|

Once there was a cat, and a

parrot. And they had agreed to ask each other to dinner, turn and turn

about:

first the cat should ask the parrot, then the parrot should invite the

cat, and

so on. It was the cat's turn first.

Now the cat was very mean.

He provided nothing at all for dinner except a pint of milk, a little

slice of

fish, and a biscuit. The parrot was too polite to complain, but he did

not

have a very good time.

When it was his turn to

invite the cat, he cooked a fine dinner. He had a roast of meat, a pot

of tea,

a basket of fruit, and, best of all, he baked a whole clothes-basketful of little cakes! -- little, brown, crispy,

spicy cakes! Oh, I should say as many as five hundred. And he put four

hundred

and ninety-eight of the cakes before the cat, keeping only two for

himself.

Well, the cat ate the roast, and drank the tea, and sucked the fruit,

and then

he began on the pile of cakes. He ate all the four hundred and

ninety-eight

cakes, and then he looked round and said: --

"I'm hungry; haven’t

you anything to eat?"

"Why," said the

parrot, "here are my two cakes, if you want them?"

The cat ate up the two

cakes, and then he licked his chops and said, "I am beginning to get an

appetite; have you anything to eat?"

"Well, really,"

said the parrot, who was now rather angry, "I don't see anything more,

unless you wish to eat me!" He thought the cat would be ashamed when he

heard that - but the cat just looked at him and licked his chops again,

-- and

slip! slop! gobble! down his throat went the parrot!

Then the cat started down

the street. An old woman was standing by, and she had seen the whole

thing,

and she was shocked that the cat should eat his friend. "Why, cat!"

she said, "how dreadful of you to eat your friend the parrot!"

"Parrot, indeed!"

said the cat. "What's a parrot to me? -- I've a great mind to eat you,

too." And -- before you could say "Jack Robinson" -- slip!

slop! gobble! down went the old woman!

Then the cat started down

the road again, walking like this, because he felt so fine. Pretty soon

he met

a man driving a donkey. The man was beating the donkey, to hurry him

up, and

when he saw the cat he said, "Get out of my way, cat; I'm in a hurry

and

my donkey might tread on you."

"Donkey, indeed!"

said the cat, "much I care for a donkey! I have eaten five hundred

cakes,

I've eaten my friend the parrot, I've eaten an old woman, -- what's to

hinder

my eating a miserable man and a donkey?"

And slip! slop! gobble! down

went the old man and the donkey.

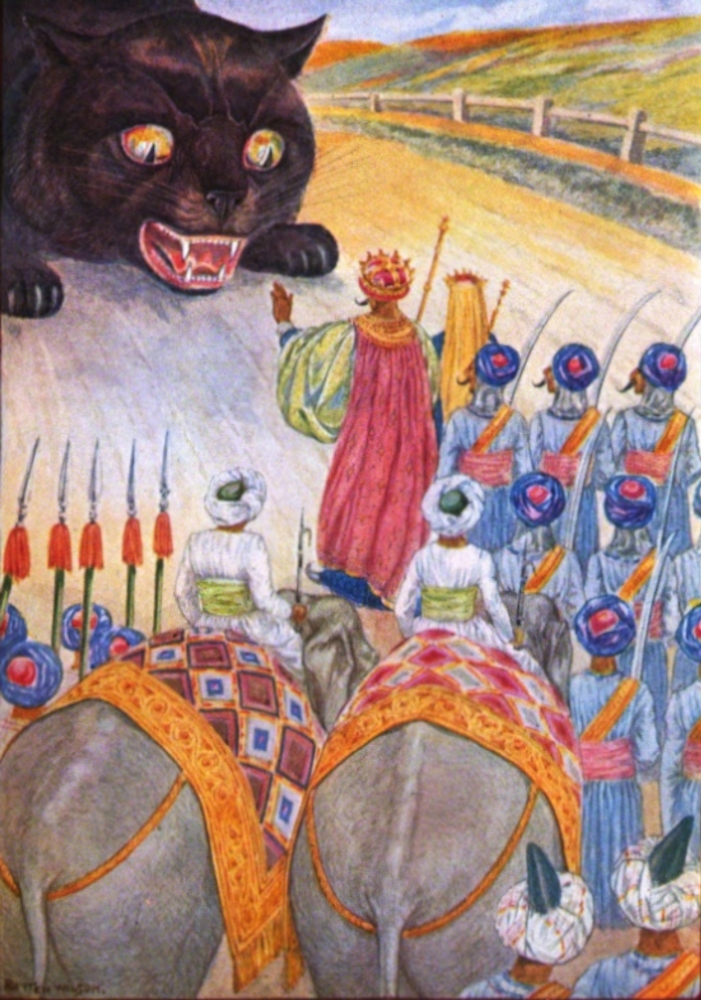

Then the cat walked on down

the road, jauntily, like this. After a little, he met a procession,

coming that

way. The king was at the head, walking proudly with his newly married

bride,

and behind him were his soldiers, marching, and behind them were ever

and ever

so many elephants, walking two by two. The king felt very kind to

everybody,

because he had just been married, and he said to the cat, "Get out of

my

way, pussy, get out of my way, -- my elephants might hurt you."

GET

OUT OF MY WAY, PUSSY

GET

OUT OF MY WAY, PUSSY

"Hurt me!" said

the cat, shaking his fat sides. "Ho, ho! I've eaten five hundred

cakes,

I've eaten my friend the parrot, I've eaten an old woman, I've eaten a

man and

a donkey; what's to hinder my eating a beggarly king?"

And slip! slop! gobble! down

went the king; down went the queen; down went the soldiers, -- and down

went

all the elephants!

Then the cat went on, more

slowly; he had really had enough to eat, now. But a little farther on

he met

two land-crabs, scuttling along in the dust. "Get out of our way,

pussy," they squeaked.

"Ho, ho, ho!"

cried the cat in a terrible voice.

"I've eaten five hundred

cakes, I've eaten my friend the parrot, I've eaten an old woman, a man

with a

donkey, a king, a queen, his men-at-arms, and all his elephants; and

now I'll

eat you too."

And slip! slop! gobble! down

went the two land-crabs.

When the land-crabs got down

inside, they began to look around. It was very dark, but they could see

the

poor king sitting in a corner with his bride on his arm; she had

fainted. Near

them were the men-at-arms, treading on one another's toes, and the

elephants

still trying to form in twos, -- but they couldn’t because there was

not room.

In the opposite corner sat the old woman, and near her stood the man

and his donkey.

But in the other corner was a great pile of cakes, and by them perched

the

parrot, his feathers all drooping.

"Let's get to

work!" said the land-crabs. And snip, snap, they began to make a little

hole in the side, with their sharp claws. Snip, snap, snip, snap, --

till it

was big enough to get through. Then out they scuttled.

Then out walked the king,

carrying his bride; out marched the men-at-arms; out tramped the

elephants, two

by two; out came the old man, beating his donkey; out walked the old

woman,

scolding the cat; and last of all, out hopped the parrot, holding a

cake in

each claw. (You remember, two cakes was all he wanted?)

But the poor cat had to

spend the whole day sewing up the hole in his coat!

THE FIRE-BRINGER

This is the Indian story of

how fire was brought to the tribes. It was long, long ago, when men and

beasts

talked together with understanding, and the gray Coyote was friend and

counselor of man.

There was a Boy of the tribe

who was swift of foot and keen of eye, and he and the Coyote ranged the

wood

together. They saw the men catching fish in the creeks with their

hands, and

the women digging roots with sharp stones. This was in summer. But when

winter

came on, they saw the people running naked in the snow, or huddled in

caves of

the rocks, and most miserable. The Boy noticed this, and was very

unhappy for

the misery of his people.

"I do not feel

it," said the Coyote.

"You have a coat of

good fur," said the Boy, "and my people have not."

"Come to the

hunt," said the Coyote.

"I will hunt no more,

till I have found a way to help my people against the cold," said the

Boy.

"Help me, O Counselor!"

Then the Coyote ran away,

and came back after a long time; he said he had found a way, but it was

a hard

way.

"No way is too

hard," said the Boy. So the Coyote told him that they must go to the

Burning Mountain and bring fire to the people.

"What is fire?"

said the Boy. And the Coyote told him that fire was red like a flower,

yet not

a flower; swift to run in the grass and to destroy, like a beast, yet

no beast;

fierce and hurtful, yet a good servant to keep one warm, if kept among

stones

and fed with small sticks.

"We will get this

fire," said the Boy.

First the Boy had to

persuade the people to give him one hundred swift runners. Then he and

they and

the Coyote started at a good pace for the faraway Burning Mountain. At

the end

of the first day's trail they left the weakest of the runners, to wait;

at the

end of the second, the next stronger; at the end of the third, the

next; and so

for each of the hundred days of the journey; and the Boy was the

strongest

runner, and went to the last trail with the Counselor. High mountains

they

crossed, and great plains, and giant woods, and at last they came to

the Big

Water, quaking along the sand at the foot of the Burning Mountain.

It stood up in a high peaked

cone, and smoke rolled out from it endlessly along the sky. At night,

the Fire

Spirits danced, and the glare reddened the Big Water far out.

There the Counselor said to

the Boy, "Stay thou here till I bring thee a brand from the burning;

be

ready and right for running, for I shall be far spent when I come

again, and

the Fire Spirits will pursue me."

Then he went up the

mountain; and the Fire Spirits only laughed when they saw him, for he

looked so

slinking, inconsiderable, and mean, that none of them thought harm from

him.

And in the night, when they were at their dance about the mountain, the

Coyote

stole the fire, and ran with it down the slope of the Burning Mountain.

When

the Fire Spirits saw what he had done they streamed out after him, red

and angry,

with a humming sound like a swarm of bees. But the Coyote was still

ahead; the

sparks of the brand streamed out along his flanks, as he carried it in

his

mouth; and he stretched his body to the trail.

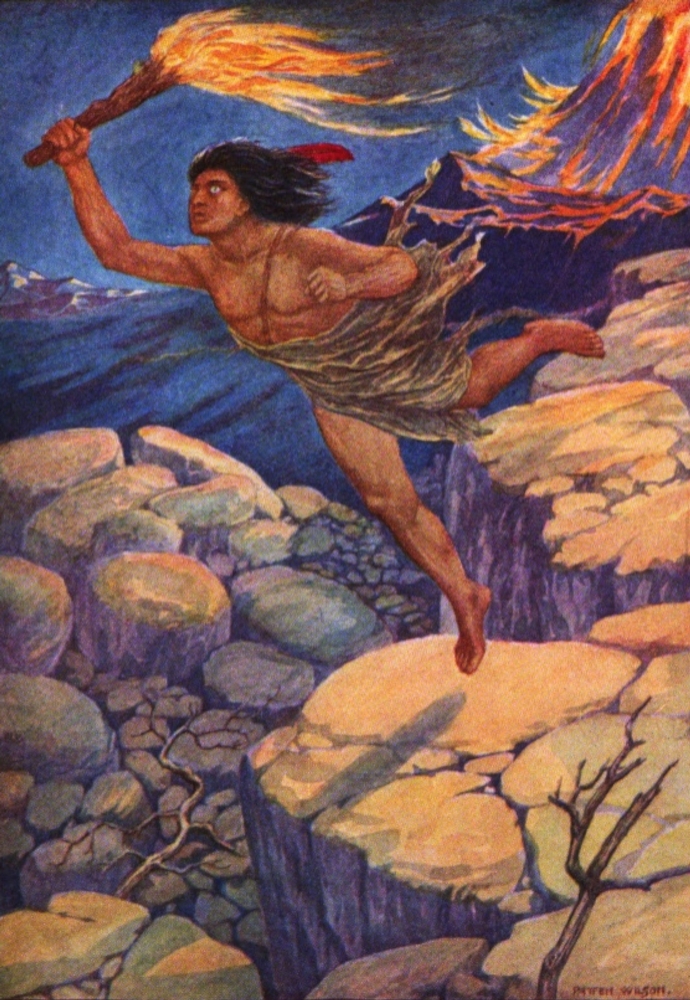

The Boy saw him coming, like

a falling star against the mountain; he heard the singing sound of the

Fire

Spirits close behind, and the laboring breath of the Counselor. And

when the

good beast panted down beside him, the Boy caught the brand from his

jaws and

was off, like an arrow from a bent bow. Out he shot on the homeward

path, and

the Fire Spirits snapped and sung behind him. But fast as they pursued

he fled

faster, till he saw the next runner standing in his place, his body

bent for

the running. To him he passed it, and it was off and away, with the

Fire Spirits

raging in chase.

So it passed from hand to

hand, and the Fire Spirits tore after it through the scrub, till they

came to

the mountains of the snows; these they could not pass. Then the dark,

sleek

runners with the backward streaming brand bore it forward, shining

star-like in

the night, glowing red in sultry noons, violet pale in twilight glooms,

until

they came in safety to their own land.

And there they kept it among

the stones and fed it with small sticks, as the Counselor advised; and

it kept

the people warm.

Ever after the Boy was

called the Fire-Bringer; and ever after the Coyote bore the sign of the

bringing, for the fur along his flanks was singed and yellow from the

flames

that streamed backward from the brand.

THE

FIRE SPIRITS TORE AFTER IT ... TILL THEY CAME TO THE MOUNTAINS OF THE

SNOWS

THE BURNING OF THE RICE

FIELDS

Once there was a good old

man who lived up on a mountain, far away in Japan. All round his little

house

the mountain was flat, and the ground was rich; and there were the rice

fields

of all the people who lived in the village at the mountain's foot.

Mornings and

evenings, the old man and his little grandson, who lived with him, used

to look

far down on the people at work in the village, and watch the blue sea

which

lay all round the land, so close that there was no room for fields

below, only

for houses. The little boy loved the rice fields, dearly, for he knew

that all

the good food for all the people came from them; and he often helped

his

grandfather watch over them. One day, the grandfather was standing

alone,

before his house, looking far down at the people, and out at the sea,

when,

suddenly, he saw something very strange far off where the sea and sky

meet.

Something like a great cloud was rising there, as if the sea were

lifting

itself high into the sky. The old man put his hands to his eyes and

looked

again, hard as his old sight could. Then he turned and ran to the house.

"Yone, Yone!" he

cried, "bring a brand from the hearth!"

The little grandson could

not imagine what his grandfather wanted of fire, but he always obeyed,

so he

ran quickly and brought the brand. The old man already had one, and was

running

for the rice fields. Yone ran after. But what was his horror to see his

grandfather thrust his burning brand into the ripe dry rice, where it

stood.

"Oh, Grandfather,

Grandfather!" screamed the little boy, "what are you doing?"

"Quick, set fire!

Thrust your brand in!" said the grandfather.

Yone thought his dear

grandfather had lost his mind, and he began to sob; but a little

Japanese boy

always obeys, so though he sobbed, he thrust his torch in, and the

sharp flame

ran up the dry stalks, red and yellow. In an instant, the field was

ablaze, and

thick black smoke began to pour up, on the mountain side. It rose like

a cloud,

black and fierce, and in no time the people below saw that their

precious rice

fields were on fire. Ah, how they ran! Men, women, and children climbed

the

mountain, running as fast as they could to save the rice; not one soul

stayed

behind.

And when they came to the mountain

top, and saw the beautiful rice-crop all in flames, beyond help, they

cried

bitterly, "Who has done this thing? How did it happen?"

"I set fire," said

the old man, very solemnly; and the little grandson sobbed,

"Grandfather

set fire." But when they came fiercely round the old man, with "Why?

Why?" he only turned and pointed to the sea. "Look!" he said.

They all turned and looked.

And there, where the blue sea had lain, so calm, a mighty wall of

water,

reaching from earth to sky, was

rolling in. No one could

scream, so terrible was the sight. The wall of water rolled in on the

land,

passed quite over the place where the village had been, and broke, with

an

awful sound, on the mountain-side. One wave more, and still one more,

came; and

then all was water, as far as they could look, below; the village where

they

had been was under the sea.

But the people were all

safe. And when they saw what the old man had done, they honored him

above all

men for the quick wit which had saved them all from the tidal wave.

THE STORY

OF JAIRUS'

DAUGHTER

Once, while Jesus was

journeying about, he passed near a town where a man named Jairus lived.

This

man was a ruler in the synagogue, and he had just one little daughter,

about

twelve years of age. At the time that Jesus was there the little

daughter was

very sick, and at last she lay a-dying.

Her father heard that there

was a wonderful man near the town, who was healing sick people whom no

one else

could help, and in his despair he ran out into the streets to search

for him.

He found Jesus walking in the midst of a crowd of people, and when he

saw him

he fell down at Jesus' feet and besought him to come into his house, to

heal

his daughter. And Jesus said, yes, he would go with him. But there were

so many

people begging to be healed, and so many looking to see what happened,

that

the crowd thronged them, and kept them from moving fast. And before

they

reached the house one of the man's servants came to meet them, and

said,

"Thy daughter is dead; trouble not the master to come farther."

But instantly Jesus turned

to the father and said, "Fear not; only believe, and she shall be made

whole." And he went on with Jairus, to the house.

When they came to the house,

they heard the sound of weeping and lamentation; the household was

mourning

for the little daughter, who was dead. Jesus sent all the strangers

away from

the door, and only three of his disciples and the father and mother of

the

child went in with him. And when he was within, he said to the mourning

people,

"Weep not; she is not dead; she sleepeth."

When he had passed, they

laughed him to scorn, for they knew that she was dead.

Then Jesus left them all,

and went alone into the chamber where the little daughter lay. And when

he was

there, alone, he went up to the bed where she was, and bent over her,

and took

her by the hand. And he said, "Maiden, arise."

And her spirit came unto her

again! And she lived and grew up in her father's house.

TARPEIA

There was once a girl named

Tarpeia, whose father was guard of the outer gate of the citadel of

Rome. It

was a time of war, -- the Sabines were besieging the city. Their camp

was close

outside the city wall.

Tarpeia used to see the

Sabine soldiers when she went to draw water from the public well, for

that was

outside the gate. And sometimes she stayed about and let the strange

men talk

with her, because she liked to look at their bright silver ornaments.

The

Sabine soldiers wore heavy rings and bracelets on their left arms, --

some wore

as many as four or five.

The soldiers knew she was

the daughter of the keeper of the citadel, and they saw that she had

greedy

eyes for their ornaments. So day by day they talked with her, and

showed her

their silver rings, and tempted her. And at last Tarpeia made a

bargain, to

betray her city to them. She said she would unlock the great gate and

let them

in, if they would give her what

they wore on their left arms.

The night came. When it was perfectly dark and

still, Tarpeia stole from her bed, took the great key from its place,

and

silently unlocked the gate which protected the city. Outside, in the

dark,

stood the soldiers of the enemy, waiting. As she opened the gate, the

long

shadowy files pressed forward silently, and the Sabines entered the

citadel.

As the first man came

inside, Tarpeia stretched forth her hand for her price. The soldier

lifted high

his left arm. "Take thy reward! " he said, and as he spoke he hurled

upon her that which he wore upon it. Down upon her head crashed -- not

the

silver rings of the soldier, but the great brass shield he carried in

battle!

She sank beneath it, to the

ground.

"Take thy reward,"

said the next; and his shield rang against the first.

"Thy reward," said

the next -- and the next -- and the next -- and the next; every man

wore his

shield on his left arm.

So Tarpeia lay buried

beneath the reward she had claimed, and the Sabines marched past her

dead body,

into the city she had betrayed.

THE JUDGMENT OF MIDAS

The Greek god Pan, the god

of all out-of-doors, was a great musician. He played on a pipe of

reeds. And

the sound of his reed-pipe was so sweet that he grew proud, and

believed

himself greater than the chief musician of the gods, Apollo, the

sun-god. So he

challenged great Apollo to make better music than he.

Apollo consented to the

test, to punish Pan's vanity, and they chose the mountain Tmolus for

judge,

since no one is so old and wise as the hills.

When Pan and Apollo came

before Tmolus, to play, their followers came with them, to hear. One of

the

followers of Pan was a mortal named Midas.

First Pan played; he blew on

his reed-pipe, and out came a tune so wild and yet so coaxing that the

birds

hopped from the trees to get near; the squirrels came running from

their holes;

and the very trees swayed as

if they wanted to dance. The

fauns laughed aloud for joy as the melody tickled their furry little

ears. And

Midas thought it the sweetest music in the world. Then Apollo rose. His

hair

shook drops of light from its curls; his robes were like the edge of

the sunset

cloud; in his hands he held a golden lyre. And when he touched the

strings of

the lyre, such music stole upon the air as never god nor mortal heard

before.

The wild creatures of the wood crouched still as stone; the trees held

every

leaf from rustling; earth and air were silent as a dream. To hear such

music

cease was like bidding farewell to father and mother. When the charm

was

broken, all his hearers fell at Apollo's feet and proclaimed the

victory his.

But Midas would not. He alone would not admit that the music was better

than

Pan's.

"If thine ears are so

dull, mortal," said Apollo, "they shall take the shape that suits

them." And he touched the ears of Midas. And straightway the dull ears

grew long, pointed, and furry, and they turned this way and that. They

were the

ears of an ass!

For a long time Midas

managed to hide the tell-tale ears from every one; but at last a

servant

discovered the secret. He knew he must not tell, yet he could not bear

not to;

so one day he went into the meadow, scooped a little hollow in the

turf, and

whispered the secret into the earth. Then he covered it up again, and

went

away. But, alas, a bed of reeds sprang up from the spot and whispered

the

secret to the grass. The grass told it to the tree-tops, the tree-tops

to the

little birds, and they cried it all abroad.

And to this day, when the

wind sets the reeds nodding together, they whisper, laughing, "Midas

has

the ears of an ass! Oh, hush, hush!"

|