|

Click Here to return to Boston Illustrated Content Page Click Here to return to Previous Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

Click Here to return to Boston Illustrated Content Page Click Here to return to Previous Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

VII. NEW BOSTON AND THE SUBURBS, Continued.

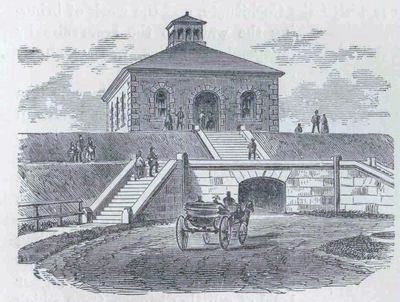

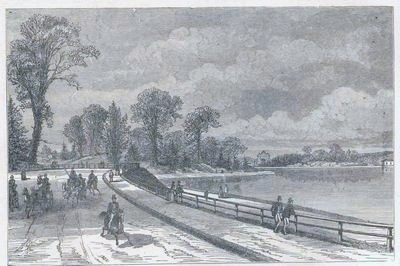

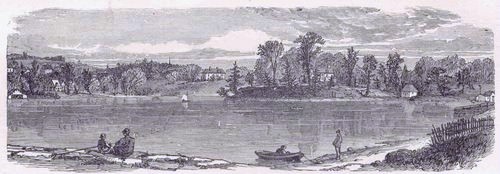

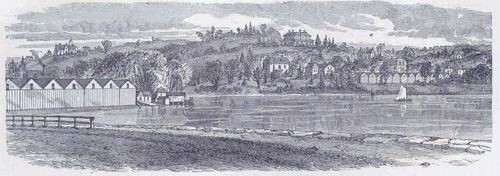

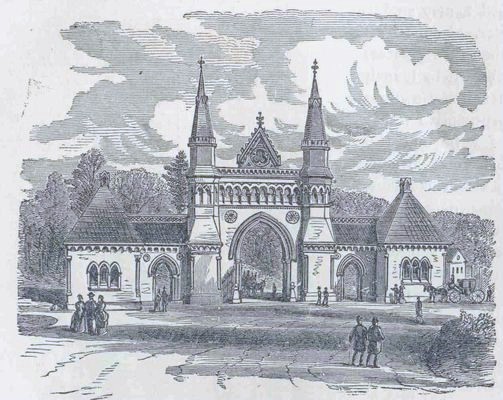

The history of the Boston Water-Works belongs properly in a description of the Brighton District, where the most extensive and costly work is. The original public introduction of water, which dates from October 25, 1848, is mentioned in the description of the Common in preceding pages. The growth of the city has been so rapid that what was originally calculated to be a sufficient supply of water for half a century was, in a few years, found to be inadequate. Again and again have measures been taken to make good the deficiency. In 1872 a comprehensive scheme was entered upon which, it was hoped, would avert for an indefinite period all fears of a water famine. That this hope has been disappointed and that a still more extensive and expensive scheme has been adopted, namely the introduction of the use of. the Sudbury River, is matter of history.  Consumptives’ Home, Dorchester District. The necessity for building a new reservoir, for the purpose of storing the water that usually ran to waste over the dam at Lake Cochituate during and after the spring and fall freshets, was urged by the Water Board in 1863. In 1865 the Legislature gave the necessary authority to the city; purchases of land were made, and the work begun. More than two hundred acres of land, costing about $120,000, were deeded to the city before the reservoir was finished. Like the Brookline Reservoir, it constituted a natural basin. It is five miles from the Boston City Hall, and one mile from the Brookline Reservoir. It lies wholly in the Brighton District n ear Chestnut Hill, from which it derives its name. It is, in fact, a double reservoir, being divided by a water-tight dam into two basins of irregular shape. The surface of water in both is about one hundred and twenty-five acres, and when filled to their fullest capacity the two basins will hold nearly eight hundred million gallons. As we have said, this addition to the works has been found inadequate, and in 1872 authority was obtained for the city to take water from the Sudbury River. A temporary supply was procured by connecting the river with Lake Cochituate, and the work of bringing the water to the reservoirs by independent mains was promptly carried out.  Entrance to the Reservoir grounds.  Gate House, Chestnut Hill.  The Drive, on the Margin of the small Reservoir. The Chestnut Hill Reservoir is a great pleasure resort. A beautiful drive-way, varying from sixty to eighty feet in width, surrounds the entire work. In some parts the road runs along close to the embankment, separated from it only by the beautiful gravelled walk with the sodding on either side. Elsewhere it leaves the embankment and rises to a higher level at a little distance, from which an uninterrupted view of the entire reservoir can be had. The scenery in the neighborhood is so varied that it would of itself make this region a delightful one for pleasure driving, without the added attractions of the charming sheet of water, the graceful curvatures of the road, and the neat, trim appearance of the greensward that lines it throughout its entire length.  The Drive, showing the Large Reservoir. Before the introduction of water from Lake Cochituate the city was dependent upon wells and springs, and upon Jamaica Pond, in West Roxbury, which is now Ward Twenty-three of Boston. A company was incorporated in 1795 to bring water into Boston from that source, and its powers were enlarged by subsequent acts. It was for a long time a bad investment for the shareholders. Afterwards the company had a greater degree of prosperity, and at one time it supplied at least fifteen hundred houses in Boston. The water was conveyed through the streets by four main pipes, consisting of pine logs. Two of these were of four inches, and two of three inches, bore. The water thus brought into the city was carried nearly as far north as State Street. In 1840 an iron main, ten inches in diameter, was laid through the whole length of Tremont Street to Bowdoin Square. But the prospective wants of the city were far beyond the capacity of Jamaica Pond to supply, and the Lake Cochituate enterprise not only prevented the aqueduct company from enlarging its operations, but rendered all its outlay in Boston useless and valueless. The city, however, made compensation by purchasing the franchise and property for the sum of $45,000, in 1851. The property, minus the franchise, which the city of course wished to extinguish, was sold in 1856, for $ 32,000. At present the chief practical use of Jamaica Pond is to furnish in winter a large quantity of ice, which is cut and stored in the large houses on its banks, for consumption in the warm weather. It is a great resort for young and some older people in the winter for skating. Handsome estates line its banks, and the drive around it is one of the most beautiful of the many which make the suburbs of Boston so attractive to its own citizens and to strangers. In summer there is much pleasure sailing and rowing on the pond, and in past years there have been several interesting regattas upon it.  Jamaica Pond, North View.  Jamaica Pond, South Side. Forest Hills Cemetery, also in the West Roxbury district was originally established by the city of Roxbury, of which the town at the time formed a part. It was subsequently conveyed to the predecessors of the present proprietors. It is a little larger in territory than Mount Auburn. It contains a great number of interesting memorials. The burial lot of the Warren family is on the summit of Mount Warren. T h e remains of General Joseph Warren, who fell at Bunker Hill, have been taken from the Old Granary Burying-Ground in Boston, and reinterred in this cemetery. Within recent years an impressive receiving-tomb has been built at Forest Hills. The portico is nearly thirty feet square, and is built in the Gothic style of architecture in Concord granite. Its appearance is massive, without being cumbersome. Within there are two hundred and eighty-six catacombs, each for a single coffin, which are closely sealed up after an interment. The entrance gateway to Forest Hills Cemetery is a unique and striking structure of Roxbury stone and Caledonia freestone. The inscription upon the face of the outer gateway is, — “I AM THE RESURRECTION AND THE LIFE,”

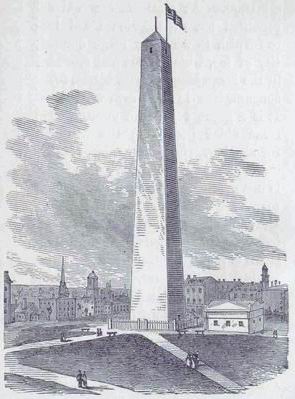

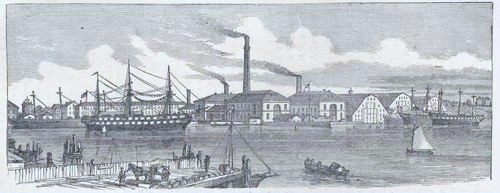

in golden letters. On the inner face is in similar letters the inscription,— “HE THAT KEEPETH THEE WILL NOT SLUMBER.”  Entrance to Forest Hills. The grounds of the cemetery, like those of Mount Auburn, are exceedingly picturesque, the variety of hill and dale, greensward, thickets of trees, pleasant sheets of water, and rocky eminences, making the place an attractive spot. The Charlestown district is noted for containing Bunker Hill, as interesting a spot as Revolutionary history can boast. And the monument that crowns the hill is so conspicuous as hardly to require that attention should be directed to it. The event it celebrates and the consequences of that event, the appearance of this imposing granite shaft, and the magnificent view of the entire surrounding country to be obtained from its observatory, are, or should be, familiar to every citizen of New England; and no visitor to Boston from more distant parts of the country is likely to return home without ascending the monument, as a good patriot. The oration delivered by Daniel Webster at the dedication of the monument on the anniversary of the battle of Bunker Hill, the 17th of June, 1843, has been declaimed by many a school-boy.  Bunker Hill Monument Within the monument grounds, standing in the main path, is the new bronze statue of Colonel William Prescott, by W. W. Story. This is of heroic size, and is intended to depict Prescott the moment that he uttered the warning words, to the patriot soldiers, “Don’t fire until I tell you; don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.” The statue was unveiled with formal ceremonies on June 17, 1881, when Robert C. Winthrop delivered an oration. No visitor to Charlestown should leave it until he has visited the United States Navy Yard, established by the government in the year 1800. The yard has since been very greatly enlarged, and extensive and costly buildings have been erected upon it. The dry-dock, which was begun in July, 1827, and completed six years later, is a most substantial work of granite masonry, 341 feet long, 80 feet wide, and 30 feet deep, which cost, even in those days of low prices, $675,000. The granite ropewalk too, the finest structure of the kind in the country, and a quarter of a mile in length, will not fail to attract attention. Several of the largest vessels of our old navy were built at this yard. Of late, while the government has been reducing, rather than increasing, its naval force, the work here has been confined chiefly to repairs upon old vessels, and the busy activity of past years is no longer seen. Its sale has been agitated in recent years.  The Navy Yard, from East Boston. The United States Marine Hospital at Chelsea, which appears on the right in the background of the sketch of the Navy Yard, is a large and handsome structure upon the crest of a high hill, near the mouth of the Mystic River. This institution, as well as the Naval Hospital, at the foot of the same hill, was erected and is maintained by the general government for the benefit of invalid sailors. The situation is salubrious, and the prospect from the Marine Hospital, overlooking as it does the harbor and two or three cities, is very fine. No other city in the country can boast such suburbs as Boston has. For extent and beauty, they are unrivalled. The picturesque hills, separated by beautifully winding rivers, make, of themselves, an ever-varied landscape. Art has added greatly to the beauties which nature has so lavishly scattered. Many available sites for fine country residences have been occupied, and all that wealth could do to improve upon natural attractions has been done. But this is not all. Large cities and a score of flourishing towns have sprang up, where city and country are pleasantly commingled; and everywhere throughout the large district of which Boston is the centre may be seen evidences of industry and thrift, excellent roads, neat fences and hedges, thriving gardens and orchards, comfortable, tastefully built, and well-painted houses. Passing into Cambridge we must first notice it as the site of the most famous university in the country. It was but six years after the settlement of Boston that the General Court appropriated four hundred pounds for the establishment (of a school or college at Newtown, as Cambridge was then called. As this sum was equal to a whole year’s tax of the entire colony, we may infer in what estimation the earliest colonists held a liberal education. Two years after, the institution received the liberal bequest of eight hundred pounds from the estate of the Rev. John Harvard, an English clergyman, who died at Charlestown in 1638. The General Court, in consequence of this bequest, named the college after its generous benefactor, and changed the name of the town where it was located to Cambridge, Mr. Harvard having been educated at Cambridge in old England. The college was thus placed on a firm foundation; and by good management and the prevalence of liberal ideas, under the fostering care of the Colony and the State, and the almost lavish generosity of alumni and other friends, it has assumed and steadily maintained the leading position among the colleges of the country, its only rival being Yale. The college long ago became a university. Schools of law, medicine, dentistry, theology, science, mining, and agriculture, have been established in connection with it, each endowed with its own funds, and each independent of all the others, except that all are under one general management. The college yard contains a little more than twenty-two acres, and nearly the whole available space is already occupied by the numerous buildings required by an institution of such magnitude. Some of the more recently erected dormitories are fine specimens of architecture, and admirably suited to the use for which they were designed. Among these are Thayer Hall, an imposing structure containing sixty-eight suites of rooms, built in 1870, at a cost of $115,000; Grays Hall, a long five-story brick building, erected in 1863, and containing fifty-two suites; and Matthews Hall, an ornate Gothic edifice, which was built in 1872, at a cost of $120,000. An important change was effected in 1865, after long discussion, in the government of the university; the overseers, constituting the second and more numerous branch of the university legislature, were originally the Governor and Deputy Governor, with all the magistrates, and the ministers of the six adjoining towns. After numerous changes, which were, however, only changes in the manner of selecting the clergymen who should constitute this board, the power of choosing the overseers was, in 1851, vested in the Legislature. All this system has since been abolished. The graduates of the college now choose the entire board. There are about 1,900 students, in all branches of the university, and 160 professors and teachers of various grades. Without speaking of the various society libraries, the university has nine minor libraries connected with various departments, containing nearly 80,000 volumes; while the college library has about 260,000 bound volumes. The latter is in Gore Hall, a Gothic building of Quincy granite, erected in 1841, and reinforced in 1877 by a very large fire-proof extension of granite and iron. There are but two libraries in America larger than this one, those of the city of Boston and of Congress; and its privileges are generously extended to men of letters outside of the university jurisdiction.  Gore Hall, Harvard College. |