| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2017 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER VIII. DUBLIN AND ABOUT THERE THE environment of Dublin, so far as its immediate surroundings are concerned, is exceedingly attractive to the jaded inhabitant of brick and mortar cities. Phœnix Park, belonging anciently to the Knights Templars, is more beautiful, as a city park, than those possessed by any other city of the size of Dublin in the British Isles, and is, moreover, of great extent. It is densely wooded, has lovely glades, and is plentifully stocked with herds of deer, who seem unconsciously to group themselves picturesquely at all times. It is in no sense grand, nor, indeed, are the views of the lovely country lying immediately to the southward; but the distant views of the Wicklow peaks are full of quiet, restful beauty, which must help to make life in a great centre of population, such as Dublin, livable at all seasons of the year. The Viceregal Lodge is in Phœnix Park, and near it is the spot where Lord Frederick Cavendish and Mr. Burke were walking together on the night of May 6, 1882, when they were assassinated by the “Invincibles.” The “Fifteen Acres,” where now horses are exercised, was a very favourite duelling-ground in olden times. A local description of this “bloody ground” states: “There is not a single one of its acres that has not been stained with blood over and over again, in those gray mornings of the eighteenth century, when Dublin beaux, half-sobered after a night’s debauch, used to confront one another in the dew-drenched grass, and startle the huddled herds of deer with the deadly crack of pistols at twelve paces.”

NEW GRANGE. Beyond Phœnix Park is Lucan, four miles up the Liffey, near the river’s celebrated salmon-leap. Clondalkin, six miles from Dublin, possesses one of the finest and most perfect round towers in Ireland, eighty feet in height, and forty-five in circumference at the base. The Falls of the Liffey, at Poula-Phooka, twenty miles from town, flow under a graceful viaduct. Here the foam-whitened river casts itself down a succession of rocky leaps, and through a richly wooded gorge, into the smoother plain below. This is a scenic gem, such as amateur photographers love, and its picturings are found in the album of almost every Irish traveller. Its name enshrines one of the best known of the many Celtic fairy myths, — that of the Phooka. Certainly, the wild, lofty defile of splintered rock, through which the fall leaps down, must have been exactly the sort of place to allure the goblin horse that had such an unpleasant fancy for breaking people’s necks. The legend of the Phooka is one familiar in many forms to all lovers of folk-lore. It is claimed to be of Celtic origin, but with equal assurance it is said to be Norse, and again Indian. The apparition is a weird ghost-like horse-shape, not unlike the steed which Ichabod Crane saw mounted by a headless horseman. Kingstown, seven miles from Dublin, has no great interest for the lover of artistic or historic shrines, though the view of its harbour, with its cross-channel shipping, its fishing-boats, and its long, jutting piers, composes itself gaily enough, on a bright summer’s day, into a pleasing picture. Originally named Dunleary, the town received its present title in 1821, after the departure of George IV. An obelisk, surmounted by a crown, and placed upon four stone balls, stands near the harbour entrance, and commemorates — what? The king’s coming? Not at all. He landed at Howth, and no one, apparently, thought that incident worthy of a memorial. The Kingstown obelisk commemorates his departure from his Irish dominions. This seems significant, but it will not do to condemn Irish hospitality on this score. Perhaps it is an attempt at humour. If so, it is not wholly unsuccessful. Just north of Dublin are two spots famed alike of history and legend, — at least most of the local story-tellers’ tales sound like legends, — Clontarf and Howth. As the Hill of Howth is one of the first of Ireland’s landmarks which come to the vision of the majority of visitors from England, it may perhaps be permissible to include the following lines here. They were written many years ago by a local poet whose, name is lost in obscurity, but whose verse is sufficiently apropos to-day to need no qualifying comment: “Well might an artist travel from afar,

To view the structure of a low-backed car; A downy mattress on the car is laid, The father sits beside his tender maid. Some back to back, some side to side are placed, The children in the centre interlaced. By dozens thus, full many a Sunday morn, With dangling legs the jovial crowd is borne; Clontarf they seek, or Howth’s aspiring brow, Or Leixlip smiling on the stream below.” “The Hill” is a bold peninsula at the mouth of Dublin Bay, above whose waters, and those of the Irish Sea, the rugged promontory rises to the height of 563 feet. The whole mount abounds in precipitous rocky formations, blended most artistically with fields of heather and of greensward in a manner apparently possible only in Ireland. From the cliffs over-looking the sea, the outlook embraces the counties of Dublin, Meath, and Louth; the Mourne Mountains and County Down, Ireland’s Eye and Lambay Island; while to the south loom the Wicklow Hills, Bray Head, Sugar Loaf Mountain, Dalkey Island, Kingstown Harbour, and Dublin, showing a variety of form which contrasts strangely with the placid sea, sky, and hills. Howth itself is a village of one long, rambling street, — or was; of late it has grown more pretentious, and has thereby lost some of its pristine charm. Off Howth Harbour is “Ireland’s Eye,” which in ancient works is printed Irlandsey. Thus its evolution is easily followed. The island has some fragmentary remains of the old church of St. Nessan, showing portions of a still more ancient round tower. The ancient castle of Howth is the family seat of the St. Lawrences, the Earls of Howth, who have held it since the time of their ancestor, Sir Armoric Tristram de Valence, who arrived here in the twelfth century. It is said that the family name was Tristram, and that even Sir Armoric never bore the present family title, but that a descendant or relative assumed it on the occasion of a battle won by him on St. Lawrence’s Day. The castle was in a great measure rebuilt by the twentieth Lord of Howth in the sixteenth century. It consists of an embattled range, flanked by towers. The interior of the castle is rich in historical associations, founded as it was by one of the most chivalrous of the Anglo-Norman settlers in Ireland. One sad blow was struck at the founder’s dignity by the graceless Grace O’Malley, or Granuaile, or Grana Uile, a western chieftainess, who, returning from a visit to Queen Elizabeth at London, landed at Howth and essayed to tax the hospitality of the lordly owner, who refused to give her any refreshment. Determined to have her revenge, however, and to teach hospitality to the descendant of the Saxon, she kidnapped the heir and kept him a close prisoner until a pledge was obtained from his father that on no pretence whatever were the gates of Howth Castle to be closed at the hour of dinner. A painting of the incident exists, or did exist, in the oak-panelled dining-hall of the castle. In the hall also is the two-handed sword which won that St. Lawrence’s Day battle. It measures, even in its mutilated state, five feet, seven inches, the hilt alone being twenty-two inches long. St. Mary’s Abbey, Howth, is a great ruined, roofless structure, which, in spite of its decrepitude, tells a story of great and appealing interest to the student of architecture. Its foundation by Luke, Archbishop of Dublin, dates from 1234, and it is one of those picturesque ruins which, while by no means so grand, will rank in the memory with Melrose and Muckross. As a well-preserved ruin, it still exists and shows unmistakable evidences of having been inspired by some Burgundian or Lombard architect-builder. Lying between Howth and Dublin is Clontarf, famous as the scene of Brian Boru’s victory over the Danes. Moore has perpetuated its glories in verse, thus: “Remember the glories of Brian the brave,

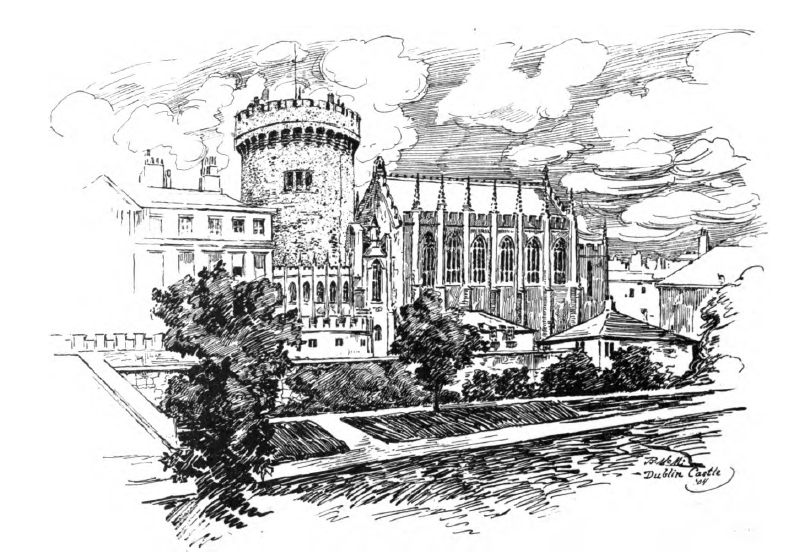

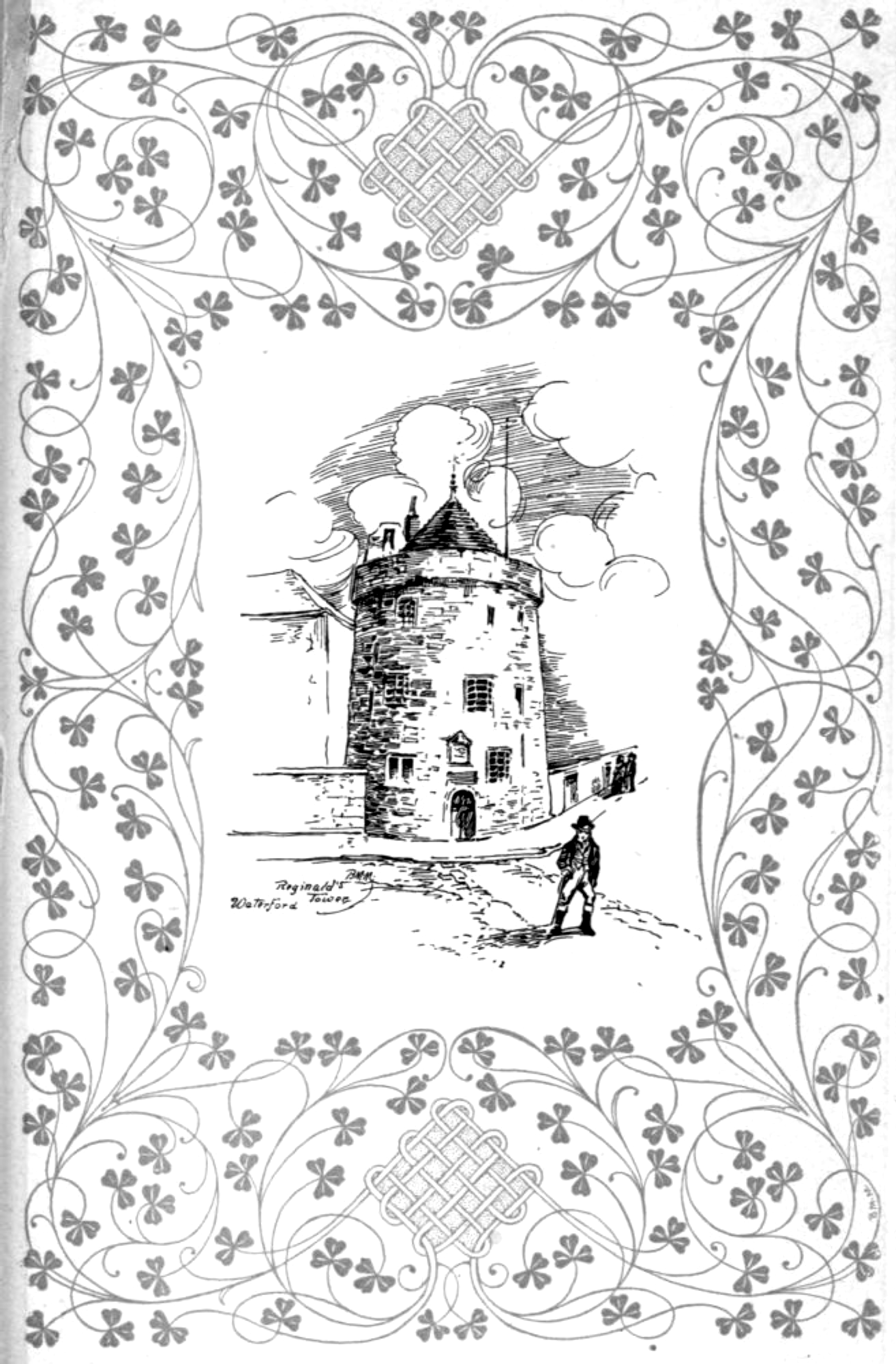

Though the days of the hero are o’er; Though lost to Mononia, and cold in the grave, He returns to Kinkora no more. That star of the field, which so often hath poured Its beam on the battle, is set; But enough of its glory remains on each sword To light us to victory yet.” Many have doubted whether the victory was really in favour of the Irish. It is generally, however, conceded to have been in their favour. Scotsmen will be interested to see the name of Lennox mentioned among the soldiers of the patriot king. An Irish manuscript, translated for the Dublin Penny Journal, after summing up the number of natives slain on the side of Brian, says: “The great stewards of Leamhue (Lennox) and Mar, with other brave Albanian Scots, the descendants of Corc, King of Munster, died in the same cause.” After the battle, great respect was shown to the body of the deceased king by his devoted followers, who looked upon him in the light almost of a saint. Wills, the historian, gives the following account of the progress of his corpse: “The body of Brian, according to his will, was conveyed to Armagh. First, the clergy of Swords in solemn procession brought it to their abbey, from thence the next morning the clergy of Damliag (Duleck) conducted it to the church of St. Kiaran. Here the clergy of Lowth (Lughmach) attended the corpse to their own monastery. The Archbishop of Armagh, with its suffragans and clergy, received the body at Lowth, whence it was conveyed to their cathedral. For twelve days and nights it was watched by the clergy, during which time there was a continual scene of prayers and devotion.” Few traces remain of this dreadful encounter, and one perforce takes a good deal on faith, as one does much of history where architectural remains are practically non-existent. An ancient preceptory of the Knights Templars, a dependency of that at Kilmainham, formerly occupied the site of Clontarf Castle, the seat of the Vernons. Dublin is the metropolitan county of Ireland, also its chief city. The city is thought to have derived its name from the “black channel” of the river Liffey, and to have communicated the name by some expansionist process to the surrounding county, which comprised the six baronies of Coolock, Balrothery, Nethercross, Castleknock, Newcastle, and Uppercross, as well as half that of Rathdown. Dublin County, unlike most other parts of Ireland, has no silver or mirror lake. In this respect it has manifestly been cheated by nature. Neither are there any of those deforming peat-bogs with which many of Ireland’s fairest lakes are surrounded. There is a great distinction between legendary and monumental remains; and, since Ireland is so full of both sorts, it behooves one to stop and think for a moment, when viewing some shrine to which his fancy has led him, whether it ever had a former, a real existence, or not. This opens a vast field to research, controversy, and soi-disant opinion. Near Dublin, on the hill called Tallaght, there are mounds — existing since time immemorial — referred to by the old historians on pre-Christian Ireland as “the mortality tombs of the people of Partholan,” who first colonized Ireland. The mounds are there, and we, perforce, have to imagine the rest, but there is good ground for believing that these grass-grown mounds, the burial-places of thousands of people, are as real and tangible memorials of the pre-Christian era in the British Isles as are anywhere to be found. The history of Dublin, like that of most capitals, has been momentous. From the second century onward, it has encountered many battles, sieges, and rebellions, and has been the centre of political activity in Ireland. For the average traveller Dublin is simply a great centre of modern life and movement; for the student of history, architecture, archæology, and such subjects it is much more. The bird of passage, then, will only be visibly affected by that which lies on the surface, or at least nearest thereto. He will see that Dublin possesses all the component luxuries of a great city; is progressive to the extent of having cut up its roadways with tram-lines, and disfigured its streets with telegraph and electric-light poles; and, in short, has all those attributes which make even the lover of life in a large city sooner or later wish to put it all behind him. The greatest novelties for the visitor are the two splendidly organized bodies of constabulary, — the Dublin policemen and the Royal Irish Constabulary. The Dublin Metropolitan Police is a fine semi-military force distinct from the Royal Irish Constabulary, only acting within the metropolitan district, and is reminiscent of foreign gendarmerie, with its dark blue and silver uniform and smart appearance. The minimum height is five feet, eleven inches, so that Dublin streets seem to be policed by a race of amiable giants. In America the same type of constable is well known. It is also well known that the “force” in America is organized on somewhat different lines from that of its brothers in Dublin. The Royal Irish Constabulary, who are to be seen in the neighbourhood of Phœnix Park (and all over the country besides), are, physically, a magnificent body of men, with as good, if not a considerably better training than “Tommy Atkins” himself. It is a curious present-day fact that Dublin, as the capital of a Catholic country, not only possesses no Catholic cathedral, but has two Protestant churches known as cathedrals. Anti-Catholic writers have long found fault with, and traced certain of Ireland’s interior troubles to, the number and power of the Catholic places of worship. That Dublin has two Protestant cathedrals has apparently escaped their notice. It is also true that not all the Protestant churches in Ireland are overflowing with congregations, but most of the Catholic places of worship are. This may mean much or little. Just what it does mean is doubtful, but it is a well-known fact, and because of this it is recorded here. Christchurch Cathedral was founded by Sigtryg Silkbeard, a Danish king who had become Christianized, and Donatus, a Danish bishop, in 1038. It was dedicated to the Holy Trinity, with the Danish name of Christchurch; later it was converted into a priory, which in turn was absorbed into an Anglo-Norman cathedral, erected by Strongbow and others on the former Danish foundation. The fabric is of much interest, although, owing to various mishaps, such as the slipping away of the peat-bog on which it was injudiciously built, the walls have many times fallen and been renewed. In Christchurch Cathedral Lambert Simnel was crowned in 1486, and mass was celebrated here during the sojourn of James II. Strongbow’s tomb is the most noted relic of the church. It has an inscription by Sir Henry Sidney, the father of Philip Sidney, referring to “This Ancyent Monument of Richard Strangbowe, called Comes Strangulensis, Lord of Chepsto and Ogny, etc.” The crypt is of interest from being mainly built up from the rude early church of the Danish founder. St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the cathedral without the walls of ancient Dublin, is larger and more imposing than Christchurch. It is cruciform in plan, and altogether a beautiful and stately structure, partaking largely after the style of the Anglo-Norman structures of England, but not those of Normandy. Founded by Comyn, the Anglo-Norman Archbishop of Dublin, in 1190, the ancient Celtic church of St. Patrick de Insula, which stood without the city walls, and was specially held in reverence from its association with the baptism of the saint, formed the nucleus of the new establishment, which was self-contained and fortified. Its exposed position, however, led it to be abandoned to the marauding natives, and the buildings fell into decay. The present cathedral is of the twelfth to fourteenth centuries. Cromwell desecrated it, as he did many others, by using it for a justice court. Great churches have ever been despoiled by fanatics in all lands. James II. went one step farther (being James II. this seems inexplicable to-day), and converted it into a stable. The restoration of this shockingly desecrated shrine (at the expense of more than £140,000) is to the credit of the family of Guinness, whose name and product is a household word throughout the world. Cromwell was a brewer, too, and supposed to have been a righteous, if stern man, but his virtues were not as great as those of his latter-day compeer. Since the visitor to Ireland is supposed to wander about with a volume of Swift’s “Life and Letters” in his hand, and to recall at appropriate times the laurelled arbour-retreat near Celbridge, where, two hundred years ago, the luckless Vanessa waited long, and often in vain, it will be well for him to contemplate the two monuments in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the one to Swift (who was Dean of St. Patrick’s), and the other to Miss Johnson, his Stella. Another curious religious shrine is the church of St. Fichan, founded in 1095 by the pious Dane whose name it bears, though the present structure dates only so far back as 1676. The square tower, however, is decidedly venerable, and the vaults possess the peculiar property of preserving the bodies entrusted to them in a perfect state, resembling in this respect the Egyptian mummy-pits. Dryness, one great essential to the preserving of animal matter, is complete here. But at one time, owing, it is said, to the nightly visits of a rascally sexton, for the purpose of stealing away the lead coffins from the dead, the damp night air entered and bade fair to play havoc with the mummies. There is a story told of his releasing from its coffin the body of a lady, who, however, looked him fiercely in the face with a pair of vengeful eyes, and so terrified him that he left his lantern and ran home half-dead with fright. The lady is said to have taken advantage of the light, and to have walked quietly to her own home, where for years afterward she lived a happy life! To many, Dublin will recall, first of all among its notables of the past, or at least only second to Dean Swift, the name of Edmund Burke. He was born in the Irish metropolis in 1729, when that city was at its flood-tide of prosperity, — when it was a centre of commerce, art, and oratory. His parents were of the plain people, and he himself, as he told his Grace of Bedford, “was opposed at every toll-gate, obliged to show a passport, and prove his title to the honour of being useful to Ireland.” Through this involved procedure, wherein his reputation as an agitator loomed quite as large as his powers of oratory, for sixty-seven long years he laboured at the business of state-craft; but, after all, he is best known to us for his labours in letters. Some one has said that “Rulers govern, but it is literature that enlightens,” and, concerning Burke, who shall not say that his writings and his speeches, which latter have come to be accepted as but another form of literary expression, were not even more productive of good than were his political agitations. To Americans Burke should be doubly endeared. He favoured American independence, though he was against the revolution in France. Richard Steele, though schooled at the Charterhouse in London, where he first met that other master of delicately phrased English, Addison, was born in Dublin in 1672 (d. 1729). Steele has been reviled as a “fashionable tippler, an awful spendthrift, and a creature of broken promises;” but it has remained for an American, Donald G. Mitchell, to glorify him as “An Irish dragoon, not a grand man or one of great influence, but so kindly by nature, and so gracious in speech and writing, that the world has not yet done pardoning and pitying.” It is in the latter aspect that Dublin is wont to think of Sir Richard Steele, — as the “Irish dragoon” of as many virtues as faults. It would be impossible to mention, even, the many celebrities whose names are identified with Dublin. Statecraft and letters alone number them in hundreds, and that great institution of learning, Trinity College, stands high among its kind. The site of Trinity College was previously occupied by an important monastery, suppressed by Henry VIII. The university was founded by Queen Elizabeth, and endowed with the monastic property and many very valuable private bequests. The college is Alma Mater to a long line of famous men, — Ussher, Congreve, Swift, Goldsmith, Burke, to mention but a very few. In the centre of the imposing front is the main gateway, flanked by the statues of Edmund Burke and Oliver Goldsmith. In days gone by, Donogh O’Brien, when driven from his titular sovereignty by his nephew Tarlagh, journeyed to Rome, taking with him his illustrious father’s crown and harp as gifts to the Pope. By some means or other, the harp — the once famous harp which had sounded through Tara’s halls — found its way back to Ireland, and is now, with the “Book of Kells,” the chief treasure of the library of Trinity College. The architectural splendour of Dublin is not very great, although certain of the chief buildings, other than the churches, are in many ways remarkable. Dublin Castle is a group of buildings covering ten acres of ground and dating from 1205, when a castle was erected for the defence of the city. Since the time of Queen Elizabeth it has been the official residence of the viceroy. The buildings are grouped around two courts, with a chief gateway on Cork Hill. The presence-chamber, ballroom (Hall of St. Patrick), portrait-chamber, and private drawing-room are handsome and historic apartments. The lower court contains the Bermingham Tower (formerly the state prison and now used as a depository for state records), the chapel royal, and the armory. The Bank of Ireland, formerly the Irish Parliament House, has a finely designed Ionic façade, with various adorning statues and escutcheons. The National Gallery of Ireland ranks among the world’s great collections of pictures, and is exceedingly rich in portraiture. Some one has said that there are but three truly great — in just what way the reader may judge for himself — business streets in the world. The first is the Rue de la Paix in Paris; the second, Princes Street in Edinburgh; and the Third, Sackville Street in Dublin. All will at once notice and admire its great width, its splendid dimensions, and its singularly attractive disposition of public and commercial buildings. The chief is the general post-office, with a fine portico and pediment bearing figures of Hibernia, Mercury, and Fidelity.

DUBLIN CASTLE. The little parish of Laracor, north of Dublin, came to Swift shortly after his return to Ireland as chaplain to Lord Berkeley. “Here he had a glebe and a horse, and became domesticated,” so far as it was possible for the man to be domesticated anywhere. Swift’s fluctuations between Ireland and London have been the subject of much comment and criticism. He had by no means settled down to the “jog-trot duties” of a small Irish vicar. Swift, the churchman, the litterateur, and the politician were much one and the same thing; and, in spite of his indiscretions, he did good service, though, to be sure, his sincerity was doubted. A story is told, of the occasion when he was urged for Bishop of Hereford, that the Archbishop of York stated to his queen “that inquiries should first be made as to whether the man is really a Christian.” He did not achieve the office, but was reconciled with the less influential deanery of St. Patrick’s at Dublin. Swift was born in Dublin at a house in Hoey’s Court, now (?) disappeared, in 1667. He died in 1745, and is buried, not among the literary giants at Westminster, but in St. Patrick’s at Dublin, the venue of his deanship. Swift as a satirist was unassailable in his time, and his literary reputation in general is without doubt — by reason of its versatility — greater than many a more prolific writer. The first announcement of this master, at once comic and caustic, was the “Tale of a Tub” and “The Battle of the Books,” when followed in rapid review various political and social tracts, the inimitable “Gulliver” (1727) and the “Polite Conversation.” “Cadenus and Vanessa” appeared without the author’s consent soon after the death of its heroine, Miss Hester Vanhomrigh, in 1723; but the “Diary to Stella,” the lady whom he afterward married, did not appear until long after the author’s death. Swift’s literary reputation — “at the head of the English prose-writers” — has been best summed up by his friend Pope in six short lines: “...Whatever title please thine ear,

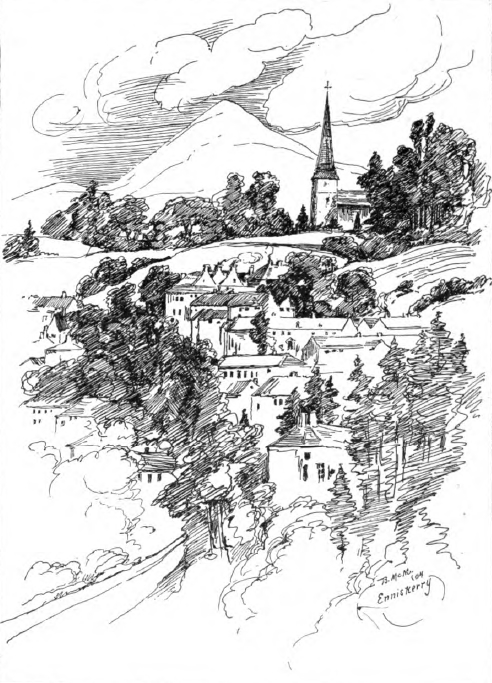

Dean, Drapier, Bickerstaff or Gulliver! Whether you choose Cervantes’ serious air, Or laugh and shake in Rabelais’ easy chair, Or praise the court, or magnify mankind, Or thy grieved country’s copper chains unbind.” As the river Liffey, which flows through Dublin, joins the Irish Sea, it expands into a noble bay, which is guarded on the one side by the Hill of Howth, and on the other by Killiney Hill, near Kingstown. Dublin has long been famous for the manufacture of poplin, dear to the hearts of the ladies. For many years the manufacture had declined, but a recent stimulus appears to have been given it. It was about the year 1780 that the trade first assumed a degree of importance in Dublin, though it had been introduced by the French Huguenots in the reign of William III. From that period till the Union in 1800, it had been gradually increasing in extent; but suddenly declined after the transference of the Irish Parliament to London; and Irishmen are fain to link the two events together as cause and effect. As the author has had occasion to say before, Ireland is not the saddened, sodden, blighted land that the calamity howlers and pessimists in general would have us believe. Certainly, in that beauteous country which lies immediately to the southward of Dublin, from Kingstown to Queenstown, there is no great evidence of sorrowing poverty; though, to be sure, there are in many parts no indications of great prosperity. There is a sort of happy mean in the lives of the Irish people; and, since the inhabitants of this particular region are domiciled in so lovely a spot, apparently they concern themselves little with regard to material wealth. From Dublin, south, is a veritable fairy-land of splendid hills and groves, the famous garden of the county of Wicklow. Bray is admittedly the best situated watering-place in the kingdom. But, more than all else, its chief importance lies in its position as the gateway to all the beauties of County Wicklow, whose residents go farther, and call it the Garden of Ireland. One may truthfully say of Wicklow, as of the other mountainous counties of Ireland, “the more one sees of it, the more one wants to see.” Its roads for the cyclist or the automobilist are, like the Irish character, a blend of the seducing and the bold, corrugated and rough in places, but withal fascinating and appealing, if only for their variety. Powerscourt, the Dargle, the Glen of the Downs, and the Devil’s Glen are the chief points of interest upon which one first comes from Dublin. The Dargle is a wooded glen of extreme beauty, three miles from Bray, from which a little mountain stream runs at the bottom of the gorge, quite hidden at times in a depth of wooded bank which must approximate three hundred feet. Powerscourt is beautiful enough, but it is more or less of the suburban order of attractiveness, lying as it does so near to Dublin. The waterfall at Powerscourt is the finest in Ireland. It pours down in a long, diagonal slope over a rocky precipice three hundred feet high. When George IV. came to Powerscourt, the whole fall had been dammed up on the cliff above, with the object of letting it loose when the royal party approached, so that a fine effect might be ensured. All this trouble and expense, however, was thrown away, as the “First Gentleman in Europe” lunched so liberally at Powerscourt House that he found himself unequal to the exertion of seeing anything of the demesne. The Dargle is rather of the conventional order of rivulet. It is not much of a stream at its fullest, but charmingly set in the woods, with mountain-tops rising over the trees, and some dainty waterfalls rather difficult to find. The four miles of road eastward to Bray are quite worth covering to see what the Dargle develops into near the coast; and, also, for the sake of the trim, rose-clad cottages, which here suggest none of that state of poverty we associate so recklessly with Ireland. One may see on the roadside notice-boards the intimation “These lands are poisoned,” and dogs, could they read, would be informed of danger to their persons. In Ireland they advertise in the papers that they are poisoning their lands “from this date,” and no dog has any remedy against the proprietors if he suffers in consequence of his illiteracy, or perhaps his meanness in not subscribing to that particular paper. The metropolis of the Dargle valley is Enniskerry, which sounds interesting, and proves upon acquaintance to be so, though there is nothing of great moment connected with its past or present. A few miles farther inland is Naas, the latter-day importance of which is based almost wholly upon its proximity to the race-track of the plain of Curragh and Punchestown. Naas is a delightfully quaint old town, its broad High Street being lined with little whitewashed houses, many of them tumbling down after long centuries of service. It has been narrated dolefully how Naas had once been the residence of the Kings of Leinster, but had now fallen from its high estate. From Naas to the Punchestown race-course is down a long and winding road through typical Irish scenery. The land along the roadside is dotted with little Irish cabins, with thatched roofs and whitewashed walls, and in the low doorways are gathered old grannies and swarms of little barelegged children. On race-days it is pretty to see these little dwellings, each with its piece of bunting tied to the chimney-stack.  ENNISKERRY. One may see also such sights as a chubby bareheaded boy with his arm affectionately around the neck of a fine fat pig; boy and animal equally interested in passers-by. It does not strike one as a genuine emotion, however; but, rather, as if it were got up for the occasion and for the delectation of the throngs who attend this most famous of all Irish race-meets. It is quite on a par with the flags and festoons which decorate Naas itself on these occasions, and the legends in old Celtic and English, which the cottagers en route display. “The top of the morning to ye,” “Come back to Erin,” “A hundred thousand blessings on ye,” and “A real Irish greeting” are, after all, too forced to pass current with visitors from across channel as genuine spontaneous emotion. On the occasion of the spring race-meeting at Punchestown, the little town of Naas is very animated. Inside the station-yard all the morning there is a mass of cabs and cars, which are taken by storm every time a train arrives from Dublin, and then with their load of passengers bump, smash, or blarney their way out. Music resounds everywhere. Even the local police have a band. This of course greatly facilitates the departure of the cars, for the horses of scores of them run away every time the band strikes up. The three miles of narrow country lanes between Naas and Punchestown are a flying procession of cars from eight o’clock till midday, most of them moving at a cheerful stretching gallop, while children and race-card-sellers run gaily in and out, and English or transatlantic visitors hold on for dear life, wondering when and where all this recklessness will end. The Wicklow mountains stand out in bold relief toward the east, and the clearness of the atmosphere ensures a magnificent view of a course which is situated in one of the finest bits of natural hunting country in the kingdom. The enclosures of Punchestown are very “select,” although a good deal of the riffraff is wont to assemble outside. The Irish police are extremely tolerant, and a thriving business is done in games of hazard, which have lately been ruthlessly extinguished at Epsom and Newmarket, in England. The roulette-table, the man with three cards, and his comrade with the thimble and the pea are among the recognized adjuncts of Punchestown. The country folk on the whole appear to enjoy the “sport,” and if, as is usually the case, the odds happen to be against them, they grin and bear it with naïve good humour. The bookmakers are a noisy, but, on the whole, an honest and withal humourous crowd, some offering to lay a starting price at “Newmarket, Stewmarket, or any old market, — starting price anywhere and everywhere,” while a rival will go so far as to declare: “We pay you whether you win or not.” On a recent occasion, when King Edward visited the Punchestown races in state, it was even a more brilliant event than usual. Here a great concourse of people awaited the arrival of the king and queen, and the grand stand was closely packed with a representative assembly of Irish aristocracy. The racing provided some very excellent sport. There were very full fields; and, when the horses got away, there was a splendid splash of colour, as the jockeys in all the tints of the rainbow streamed along the emerald course. The return from Punchestown on this occasion, as the writer has reason to remember, was far and away a wilder nightmare than any “Derby-day drive back to town” which could possibly be recalled. Imagine a solid, motionless block of cars nearly a mile long, with drivers, passengers, and police storming, threatening, and entreating, till at last a passage is slowly forced to the little wayside station at Naas. Here the railway officials had long ago given up the traffic problem in despair, and every train apparently got back to Dublin, or did not get back, by the unaided wit of the engine-driver. Yet one arrived at last, and a request to the officials for a full return of the killed and wounded was met with derision. From the newspaper accounts the next morning we learned that: “At a quarter to six, nearly half an hour late, the king and queen arrived in Dublin, and were met by all that was left of the population. They drove rapidly to the Viceregal Lodge, along roads crowded with cheering humanity, and looked very much pleased with their reception.” For ourselves, after this informal procedure, we had retired to our hotel to remove somewhat the stains of pleasure-making, — which are often as ineradicable as those of battle, — and, after the inevitable “meat tea” of the smaller hostelries throughout the British Isles, followed Mr. Pepys’s practice, “and so to bed.” Near Curragh is Monasterevan, with its ruined refuge-sanctuary, and Lea Castle. A prominent woody eminence is Spire Hill, beyond which are the picturesque ruins of Strongbow’s Castle on the isolated rock of Dunamase. Beyond is Maryborough and the plantations of Ballyfin, which clothe the feet of the Slievebloom mountains, and frame the flat bogland district. At Aghaboe, i. e., Ox-field House, stands the ancient abbey founded by St. Canice in the sixth century. Near the river Suir is a plain-fronted, square-towered edifice, known as Loughmore Castle, and a near-by ridge with a curious notched appearance has for its name Sliav Ailduin, — the Devil’s Bit Mountain. Here is Thurles, the scene of William Smith O’Brien’s capture. Here, also, Doctor Cullen summoned a Romish council in the mid-nineteenth century. Within three miles of Thurles is Holy Cross, where “the wearied O’Brien laid down at the feet of Death’s angel his cares and his crown.” “There sculpture her miracles lavished around,

Until stone spoke a worship diviner than sound; There from matins to midnight the censers were swaying, And from matins to midnight the people were praying; As a thousand Cistercians incessantly raised Hosannas round shrines that with jewelry blazed. While the palmer from Syria — the pilgrim from Spain — Brought their offerings alike to the far-honoured fane; And in time, when the wearied O’Brien laid down At the feet of Death’s angel his cares and his crown, Beside the high altar, a canopied tomb Shed above his remains its magnificent gloom; And in Holy Cross Abbey high masses were said, Through the lapse of long ages, for Donald the Red. O’er the porphyry shrine of the founder, all-riven, No lamps glimmer now but the cressets of heaven!” Simmons. Across the plain of Curragh is Kildare, i. e., Wood of Oaks, where St. Bridget founded a nunnery, in which the vestal sisterhood guarded the ever-burning fire, so beautifully and picturesquely alluded to by Moore: “Like

the bright lamp that shone in Kildare’s holy fane,

And burnt through long ages of darkness and storm, Is the heart that deep sorrows have frowned on in vain, Whose spirit outlives them, unfading and warm.” This convent of St. Bridget’s was founded in the fifth century, and its perpetual fire was kept burning until the Reformation. The house where it originally burned is still in evidence, and the cathedral castle and round tower (130 feet in height) form a triumvirate of venerable attractions for all. To the northward is the Hill of Allen, once crowned, it is said, with three royal residences belonging to the Kings of Leinster. Wicklow Gap, Glendalough, and the Seven Churches next command attention, as one journeys toward Wicklow town. Glendalough is thirty miles from Dublin, locally known — and perhaps more widely — as “The Valley of the Seven Churches.” It is the locale of the legend of St. Kevin and Kathleen. The antiquarians have evolved an elaborate thread of legend and tradition concerning the founder of an ancient seat of learning here, but most of them ultimately lost themselves in the intricacies of the web which they wove. Moore, with all his popular and sentimental methods, gave the story — though in this case he has tuned his lute with sadness — much more pleasantly and lucidly, when he told of St. Kevin, who, like St. Anthony, was tempted by the lovely Kathleen, herself so enamoured of him that she was willing even to “lie like a dog at his feet.”  GLENDALOUGH. These must have been trying times for St. Kevin, for, to continue Moore’s words, we learn that: “’Twas from Kathleen’s eyes he flew,

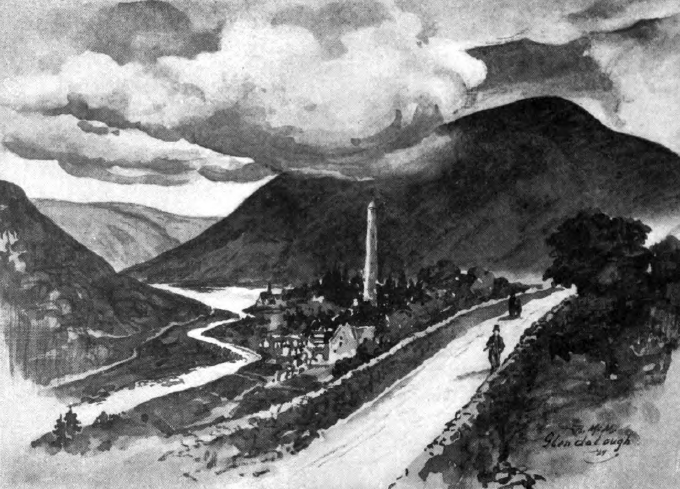

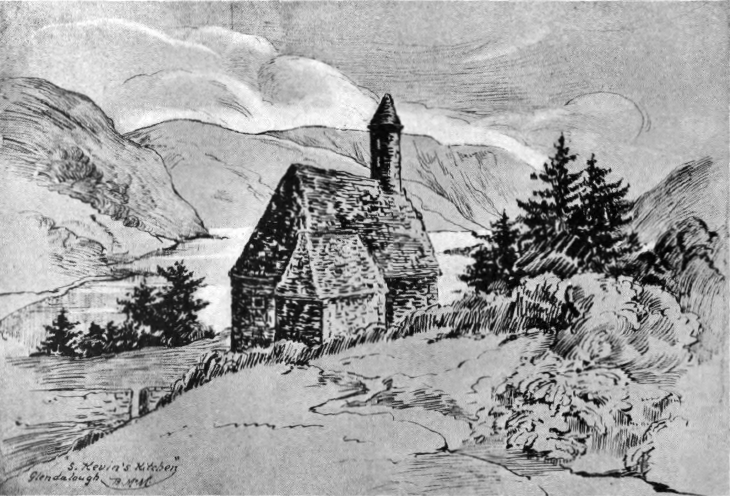

Eyes of most unholy blue! She had loved him well and long, Wished him hers, nor thought it wrong. Wheresoe’er the saint would fly, Still he heard her light foot nigh; East or west, where’er he turn’d, Still her eyes before him burned.” Thirteen hundred years ago, when England was still in a state of modified barbarism, Glendalough was of great importance. It was then that the famous churches, whose ruins still stand to-day, were built. Nearly a thousand years ago, Glendalough had her mansions; her treasure-houses, where the chieftains kept their stores of gold and silver, precious stones, and armour; her famous colleges, to which came students of high lineage from all Western Europe. It became known the world over as a place of sacred associations, great learning, and immense wealth. In the Dark Ages, there could be but one end to a city possessing the last advantage, especially as it was small and easy to besiege. After endless trouble from both Danes and English, the latter nation finally sacked and burned the place in 1398. Glendalough never really lifted up her head again, and is to-day but a hamlet of a few score of cottages. “Dracolatria” — the serpent worship of the Irish pagans — is supposed to have flourished here for ages before the founding of the Seven Churches by St. Kevin; and various legends and traditions, written and oral, are still current with reference to the practice.  ST. KEVIN’S KITCHEN. Glendalough will endear itself to all who have not hearts of stone. St. Kevin’s ruins are up and down the glen, and his hermit bed still stands in the dug out of the cliffs. That old, old cemetery of Reefert Church, with the thorn-bushes around it, is reckoned among the unique things in Ireland for its tomb of King O’Toole. The present cemetery, all about and within the ruins of the “cathedral,” is also characteristically Irish and charming. There is a monument here which bears the inscription: “We append a record, as far as obtainable, of clergymen buried in this church,” but has not a single name on it. Is this Irish humour, or is it an indication of Irish poverty? The “oldest inhabitant” could not tell the writer. Hosts of other dead are commemorated in stone, and, moss-covered, the headstones loll here at all angles, as do they elsewhere in Ireland. Just below is St. Kevin’s “kitchen,” with a tower like that of the broken, but still striking, round tower not far beyond. Formerly, it was one of the hermit’s churches (it was never a kitchen, in fact, and no one seems to be able to explain the nomenclature); but it has now been turned into a little museum of decidedly commonplace attractions. In the church, the “lady-church” of this group of churches, is the reputed burial-place of St. Kevin. As might be expected, no memorial exists of the holy man but the walls of this tiny church, if even they have genuinely survived his epoch, — the sixth and seventh centuries. No indications point to the exact resting-place of his bones, and the most that is known is that he died at Glendalough in 618 A. D. at the advanced age of 102. “And that is a doubtful fact,” says the local cicerone. Wicklow itself is a picturesque crescent-shaped coast town. Its name is borne by the Gap at Glendalough, the county, and that famous headland which juts out into St. George’s Channel, as only a few promontories do outside the school geographies.

THE VALE OF AVOCA. The ancient Irish called it Gill-Mantain; but, when it fell before the onrush of the Danes, its name was changed to Wykinlo. The chief architectural remains are those of a Franciscan friary of the reign of Henry III., and an Anglo-Norman castle completed in the fourteenth century. Between Wicklow and Arklow lies the celebrated Vale of Avoca. It has been made immortal by the poet Moore; but, though its fame is well deserved, and it is a spot beloved by all who have ever seen it, it is in reality no more beautiful than other similar spots elsewhere. The Vale of Avoca shares with Killarney, Blarney Castle, and the Giant’s Causeway a popularity which is not equalled by any other of the beauties of Ireland. Here “in this most pleasant vale,” where the Avonbeg joins the Avonmore, is the “Meeting of the Waters.” Moore lavished his choicest phraseology upon its charms; and tourists — since there have been tourists — have devotedly stood by, book in hand, and attempted to fit in the poet’s words with each tree and stone and rivulet. For the most part they have not been successful; and the words the poet sung — “There is not in the wide world a valley so sweet

As the vale in whose bosom the bright waters meet. Oh! the last rays of feeling and life must depart, Ere the bloom of that valley shall fade from my heart. . . . . . . . . . . “Sweet vale of Avoca! how calm could I rest In thy bosom of shade with the friends I love best, Where the storms that we feel in this cold world should cease And our hearts, like the waters, be mingled in peace" — might quite as readily have applied to any other

spot as fair.

It will never do to disparage Moore’s poetry, and least of all in a chronicle of Irish experiences; but, once and again, an idol does really shatter itself, or at least totters unsteadily on its base; and when one has made the round of all Ireland’s fairest beauties, and heard Moore’s melodies dinned into his ears by importunate touts and mendicants without number, the sentiment is apt to grow thin, and sooner or later the soul rebels. At this point, then, the author’s patience gave out, and so he records his mood, however unseemly it may otherwise appear. It is indeed a pretty valley, strangely pretty, if you like; and one can hardly remain unmoved and unemotional before its expanse of green, its oaks and beeches, its rocks and rills, its ivies, and more than all else its sunsets. But when one has said with Prince Puckler Muskau — that much-quoted royal German so useful to makers of guide-books — that it is all “exquisitely beautiful,” one has said the first and the last word on the subject. It should be visited and seen in all its beauties; but the experience will not awaken in the hearts of many the emotions which we may presume Moore felt.  THE MEETING OF THE WATERS. Near by is Avondale, the former home of Charles Stewart Parnell. Where the Avonbeg unites with the Avonmore is formed “The Meeting of the Waters.” Many painters have limned its beauties; and, like Killarney, Loch Katrine, and Richmond Vale, on the Thames, replicas of its charms used years ago to find their way in the “table books of art” and “Treasuries,” with which our parents and grandparents used to decorate a small table set before the front window of the parlour. The part played by the Norman invasion of Ireland has been neglected and overlooked by many in favour of that more portentous invasion of England. In Ireland the Normans first landed in a little creek on Bannon Bay on the Wexford coast. The advance-guard was composed of thirty knights, sixty men in armour, and three hundred foot-soldiery, under Robert Fitzstephen. This brought on the siege of Wexford, of which the annals, as well as the many remains of ruined castles and churches founded by the invaders, tell. All this ancient history pales, in the minds of the native bar-parlour frequenters one meets in these parts, before the more vivid, or at least more readily recollected “little affair” of Vinegar Hill and “the Men of ’98,” the site of which, with Enniscorthy, lies just to the northward. A half-century ago historians wrote of this as a “matter yet fresh in the memory of living men,” and the great rebellion — so great at least to Ireland — has been dealt with by writers of all shades of opinion ad infinitum. Even the music-hall songs have perpetuated the belligerent aspect of the inhabitants of Enniscorthy, to say nothing of Killaloe. Nevertheless, the incident of the Norman invasion of Ireland, and the parts played therein by Fitzgerald, Diarmid, the traitorous M’Murrogh, Roderick, Strongbow the Dane, and Prendergast, — named in Irish history as “the faithful Norman,” — presents an inextricable tangle of creeds and races which requires a singularly astute historian to place in line. It is now seven hundred years since the name of Prendergast was linked with honour and chivalry in Ireland; but something of his earnestness and spirit still lives amongst those who bear his name, if we may judge from the tenor of a modern work by one Prendergast, entitled “The Cromwellian Settlement of Ireland.” Aubrey de Vere, in his “Lyrical Chronicle of Ireland,” has emblazoned Prendergast’s valour in verse: THE FAITHFUL NORMAN “Praise to the valiant and

faithful foe! Give us noble foes, not the friend who lies! We dread the drugged cup, not the open blow: We dread the old hate in the new disguise. “To Ossory’s king they had

pledged their word.

He stood in their camp, and their pledge they broke; Then Maurice the Norman upraised his sword; The cross on its hilt he kiss’d, and spoke: “‘So long as this sword or this arm hath might, I swear by the cross which is lord of all, By the faith and honour of noble and knight, Who touches you, prince, by this hand shall fall!’ “So side by side through the throng they pass’d; And Eire gave praise to the just and true. Brave foe! the past truth heals at last: There is room in the great heart of Eire for you!” Round the coast from Wexford to Waterford one passes the famous Tuskar lighthouse, which, with the Saltee light-vessel, thirty miles to the southward, and Carnsore Point, which lies between, forms the turning-point — or the corner which must be rounded — of the vast sea-borne traffic bound up the St. George’s Channel from the Atlantic. The chief historical monument of Waterford, with the exception of the reconstructed castle and Ballinakil House, the last halting-place of the fleeing Stuart king, is a squat circular building known as “Reginald’s Tower.” It sits close to the quayside, and is by far the most notable landmark, viewed from either sea or land, which the city possesses. Its erection is credited to Reginald, the Dane, some nine hundred and odd years ago. Kingsley, in “Hereward the Wake,” weaves much of romance around its sturdy walls.  Reginald’s Tower: Waterford In 1171, when Strongbow and Raymond le Gros took Waterford, it was inhabited by Danes, who, with the exception of the prince of the Danes and a few others, were put to death. It was here that Earl Strongbow was married to Eva, daughter of the King of Leinster; and here, too, that Henry II. first landed in Ireland to take possession of the country which had been granted to him by the bull of Pope Adrian. Near Waterford is Dungarvan, once a fishing-town of considerable importance. Its fishermen were bold, and went far out to sea, for it was a Dungarvan man who was captured and made to act as pilot by the corsairs of Algiers, who sacked the town of Baltimore, close to Cape Clear, in 1631, when all the inhabitants were killed or carried off into slavery. A curious page of the Irish history, and one which reads more like romantic legend than fact. This man’s name was Hackett, and the story tells that his service to the Algerians was repaid, by his outraged countrymen, with the halter. Between Cork — with its poetic associations of the Shandon Bells, the river Lee, and of Blarney Castle — and the glens and vales of Wicklow, there is no spot to equal in picturesqueness and romantic environment the celebrated valley of the Blackwater, which, forming a broad estuary, mingles with the waters of the Atlantic at Youghal Harbour. The great beauties of the Blackwater only unfold themselves as one ascends the stream some twenty miles above Youghal, but the whole lower river has a placid charm which is quite inexplicable. For what is Youghal famous, say the untravelled? In matters Irish, for many things, but the most lively interest is awakened by the recollection of Myrtle Grove, the one-time residence of Sir Walter Raleigh, Governor of the Virginia Colony in the New World, who, though he had never been there, is popularly supposed to have introduced its tobacco into Great Britain. As a matter of fact, he did not, but some one of his understudies did; and it was at Myrtle Grove that his servant sought to save him from incineration by deluging him with water while he was smoking his favourite pipe. There is doubtless somewhat of legend about this; and the incident has been worn threadbare in its use by an enterprising firm of tobacco manufacturers; but, since Myrtle Grove really exists, and Raleigh really lived there, there is some excuse for it.  SIR WALTER RALEIGH’S COTTAGE, YOUGHAL. It was here, too that the potato, since become a too staple article of diet, was first introduced to Irish soil. Truly Raleigh is entitled to a reputation as a true benefactor of the race exceeding that due to his reputed chivalry to Queen Elizabeth. Without potatoes and tobacco, what might not have happened to the British race long before now? |