| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| "You

have such a February face, So full of frost, of storm, and cloudiness!" Shakespeare.

IT is perhaps impossible for an intelligent person to prosecute any line of research, without finding himself instinctively grouping his newly acquired facts according to some system, it may be merely fanciful and erroneous, or it may be more or less scientific and accurate. The human mind has an innate propensity to systematic arrangement, which doubtless has its ground in this, that any fact, pure and simple, is of very little interest, except as considered in its relation to other facts. It is as true of every fact as of a human being, that none liveth unto itself. And even without any distinct sense of this truth which prevails throughout the universe, the mind, by its very constitution fitted to the state of the case, governs itself according to this principle. Without such relationship, science, as we understand it, would be impossible, or at best only a heterogeneous accumulation of isolated facts, as devoid of all utility after possession as they would be uninteresting and laborious in the acquisition. Even when the correct fundamental relation subsisting between the facts of a certain class is felt to be as yet undiscovered, as in botany and ornithology, one realizes the need of some provisional system, however erroneous it may be, until the true one shall have been found. As an aid to memory a system is of inestimable value, and in this respect a thoroughly false method may not be so very inferior to the correct one. Birds may be grouped in three ways. That which claims to be the most thoroughly scientific classification is based upon anatomical structure, wherein the size and form of the bill, the number of feathers in the wing, the length and peculiarities of the leg (or tarsus), the number and position of the toes, etc., are among the important criteria for determining the status of the individual. We can all certainly agree in saying, with Lincoln, that "for those that like that kind of a thing, that would be just the kind of a thing they would like;" but if pressed for further unanimity, some of us would have to part company. But for the purposes of field ornithology the distinctions here referred to are almost valueless, as they are too minute to be recognizable at the ordinary distance of observation. Again, they can be grouped according to their habits: either as regards their habitat, as land, shore, and water birds, or as aerial and terrestrial; or with a view to their differences of diet, as carnivorous, insectivorous, and granivorous. But, while all these differences enter into the computation of a bird's status, they are too indefinite in themselves to afford any satisfactory basis of arrangement. The third method, while in a sense more superficial and arbitrary than either of the others, is, after all, the most feasible for merely cursory study, the most natural for outdoor investigation, and the method which any one without suggestion would inevitably adopt after a year's continuous experience, viz., grouping them according to the season of the year when they appear. However shallow this system evidently is, it is none the less efficient for practical purposes. This does not preclude the more detailed grouping according to their evident resemblances of form, color, habitat, habits, and temperament, by which they are found to be differentiated; and while dependent for its validity upon the particular geographical location of the observer, this third method is conditioned by some very interesting facts of science, viz., the laws governing their appearance and disappearance, as they come and go periodically. As the object of these pages is not merely to give a succinct account of the several species one is likely to find in the course of a year's observation, but to make the whole scheme of bird-life more intelligible by treating briefly of the more important phenomena observable among them collectively, it is essential to speak of that curious and extremely interesting phase of their history — bird-migration; and no time is more opportune for this explanation than February — "so full of frost, of storm, and cloudiness," so unfavorable for outdoor study, and immediately preceding the first of the year's migrations. Even the most unobservant person is probably aware that the robins and bluebirds arrive in the spring, and go away some time in the fall; but he is not so likely to know that, on the other hand, there are many species, unknown to him by name or appearance, like kinglets, nuthatches, crossbills, shrikes, pine finches, etc., which reverse this order, and only come at the approach of cold weather or in mid-winter, and disappear in the spring. He may be equally unfamiliar with the fact that still other species, like some of the thrushes, finches, warblers, and greenlets, can be seen only for a few weeks at a time at two different periods in the year, and is perhaps unaware that a very few species are to be found in the woods throughout the whole year. These various movements are not due to the special peculiarities of the several classes, but to the law controlling them all equally, and the apparent complexity of the law resolves into the utmost simplicity when it is understood. Bird-migrations are all in the direction of north and south, and the underlying cause of this is that they are determined chiefly by the two considerations of temperature and food-supply. With uniform climate and abundant subsistence, birds would doubtless remain in their several localities, or approximately so, the entire year. In that case, such of the warblers as find their summer home in northern New England and Canada would also remain there throughout the winter, and we should not be likely to see them except at the personal inconvenience of going where they are. According to nature's laws they pay us a flying visit once or twice a year, and never expect the call to be returned. We must look for some urgently impelling motive for these regular, invariable, and immense journeys undertaken so often by these creatures. We can hardly suppose that a bird that spends the summer in Labrador or Alaska goes down to Central America in the fall and back again in the spring just for the pure fun of it. Shakespeare's allusion to a bird that is with us in the midst of the year as is

a poetic license. At that season every bird is in its home, and not a

guest anywhere. For the true home of a bird must be regarded as the

place where it nests and sings. If a bird be found in the Arctic zone

during the singing and breeding season, that is surely its

heart's home, however far it may travel southward in the later

months to find food, or to avoid the severity of winter's cold. When

we consider what strong local attachments they manifest, causing them

not only to return, hundreds and thousands of miles to the very same

place, but frequently to nest in the same tree year after year, we

may well believe that only some strong necessity can drive them

annually so fax away.

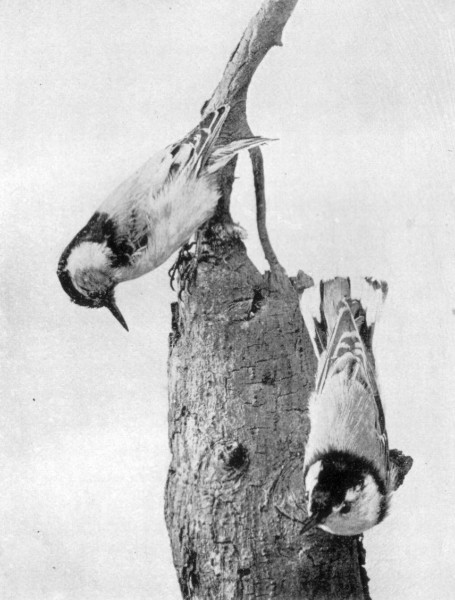

With the exception of the very few that are permanent the year round, such birds as summer in this region move southward in the fall, not only for warmth, but doubtless, in many cases, for the more potent reason that the fruit, grain, insects, etc., on which they have been feeding are no longer obtainable in this latitude. Thus the bobolink is also called "rice-bird," indicating the character of its sustenance while in the south. It may well be doubted whether the robin lacks the physical hardihood to withstand a northern winter, as it is frequently found in New England throughout that season; but in the absence of fruits, grubs, and especially earth-worms, which are its main subsistence, it has a very precarious existence, and ample cause for retirement to the south. On the other hand, the hardier species that from one cause and another summer in the far north, like nuthatches, kinglets, and crossbills, coming southward at the approach of cold weather, find in this latitude both a tolerable climate and adequate subsistence in the eggs and larvæ of insects abundant in the bark of so many trees, and also in the meagre supply of berries and seeds still clinging to the branches and to the dead stalks of last year's growth. And, by the way, we are greatly indebted to these graceful and unobtrusive little scavengers for their constant service in ridding the trees of that which, if allowed to live and develop, would prove so injurious, if not fatal, to our forests. Thus, from one and the same cause, as cold weather approaches, the more northern species come to us, and our own summer birds go south, while in spring the migration is reversed. This accounts for the semi-annual appearance and disappearance of the two groups known as summer residents and winter residents, which being with us for the longest periods comprise all the best-known species. It should be remarked in this connection that the permanence of some species remaining in one locality the year round is doubtless often secured by replacement of some individuals going south by hardier ones from the north, and vice versa. In anatomy and habits the several species of each of these two groups are widely different from each other. Size is no criterion of hardiness, as some of the smallest birds are the most vigorous, while many of the largest are the most delicate. The most conspicuous difference between the two groups is in the generally neutral coloring of winter birds, and the more brilliant plumage of the summer species. Black and white and brown are prevalent in winter; yellow, red, blue, and crimson are frequent in summer. It remains to speak of the third group, which, in the latitude of New York, is perhaps as large as the summer group, comprising all of the least known, but many of the most interesting and beautiful species, resident here neither in summer nor winter, and strictly "transients." They are such as go to greater extremes in their semi-annual migration than any of the foregoing. Summering in northern New England, Canada, Labrador, and even in the Arctic regions, like the fox sparrow and many other finches, some of the thrushes, but especially the warblers, they do not find our climate congenial, nor agreeable food-supplies for the winter months, and their fall migrations carry them farther south, even as far sometimes as Mexico and Central America. As a consequence we are able to see them only in their passage to and fro. And practically our observation of many of them is confined to their spring passage. It is a peculiar fact, for which I can find no explanation, that some species seem to choose a different route for the fall migration from that in the spring — passing to the north through the Atlantic States, and even near the coast in spring, but taking a more inland course on their return. The added fact that the fall migration is made in smaller flocks, and apparently with fewer delays on the route, accounts for their escaping observation even when their course is the same. Strictly speaking, all birds not permanent in one place throughout the year are migrants; but, for convenience in distinguishing this group from the other two, the term is commonly applied only to those that neither summer nor winter with us, and can be seen only in transit. The approach of warm weather — the new impulse of life — starts them in successive flocks northward. Moving by easy stages, so that their advance accords with the later opening of spring in more northerly latitudes, they stop for a brief season here and there, and it is often several weeks before they reach their final destination. Evidently no one species moves in a body, as they seem to come in successive "waves." In making a tour of investigation after an unusually vernal day (and especially after one or two warm and cloudy nights), one is likely to find fresh accessions to such species as had already appeared, as well as forerunners of new species. Thus, while it may be true that none of the individuals remain more than a few days in a place, replenishment will keep a species represented in a given locality for many weeks, which is most fortunate for the student. The fall migrations are less favorable for observations, not only for reasons already given, but for others to be cited hereafter, so that we must rely chiefly upon our opportunities in April and May for learning what we can of the "migrants." Without special attention given to the subject during this period, one will never make the acquaintance of some of the most beautiful and rare specimens, and some of the finest singers as well. The migratory movement of birds begins, for this latitude, sometimes as early as the middle of February, when the song sparrows begin to appear, and the snow-birds considerably increase in number, and continues until a little into June. One of the last migrants to disappear is the olive-backed thrush, which I saw June 2d; and one of the very latest warblers is the "black-poll," which was still here June 4th. But the main host makes its passage between the middle of April and the middle of May. The area occupied summer or winter by any species can never be stated with precision, as it will vary somewhat even from year to year. According to temperature and other conditions, the "wave" may sweep a little farther north or south. A winter species may not appear for several years, and then be reported in great numbers. I think this is the case this winter in New England with the pine grosbeak, which has been rare for many seasons, and now seems to be quite plentiful, one correspondent informing me he has seen hundreds of them. The severity of climate and perhaps scarcity of food have evidently driven them in great numbers from the north. As we approach the boundaries of its range, the individuals of a species are likely to become more and more infrequent, which makes the range more difficult to determine. But the increasing rarity of a species toward its boundaries, and the uncertainty involved in their fluctuating movements, give additional zest in the search for specimens. Thus bird-life has its annual tide, whose "flow" and "ebb" approximately coincide with the months of spring and fall, while the intervening seasons of summer and winter are the periods of quiescence. Inferentially from the foregoing account of migration, the birds for February are much the same as for January. Yet this does not preclude many interesting discoveries in any given area. They are now in a roaming state within their congenial latitude, and not bound by any of the so-called "domestic ties" within very close limitations. They wander hither and thither, either singly or in pairs, or in larger or smaller flocks, having no particular aim in life except to keep as comfortable as possible, and to find something to eat. A specimen found anywhere in January will perhaps remain in that immediate vicinity till spring, or it may wander off more than a hundred miles. Their instincts and circumstances are so unknown to us, that we can feel that we may be on the verge of a discovery at any instant. The demands of nature are paramount, and in the sharpness of hunger one will not be over fastidious as to the company he keeps. One morning, when the newly fallen snow had seriously limited the natural supplies of food, I found an incongruous but apparently happy family feeding most amicably at a spot where provision is regularly made — a gathering composed of peacocks, pigeons, several squirrels, English sparrows, "white-throats," cardinals, and a huge but famishing rat! While the rest of the company did not openly resent the intrusion of this base quadruped, and merely ignored him in the most distant and polite manner, it was evident that he felt an indescribable chill in the atmosphere, for he was plainly ill at ease amid so much beauty and elegance, and he soon made his own motion, and seconded it, to withdraw. The Park is a paradise for the squirrels. One morning in a walk I counted about thirty, chasing through the trees, swaying in sheer sportiveness on slender branches that threatened to break beneath their weight, or sunning themselves by lying prone against the trunks, heads downward, or ensconced under the canopy of their bushy tails enjoying a lunch. They realize their immunity from danger, and often, with the freedom and shamelessness of professional beggars, will follow people about in the hope of getting a dainty morsel from the charitable public. Either in intimacy or desperation I have sometimes had them run up my trousers. Now and then a wild rabbit starts up at your approach and dashes out of sight; and one afternoon the sharp crack of a rifle, that called up visions of blasted hopes and black despair, the victims of which seem to regard the Park as an attractive place wherein with powder and ball to seek the quietus of all their woes, quickly gathered the passers-by to a spot beneath the trees. The tragic episode (for the ball reached its intended mark, and the inanimate form lay stretched on the ground) proved to be the sudden and violent demise of Reynard, encroaching too far within the confines of the metropolis. He would have done better to remain in his wild woodland home; but, like thousands of others, he did not know what was good for him, and was ambitious to go to the city! and his name is added to the long roll of unfortunates of whom city life has been the ruination. A new and beautiful sight this month is a flock of European goldfinches. The attempt is made from time to time to introduce and acclimate in this country some of the noted species of Europe; but unfortunately many, if not most, of such efforts prove fruitless. One day I met in the Park a gentleman whose philanthropy in this direction induces him yearly to have a hundred or more specimens sent over. He had imported a large number of chaffinches, one of the most popular birds in England, and turned them loose in the Park, and was vainly inquiring what had become of them. The starling has also been brought over, and I suspect that on two occasions I have seen it, as it answered the description as far as I could ascertain. This being the songless season, the question was left in doubt. The European goldfinch, which an ornithological writer of England calls "the most beautiful of all our [their] resident birds," is one of the very few thus introduced that are breeding wild in this country, but so rarely found that they are not yet reckoned among our birds in books of ornithology. In some respects they are superior to our American goldfinches, not on the principle that an imported article is the best, but as being rather finer vocalists and with plumage a little richer. It is about five inches long, the fore part of the face is red about the bill, and the rest of the head pure black and white, the breast white, with a tinge of soft brown on each side, and the dark wings conspicuously striped with yellow. They are not yet in song, but their call-note has the same sad quality found in the American species (hence the specific name of the latter, Irish's). The red mask, the abrupt black and white of the head, and the yellow wing-bars give a striking appearance to this dainty specimen. Its winter and summer plumage are the same; whereas its American congener, in its sober winter garb of chocolate-brown, would never be recognized by those who only know of its bright yellow dress donned in April. The European species is the more abundant hereabouts this winter, although not hardier than the other. The "live stock" of the Park, consisting chiefly of swans, ducks, and geese, are wintered in a small basin at the end of the lake. It is amusing, on a breezy day, to see half a dozen swans floating, with heads laid back under the wing, doubtless asleep, and drifting about in the wind, like so many dismasted yachts. I have never been so struck with the fact that the effect of any object depends so largely upon its surroundings, as in looking at the swans. A pair of them on a great lake look large and imposing; twenty of them huddled together in a little basin look contemptibly small.  White-Breasted Nuthatches As one waiting for the morning looks eagerly for the first faint flush in the east, so the naturalist in this latitude by the middle of February begins to strain eye and ear for the earliest signs of spring. These tokens are found in a slight increase of some of the birds, in their passing from mere call-notes to twitters, and in an occasional sporadic song, like a spring-flower caught blooming beneath the snow. On the 16th snow-birds began to twitter, the song sparrow broke forth into melody, and high on a branch, its bright, ruddy breast never more beautiful and welcome, appeared the first robin of the season. In these days what a faint undercurrent of life now and then bubbles to the surface; just as in a mountainous country, long before sunrise, peak after peak is softly tipped with rosy light. These are delusive days. A whiff of spring to-day gets buried under two feet of snow tomorrow. Yet one feels that things are not quite as they were before. It is the magic sound of the earliest song sparrow that strikes the first blow at winter's fetters, and ever after hope will blossom on amid the snow and ice. Later came a flock of cedar-birds, also called cherry-birds and wax-wings, an unusually attractive specimen, although not brilliantly attired. Its head is conspicuously crested, the whole body of a soft and rich light-brown color, and its form is particularly graceful. The tip of the tail is yellow, and the name of wax-wing is due to the presence on the wings and sometimes on the tail of small appendages resembling bits of red sealing-wax in mature specimens. It is not known what purpose this peculiarity serves, but it is hazardous to affirm that it is merely an ornamental excrescence. It winters and summers throughout the United States, although retiring somewhat to the south in cold weather. There are only three species of wax-wings in the world, two of them in North America, the third in Japan. The other North American species is called the Bohemian or Northern waxwing. Its southern boundary about coincides with the northern tier of States, and, except that it is slightly larger than the other (our own being about seven inches long, and the Bohemian about eight), and with a slightly different tinge of brown, it is scarcely distinguishable from the cedar-bird. It is very common for any type of bird to have distinct varieties in north and south, and often in east and west. Thus among the more familiar birds we find a northern and a southern variety of the chickadee, the wren, the shrike, and the nuthatch, although the range of the two nuthatches differs less. East and west also have their counterparts in sparrows, bluebirds, robins, and many others. The western robin much resembles the eastern, but has a black band across the breast. In these cases the difference seems to be more in plumage than in habits. It will be one of the most interesting discoveries in regard to birds when we learn the causes that differentiate a genus into its species, causes which it is to be presumed are of the same nature, though not on so broad a scale, as those which from the original type of bird have produced classes, orders, families, and genera. The vocal powers of the cedar-bird are very limited, as it can produce only a faint whistle or lisp, much like a note sometimes produced by the robin, but not so asthmatic. A farmer and a naturalist look at objects from totally different points of view, and what commands the admiration of the latter may excite only the contempt of the former. The cedar-bird is a case in point; and its grace and color count for nothing with the brawny agriculturist who finds it plundering his cherry-trees. As regards a bird's reputation, Shakespeare's words are often true, "The evil that it does lives after it, the good is oft interred with its bones," which is as applicable to a bird as to a man. The theft of a few cherries or other fruit is an obvious fact, which the owner is not likely to forget; but the same bird's destruction of thousands of noxious insects, which are its staple diet, is not charged to its credit. The ravages of all the birds put together are but a petty annoyance compared with the immeasurable advantage of their presence in orchard, garden, and field. Years after the event, the ornithologist will tell you the precise spot where he discovered a new species, or first heard its song, and even what part of the day it was, and whether the sun was shining. The whole atmosphere of the scene is woven into the memory, and is suggested instantly, just as the faintest odor will sometimes recall the scenes of long ago. Thus I shall never forget the first song of the European goldfinch as it greeted the morning sun on the last day of February. Much as it resembles that of the American species it is distinctly different — so rich, liquid, and bubbling. The captious critic would say it is not all that could be desired — nothing is, for that matter — for with all its luscious and exuberant qualities it is characterless as regards form, as in our own species, but without the wiriness and undertone of petulance so often found in the latter. It is a most valuable accession to the avifauna of this country, and may it live and thrive, and never regret its translation to these shores. Leaving the finch to its own jubilation, I soon heard the sharp chuck, uttered singly, of the downy woodpecker. These woodpeckers are not singers, even in the most charitable construction of the term, and it is difficult to interpret their state of mind from the sounds they make. Doubtless he was as happy as the finch, only lacking the gift to express himself; like the swans, that plainly feel the exhilaration of spring warmth as much as anybody, and wax exceedingly vociferous if not melodious thereat. Farther on the simple carol of the song sparrow rose on the air; but the "white-throats," whose time has not yet come, were busying themselves silently. A pair of robins crossed my path; and the handsome cardinal, like a presiding genius in the scene, was flitting from tree to tree; while the little chickadee was as full of pranks as the irrepressible youngest child in the family. These were the auspicious premonitions of spring that I found on the 28th of February. But the calendar is wrong in saying that spring comes in with March. For three weeks longer night triumphs over day. But such unwonted throbs of life are not prompted by old Boreas. Already the eastern sky shows a peculiar, perhaps half-imagined glow, and there is a balmy presentiment abroad. |