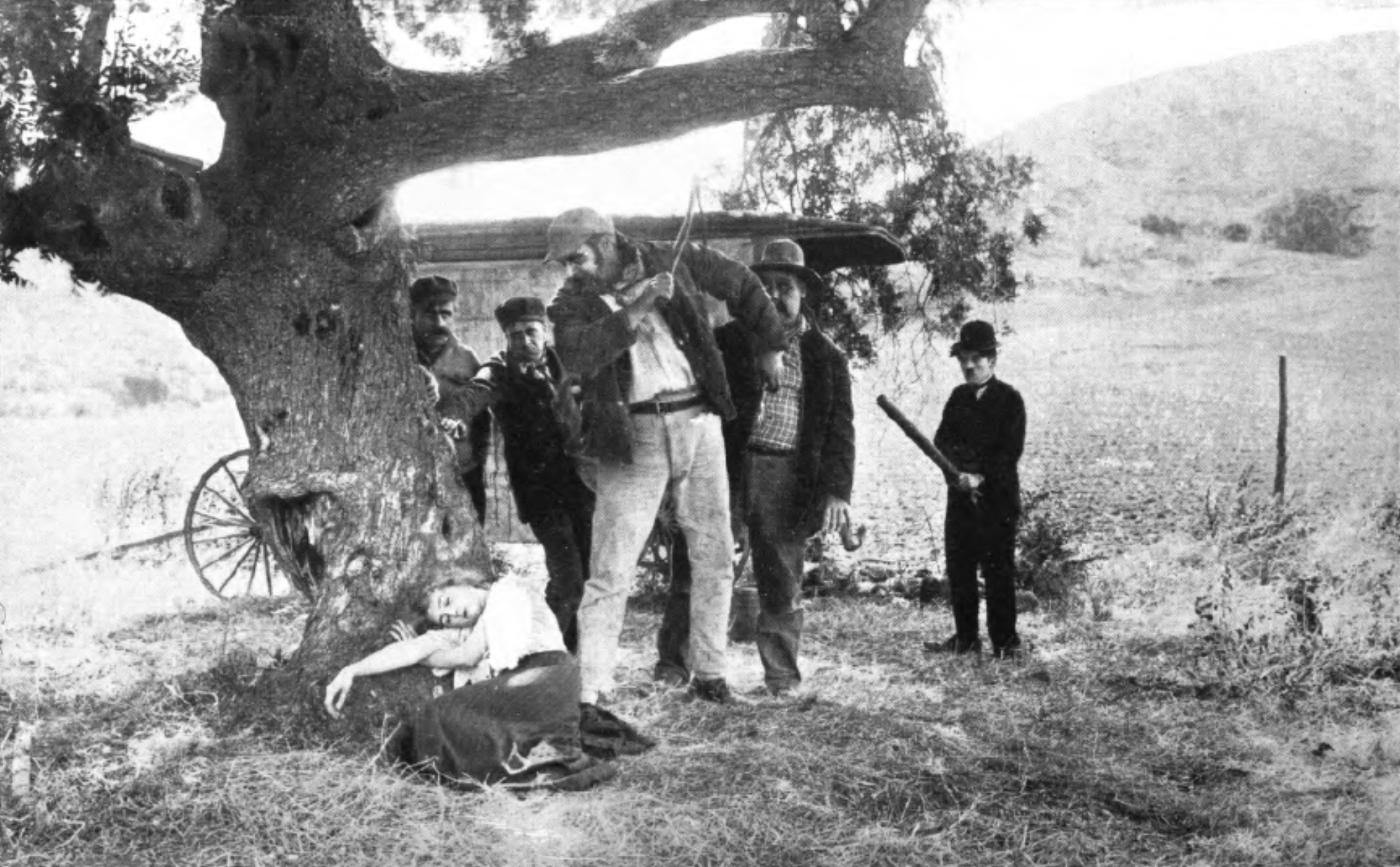

first one — utterly stupid and humorless.  A Scene from a Chaplin Movie |